As a Bates trustee for nearly three decades, I attended Commencement whenever I could. It was my joy and my honor.

In most years, I marched with my fellow trustees, honorary degree recipients, the president, and other members of the platform party, joining them on the terrace of Coram Library as the Bates faculty took their seats on the Historic Quad, followed by the graduating class.

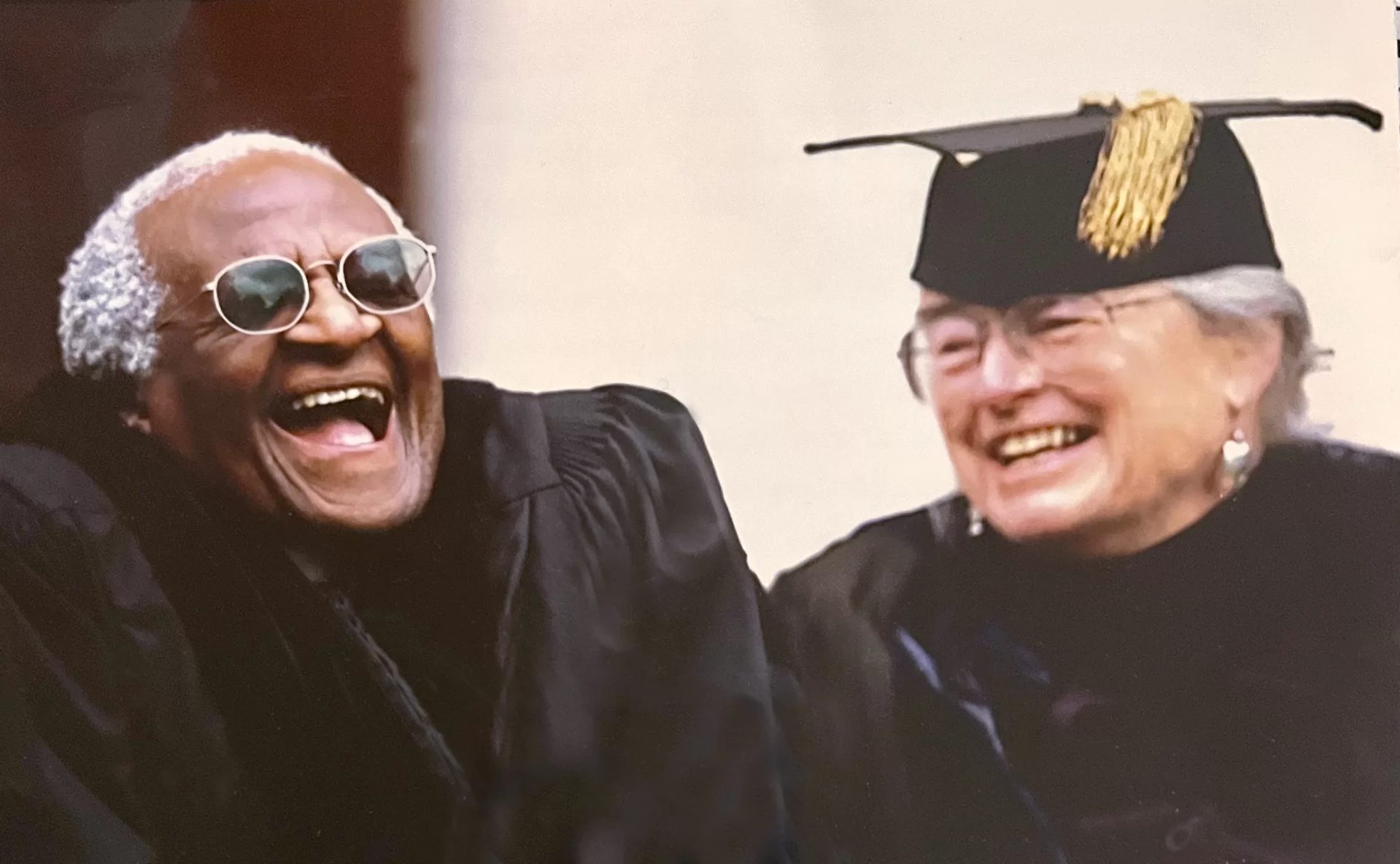

But on May 29, 2000, the college’s 134th Commencement, I did not march, as I was recovering from a back operation. Also recovering his good health was one of the honorands, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, that year’s Commencement speaker, who had undergone cancer surgery the prior fall.

Instead of marching, we rode a golf cart to the Quad, where we sat next to each other in Bates chairs on the Coram Terrace. From that perch, we watched the academic parade — and talked, a conversation that I will never forget, and recall often, particularly after hearing of Archbishop Tutu’s death on Dec. 26.

My first question to Archbishop Tutu was about his dreams when he graduated from the University of South Africa in 1955. His answer was that he wanted to become a medical doctor. But he realized that the apartheid system of government in South Africa would not allow him to go to England with that goal in mind so he declared he wanted to be a church rector.

With that goal, he was allowed to go study religion in England and thus his future path was set. He was ordained as a minister in 1961 and ultimately became archbishop of Cape Town, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his outspoken anti-apartheid leadership.

“There is no peace in southern Africa,” he said in receiving the Nobel prize. “There can be no real peace and security until there be first justice enjoyed by all the inhabitants of that beautiful land.”

There, he would reconnect and renew his deeply held convictions to make the world a compassionate and safe place for all humans.

When apartheid ended in the early 1990s, President Nelson Mandela named Archbishop Tutu as chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. So different from the Nürnberg trials after World War II, the commission was seen as a successful way of dealing with human-rights violations after political change.

The TRC took the testimony of approximately 21,000 victims, 2,000 at public hearings. In one session, in 1996, Tutu broke down in tears as he listend to the harrowing testimony by relatives of four leading Black civil rights activists who were abducted and murdered in 1985.

As the Bates academic procession continued to fill the seats in front of us, I asked Archbishop Tutu how he managed to stay positive listening to so many victims.

He explained to me that, to be renewed, he withdrew from all contact with people for one day each month and one week each year. During this week, he was often invited to a monastery, where he would receive food left at the door. There, he would reconnect and renew his deeply held convictions to make the world a compassionate and safe place for all humans.

It was a magical conversation. Then, it was time for Archbishop Tutu to give his address. He praised college students around the country for their fight against aparteid. “Those young people in those days, with the help of others, helped to change the moral climate in this country,” he said.

He called on everyone to imagine and participate in creating a better world. “Dream,” he told the graduates. “Dream of a new kind of world. Dream that it is possible to have a new kind of society where people matter more than things, more than profit.”

Then and now, Bates has identified and celebrated many wonderful honorands who continue Bates’ deep commitment to following a moral compass toward the compassionate world that Archbishop Desmond Tutu believed was for all.

M. Patricia Morse ’60 is a retired professor of biology at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories. She served as a Bates trustee from 1971 to 1976, and from 1978 to 2009. She lives in Friday Harbor, Wash.