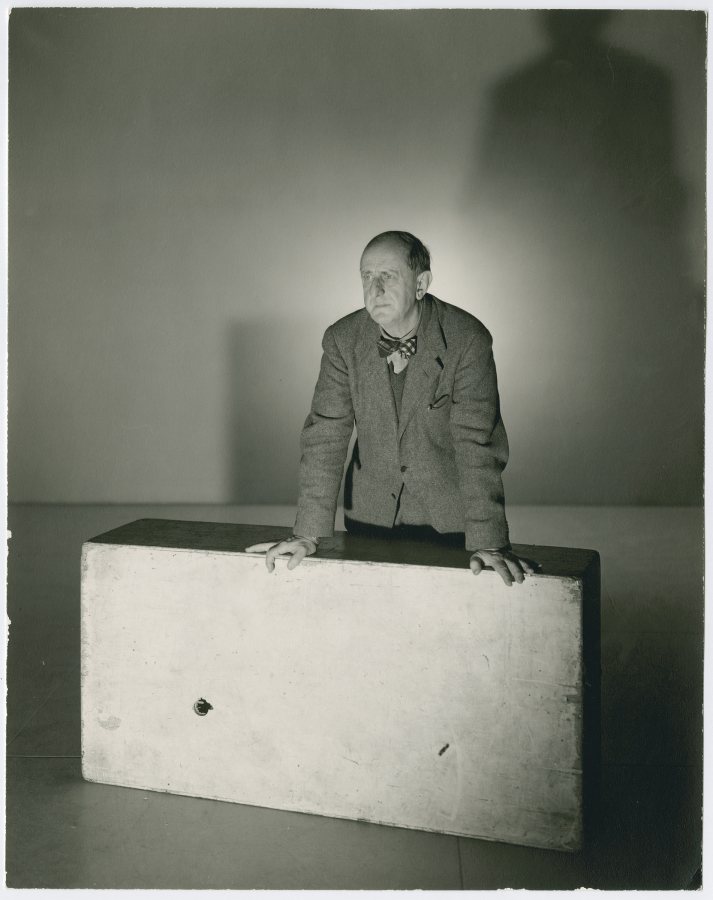

Lewiston-born artist Marsden Hartley never owned a home and had few material goods. But when he died 79 years ago, he left the world a wealth of canvases and works on paper. In part because he was so prolific and not yet a highly coveted name within the art world at the time of his death, there are still some tantalizing mysteries about the locations and ownership of some of his art.

For years, Gail R. Scott, an independent art historian and preeminent authority on Hartley, has been working with the Bates Museum of Art on various Marsden Hartley–related projects. The Marsden Hartley Legacy Project: The Complete Paintings and Works on Paper was launched in 2019. This collaborative project seeks to solve those mysteries and build a definitive online catalog of Hartley’s works. The enormous task of locating and documenting more than 1,600 works by Hartley is well underway but it has just won the generous support of a family foundation with a rich history of collecting works by Hartley.

The New York–based Vilcek Foundation, which partnered with the Bates College Museum of Art for the extraordinary 2021 exhibition Marsden Hartley: Adventurer in the Arts, has announced a $100,000 gift to support the ongoing Marsden Hartley Legacy project.

“We are thrilled to continue our partnership with the Bates College Museum of Art,” says Rick Kinsel, president of the Vilcek Foundation. “This digital publication of his complete body of work will revolutionize Hartley scholarship by providing the public with access to Gail Scott’s incredible research.”

The Bates Museum of Art houses many of Hartley’s personal possessions, including paintings, letters, photographs, and treasured mementos from his extensive travels, gifted to the college by his heirs beginning in 1951. His niece Norma Berger was his closest relative and in 1955 she made an additional gift to the college that included several early oil sketches and 99 drawings. The drawings represent the largest group of Hartley’s work in this medium and includes studies for some of the artist’s well-known paintings.

Hartley always considered himself a Maine artist, and in his lifetime, he expressed a wish that a memorial collection be established in his hometown, “for the boys and girls of Maine.” Berger thought it fitting that a Maine college house these collections.

“The Bates College Museum of Art is an amazing resource for Hartley scholarship due to the extensive breadth of the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection,” says Emily Schuchardt Navratil, curator at the Vilcek Foundation. (Navratil’s lecture at the museum, “Adventure in the Archives,” was recorded and is available on the museum’s website.)

“It’s just a huge boost,” says Scott of the Vilcek grant. As rewarding as the work is, documenting the hundreds of Hartley works in the database is laborious, including finding “all the minute details of ownership, gathering images, and documenting the history of each painting, the exhibitions it was in, and the articles and books that have been written about each work.”

With the Vilcek Foundation’s financial support, Scott will be able to hire another researcher and work with a social media manager to start sharing some of the considerable work the project has already accomplished and raise awareness of its intent.

Tracking down all the Hartleys takes detective work. Consider the case of the works entitled Trees. There are 25 Hartley works on paper and canvas with that title. Any mention of a Trees in records of exhibitions or media clippings that doesn’t include an image or specific dating just adds to the confusion. “You have to figure out which one it is,” Scott says.

Hartley’s papers are in the Archives of American Art (within the Smithsonian) and have now been digitized, which makes some of Scott’s detective and cataloging work easier. And the work of a midcentury researcher, Elizabeth McCausland, has proven to be invaluable, Scott says. McCausland corresponded with Hartley before his death and started a catalogue raisonne of his work. In 1952, McCausland published a book, Marsden Hartley. She died in 1965, the work unfinished. “I’m standing on her shoulders,” Scott says.

“The trouble is, now I can’t find the current owner.”

“The most important part of this research,” Scott says, is the provenance, the tracing of ownership from the current owner back to the artist. It’s challenging work. A case in point unfolded last summer when Scott visited with family members in the coastal Maine town of Corea, where Hartley lived and worked in a modest studio during his last years.

The family had received a painting of his called Beaver Lake. It depicted a landscape in New Hampshire. When Scott got in touch with their granddaughter, she recalled that the family was grateful for the gift, but, she told Scott, “it didn’t exactly have a place of honor in their house because Hartley’s reputation was not fully understood.” It ended up in a closet. The family eventually decided to sell the painting and brought it to a gallery, where it was sold. Scott had an image of a painting that fit the description and showed it to the granddaughter. “She said, ‘Oh yes, that is it,’” Scott says. “The trouble is, now I can’t find the current owner.”

There are a number of Hartleys like this, known to exist — through photographs or other documentation — but unseen for years. “There are a lot of what I call ‘whereabouts unknown’ pieces,” Scott says.

Have a Hartley?

The Hartley Legacy Project invites people who believe they own a Hartley to submit information to Gail Scott and her colleagues. One can review this statement on the policy guidelines on image size and security. Send submissions and questions to hartleylegacy@bates.edu.

Scott and her colleagues invite people who believe they own a Hartley to submit information to the legacy project, “to pull out some folks who do have genuine Hartleys,” Scott says. “Some have appeared.”

One of the few that have been identified as real is a 1936 painting called Friend Against the Wind that was recently located in a bank vault in Portland, where its owner had placed it many years ago. The last time it was seen publicly was in 1980, when it was shown at Portland’s Barridoff Galleries, but Scott knew of its existence from a description and an image in a catalog from a 1987 exhibition in Nova Scotia that mentioned it. After the Portland Press Herald reported the painting’s rediscovery in early January, media outlets around the country picked up the story, with coverage appearing in Newsweek, ABC News, the San Diego Tribune, and Art News, among other publications.

The interest generated by that single discovery is a demonstration of the need for the legacy project, says Dan Mills, director of the Bates Museum of Art. “This initiative is timely, and there is urgency in its completion. Of the American artists of his stature and generation, Hartley is one of the very few without a publication of his complete body of work.”

“We’re grateful to the Vilcek Foundation for its recognition of the importance of our work,” Mills says.

Scott leads a group that includes research assistants, digital cultural content specialists, and staff from Bates Information and Library Services and Bates College Museum of Art. In the past, Hartley scholarship, including the legacy project, has been supported by funding from a number of foundations, including the National Endowment for the Humanities (2010), the Henry R. Luce Foundation (2016), the Coby Foundation (2017), and The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts (2018, 2019).

“He had even less money than usual,” Scott says. So, “he burned about 100 works. Destroyed them.”

The museum and Scott share the goal to find every existing Hartley work if possible. He was prolific. At the time of Hartley’s death at 66, he had many works stashed in a warehouse in New York. Scott says he’d accumulated a great deal of his own work over the course of his career for a simple reason: “They didn’t sell. Ever since the very start of his career, when he was with Alfred Steiglitz [representing and showing his work], maybe one or two of the 15 paintings and drawings he was showing would sell. The rest the gallery had to store.”

Around 1935, Hartley was told he had to pay something toward the storage bill. “He had even less money than usual,” Scott says. So, “he burned about 100 works. Destroyed them.”

It’s a painful thought. “Lord knows what they were,” she adds. “Hopefully his eye culled what was less important, but it is not known.”

Hartley died without a will and it took more than two decades after his death for the paintings to be sold off and the estate to be settled.

Collectors Jan and Marica Vilcek began acquiring Hartley works early in their collecting days and now own 22 of them, many of which were part of the Adventurer in the Arts exhibition, which closed at Bates in November 2021 and will open in New York this September, with Bates contributing artwork as well as a selection of his personal effects.