What does Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake have to do with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Why did Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy decide to stay in Kyiv? And how are Zelenskyy and Russian president Vladimir Putin controlling the narrative, each in their own way?

From a recent campus discussion among four Bates faculty members with wide-ranging expertise in the issues at play in the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, here are 10 takeaways.

The narrative isn’t new

One of Putin’s biggest defenses of his invasion of Ukraine is that the current Ukrainian governing body is, in fact, illegitimate.

In 2014, during the Revolution of Dignity, Viktor Yanukovych, then president of Ukraine, declined to sign a political association and free trade agreement with the European Union, instead choosing to strengthen ties with Russia.

Ukrainians disagreed with this decision, and the Ukrainian parliament unanimously voted to remove Yanukovych as president, resulting in him fleeing the country, fearing retaliation. Putin’s perspective is that the government that replaced Yanukovych is illegitimate, and he uses this to back his claim that the invasion intends to “free” Ukrainians from their oppressors.

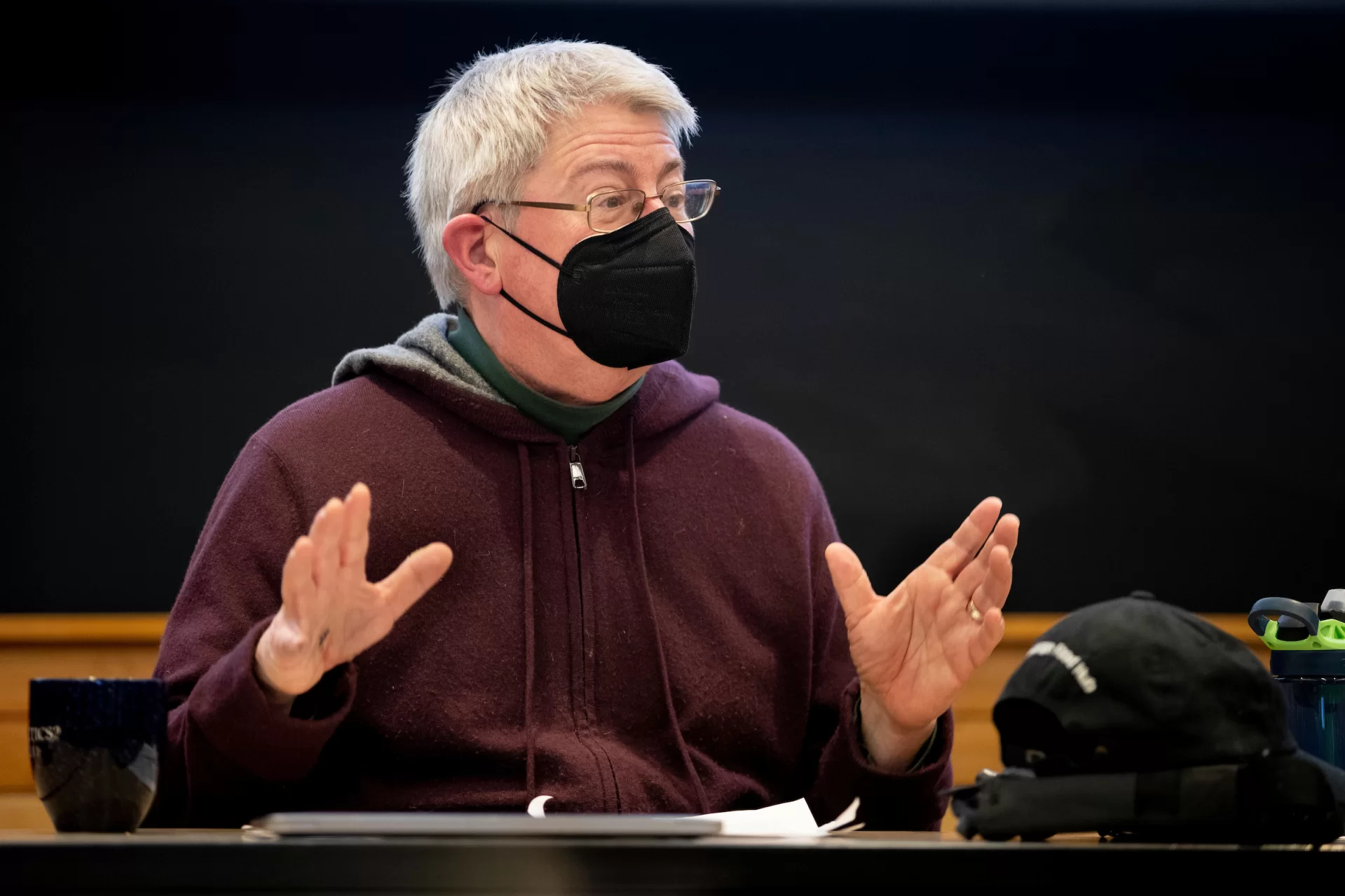

“From the top of the Russian government down, it’s a pollution of nationalists and neo-Nazis who have, as their goal, the erasure of Ukraine’s true history, in which Ukraine returns to its appropriate place, as part of Russia,” said Professor Emeritus of Russian Dennis Browne during Wednesday’s discussion, sponsored by the Department of German and Russian Studies and by the Program in European Studies.

“This is what I would call the pollution of Ukrainian extremist arguments. I don’t see any off ramp on either side of this today.”

Ukraine is no ‘border zone’

Putin claims Ukraine is a “brother” to Russia, part of its own civilization.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy has tried hard to redefine Ukraine’s identity, starting with associating it in the world’s eyes as part of Europe (including formally seeking membership in the European Union, which experts say would take months if not years).

Zelenskyy is trying to inspire empathy and a sense of camaraderie with the rest of Europe.

“One of the things that was immediately apparent at the very beginning of this crisis was that there was what we might call a PR crisis, where essentially the world hadn’t thought about Ukraine since 2014,” says Cheryl Stephenson, lecturer in Russian.

The public relations crisis is that the rest of Europe — and the U.S. — understands Ukraine as “a kind of a seam or a border land,” says Stephenson.

Ukraine exists “between the concept of Europe and the concept of Russia, between concepts like East and West, democracy and authoritarianism, civilized, and uncivilized are words that are being used a lot right now.”

‘On-the-fly mythmaking’

Zelenskyy seeks to change the concept of Ukraine as a buffer zone between Russia and the rest of Europe.

Instead, Zelenskyy wants the rest of the world to see Ukraine as a seam, where Russia isn’t almost invading Europe; it is invading Europe. Which makes Putin’s threat to Ukraine a threat to the rest of Europe.

So how is Zelenskyy attempting to re-identify Ukraine and give the rest of the world a reason to help?

Zelenskyy’s decision to stay in Kyiv and his constant updates and videos are not only to boost morale, says Stephenson, but they also serve as a way to transform national and international narratives about Ukraine.

“[It’s a] kind of on-the-fly mythmaking, and like all kinds of myth, myths that surround nations are powerful regardless of their truth value,” says Stephenson.

“Their power is connected to the kind of emotions that they invoke in people, both about others and about the self. And that’s very actively going on in these very brief social media interactions between the Ukrainian government, and between international audiences and the people of Ukraine.”

Various social media accounts for the Ukrainian government have begun to be regularly translated for international audiences while other people are translating memes and messages that promote Ukrainian culture and values, and this all helps boost Zelenskyy’s narrative, says Stephenson.

Sphere of influence = right to interfere?

Putin sees Russia’s sphere of influence as international, so he believes he has the right to interfere in Ukraine and, specifically, to interfere in their government. This isn’t a new idea, nor is it unique to Putin.

Referring to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Professor of Politics Jim Richter noted that “this is the second time in this young century that a great power has invaded a country of over 40 million people without provocation and in violation of international law.”

And in both cases, said Richter, who chairs the Program in European Studies, “the population of that great power — and possibly the decision-makers as well — were under the impression, perhaps delusionally, that the local population would celebrate the invaders as liberators and greet them with flowers and celebrations.

“Most people now agree that the invasion of Iraq, regardless of its moral implications, was a complete and massive strategic blunder.”

Wary and weary of war

“Russians, I think, are generally averse to war. They accept it when necessary,” said Richter. “Russians have a knowledge of war that people in the U.S. do not. They get the stories from their grandparents. It’s still a living memory, the absolute horrors of war — but also the necessity of war in certain times.”

Putin believes that the way to convince Russians of the necessity of war is to control the narrative, using his rhetoric to unify their beliefs and identity as Russians.

“I think Putin hoped he could control the narrative enough,” Richter said. “But with the resistance of Ukrainians, the length of time in the war, the costs and the economy, the resistance likely to grow, the harsher repression that’s going to happen in Russia, that’s going to be more and more difficult to maintain.”

Echo, echo

Putin has surrounded himself with people who agree with him, creating an echo chamber that rings with his own voice.

That’s caused problems in Putin’s strategy, says Richter, and led to his underestimating the determination of Ukrainians to fight and underestimating the willingness of many other countries to defend Ukraine against Russia.

From accepting Ukrainians fleeing their besieged homes, to offering food and medical supplies, to volunteering to fight alongside Ukrainian soldiers, much of the rest of the world has taken a stand with Ukraine.

But underestimation isn’t Putin’s only problem, says Richter. He’s also overestimated his own military, and the willingness of Russians to support his decision to invade Ukraine.

While some polls show high Russian support of Putin’s decision, those polls are being released at a time when Putin is tightly holding the reins of information circulating within and coming out of Russia.

‘There is no war in Ba Sing Se’

On March 4, Putin signed a new law against the spread of “false information” about Russian armed forces. Punishable by up to 15 years in prison, “false information” includes using the term “war” to refer to what’s happening in Ukraine; instead, Putin says, it’s a “special military operation.”

Other taboo words include “invasion,” and using “Nazi” and “Hitler” to refer to Putin. Encouraged words are “demilitarize” and “de-Nazify” in reference to Putin’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. Enemies are “foreign agents.”

It’s right out of the animated series Avatar: The Last Airbender, where citizens are forced to repeat the phrase “there is no war in Ba Sing Se,” the mythical city-state, until they are brainwashed.

Of course, the result has been widespread and creative wordplay, as Russian media and citizens circumvent the new law, from using antonyms to deliver an easily-deciphered message, to creating memes to lift spirits.

Lecturer in Russian Marina Filipovic gives the example of a meme in which the cover of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace has been doctored to read Special Military Operation and Peace.

“It became viral. People are sharing it, reading it, and this wordplay brings comical relief in these distrustful times,” says Filipovic. Through the meme, “they can speak.”

Access to news

While Putin is blocking access to and banning media outlets and social media platforms, Filipovic described how Russians are still finding ways to communicate with each other and share resources.

They’re using apps instead of browsers to access social media, sharing and signing petitions condemning Putin’s war, and circumventing the ban on Facebook (which Filipovic said only 7 percent of Russians use) with the more popular Russian messaging and social media platform, Telegram, and social media platform V Kontakte.

But blocking Facebook could just be a sign of what’s to come, says Filipovic.

“By limiting access to Facebook, what the government wants to signal is what may happen to the actual Russian equivalent, VK, if certain censored things are being promoted.”

Swan song

On March 1, Russia’s last independent TV news station, TV Rain, was blocked by Putin, but not before they delivered one final, poignant message, broadcasting a video of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

There was a message in that medium: In 1991, during the failed Soviet coup d’état that tried to take down Mikhail Gorbachev, the government played a video of Swan Lake on TV stations for three days to block information from being delivered.

“Playing this in the moment as they’re leaving the TV station is a high level symbolic gesture,” says Filipovic.

Outcome unknown, expansion unlikely

Richter said the possibility of Putin expanding his war into the rest of Europe is unlikely.

“I think there is something in Russian military doctrine that says, ‘Escalate to de-escalate.’ Putin is still going to be pushing. He’s still got other things to do on the ground before he would go that far. I think it’s going to be really brutal, but I don’t think he’s going to expand at this point. I think he knows that that would be too dangerous.”

Still, “it’s going to be a long stretch,” said Browne.

Questions about how long Russia’s military will be able to continue attacking Ukraine can’t be easily answered. Nor can the question of nuclear warfare.

“The thing that worries me are the nuclear power plants and the reactors — not so much being hit by weapons, but the staff under pressure constantly,” says Browne.

“You don’t just go, ‘Well, we’re having a war, so let’s turn the plant off.’ It has to be done by experts, engineers who know what they’re doing. And I’ll be honest, one of my biggest fears is some kind of a leak that just comes from maintenance issues.”

Want more?

The panelists each shared their go-to sources for news about Russia and Ukraine:

- Filipovic recommends reading Masha Gessen, a journalist for the New Yorker and author of a book about Putin, The Man Without a Face.

- Stephenson recommends reading Faith Hillis and Kimberly St. Julian Varnon, both historians and writers, and the book The Gates of Europe, by historian and writer Serhii Plokhy.

- Richter recommends reading The Guardian.

- Browne recommends reading Open Democracy and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe