When I arrived with the Class of 1972 at Bates, in 1968, we were still performing rituals from the 1950s. At Orientation, we played the shoe toss and Pass the Orange. We wore Bates beanies and stood on Bobcat Den tables to sing the school song. We admired Roger Bill upperclassmen who unabashedly, eagerly even, went by names like Mental and Limp.

Everyone experiences college differently, and for me there were at least two distinct versions of Bates — the before times, and then the more chaotic, Age of Aquarius, place it became.

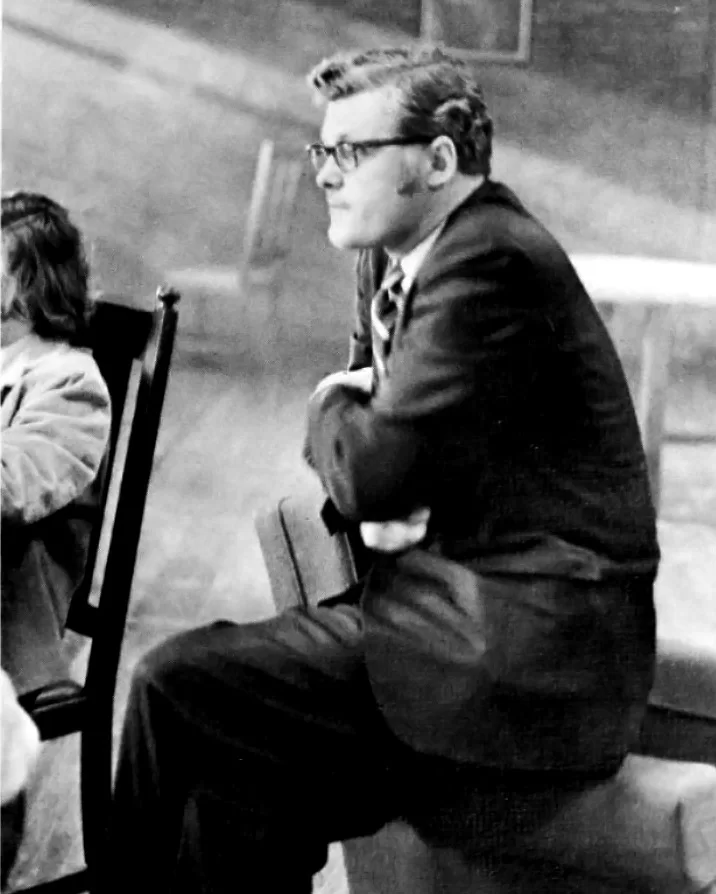

And for a few of us, the portal from one Bates to the other was provided by Garvey MacLean ’57, an assistant professor of religion. He led one of the first off-campus Short Term courses, “Religion in the Secular City,” or as MacLean preferred to call it, “Love in Action,” which took us to East Harlem in the spring of 1970 and took that chaos and inflected it with an enduring purpose.

In the beginning, we drank Budweiser and rotgut Grenache rose wine every Friday night, then rolled out of bed for 8 a.m. Saturday classes. Parietal hours kept men and women separate except for forays into the downstairs lounge or rare trips into dorm rooms. Women still had posture pictures, and remnants of the 19th century seemed to linger in every dusty corner of the Gray Cage.

Marie, our housekeeper, showed up every Monday morning to clean the boys’ rooms and remake our beds with clean sheets. She overlooked cigarette burns on the couch and picked up leftover beer cans while holding her nose then clucked her disapproval at us. No maids set foot in the girls’ dorms on the assumption that young ladies should take care of it themselves.

Bates seemed to offer a predestined commuter train ride from the Quad to Suburbia. But then 1969 hit, a tsunami blasting down College Street, washing away men’s crewcuts and the bottom half of the women’s skirts, along with the rest of that first, 1950s-influenced Bates. The Revolution had arrived in Lewiston. We traded in six packs of beer for nickel bags of dope. Men wore hair long enough to put up in braids, sported beards and mustaches, and started every sentence with “Hey man” and finished with “Far out, dude.” Women had hair down their backs like Joni Mitchell, didn’t care about marriage, and had already joined the sexual revolution.

On March 26,1969, William Baird brought his one-man crusade to legalize abortion to campus, handing out photographs of dead or mutilated women. Bearded Quakers from the American Friends Service Committee sat in the upstairs lounge of Chase Hall handing out pamphlets about legal rights of draftees and applications to become a conscientious objector. Returning veterans and new students spoke of a war that didn’t square with the sanguine propaganda coming out of the Johnson administration.

That fall — 1969 — speakers like Yippie co-founder Paul Krassner came to campus and talked about class warfare, Jimi Hendrix’ penis, the military-industrial complex, and how to join the radical underground. On Moratorium Day protests in October 1969, John Shages ’70, dressed like Uncle Sam, led us back and forth in downtown Lewiston as we shouted obscenities about President Nixon and raised our fists: “Hell no! We won’t go!”

(Fletcher/Lewiston Evening Journal)

That December, the first military draft lottery since 1940 took place. Before the lottery, the oldest eligible men were drafted first. Nixon hoped a lottery would reduce anti-war sentiment on college campuses by making it seem “fairer.” But we would have none of that.

A few weeks after the lottery, sophomores Mark Winne, Fred Wolffe, Robin Wright, joined by junior Doug Hayman a week later, turned in their draft cards to the local board. Some seniors with low lottery numbers — which meant they were more likely to be drafted — punched out stairway windows at Hedge; some needed medical intervention after chugging straight bourbon. My draft number was 153 so I didn’t panic; yet no one knew how long the war would drag on.

There were weekly teach-ins by student anti-war committees. Rich Goldstein ’71 and Bill Lowenstein ’72 organized meetings to plan out the next protest as the war dragged on.

I bought loose Indian-style shirts and an orange hammock from the Grand Orange on Canal Street. Incense filled our senses and Grace Slick and Jefferson Airplane belted out songs like “Volunteers” from their new album: “Look what’s happening out in the streets. Got a revolution. Got to revolution.” It became our anthem. My girlfriend and I edged into small-time Radical Chic (Tom Wolfe again) when we put on slightly tattered counter-culture wear (smock with head band for her; me in the traditional green and gold Dashiki she’d made me) to see Hair at The Wilbur Theatre in Boston.

We were just like everyone on stage: long hair, antiwar rebels. They dropped all their meager clothing when the curtain dropped, weed infusing the audience with contact highs. Irony settled over me like a warm buzz when I realized that right nearby in the Combat Zone, men and women were taking their clothes off every day to earn another kind of living, through peep shows, prostitution, and pornography.

Then came MacLean, who had come to Bates in September 1969. An ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, he was the college’s first multifaith chaplain. He answered questions with a drawl of his native Dorchester, Mass., as we raged about our pathetic lives. He always knew what to say.

We became DOGs: Disciples of Garvey (no one ever called him “Professor MacLean”). He held small groups or “micro labs” where we got into raps about parents, broken hearts, perfectionism, suicide, the war, and sex — “the penal-vaginal thing,” as he described it.

Garvey seemed to know and understand it all. Within days of his arrival, he was leading discussion group about human values and sexuality. He knew about women who broke out in hives because they thought they were pregnant, and others who were actually pregnant and went to Portland or beyond for back-alley abortions. How some of us dissolved under academic pressure or wanted to do the Timothy Leary thing and “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out.”

We asked a lot of him, but he only asked one thing of us, the DOGs: to come to New York City for his Short Term course, “Religion in the Secular City ” to “transpose our discontent into action.”

Begun in 1968 by MacLean’s faculty colleague Arthur Brown, an associate professor of religion, it was one of the college’s first off-campus Short Term courses. The course drew its name and its purpose from the famous book Secular City (1965) by theologian Bryan Cox, who urged readers to find a way to speak to God outside organized religion. “Standing in the picket line is a way of speaking,” he said. “By doing it, a Christian speaks to God.”

Garvey described the course as “Love in Action,” a call to understand that the real revolution was happening on the streets and to see the hypocrisy of modern religions that preached compassion but didn’t stand up to fight for people who needed their power. And we DOGs, didn’t hesitate. We hopped on his version of the Magic Bus to work our way into the preternatural mystery of the brio of Spanish Harlem.

Our work would be with the East Harlem Protestant Parish, an interdenominational ministry that was active from 1947 to 1975, focusing on social justice and community action.

But our base was in Manhattan, at the West Side YMCA, where there were few boundaries even though the sexes were separated. It was Hotel California as a script. One day, someone even asked me if I would lend him my girlfriend. And while it was not exactly like the Harrad Experiment, the novel about a college where men and women quite actively pursue coeducation (written, by the way, by Bates graduate Robert Rimmer ’39), but sometimes it felt that way.

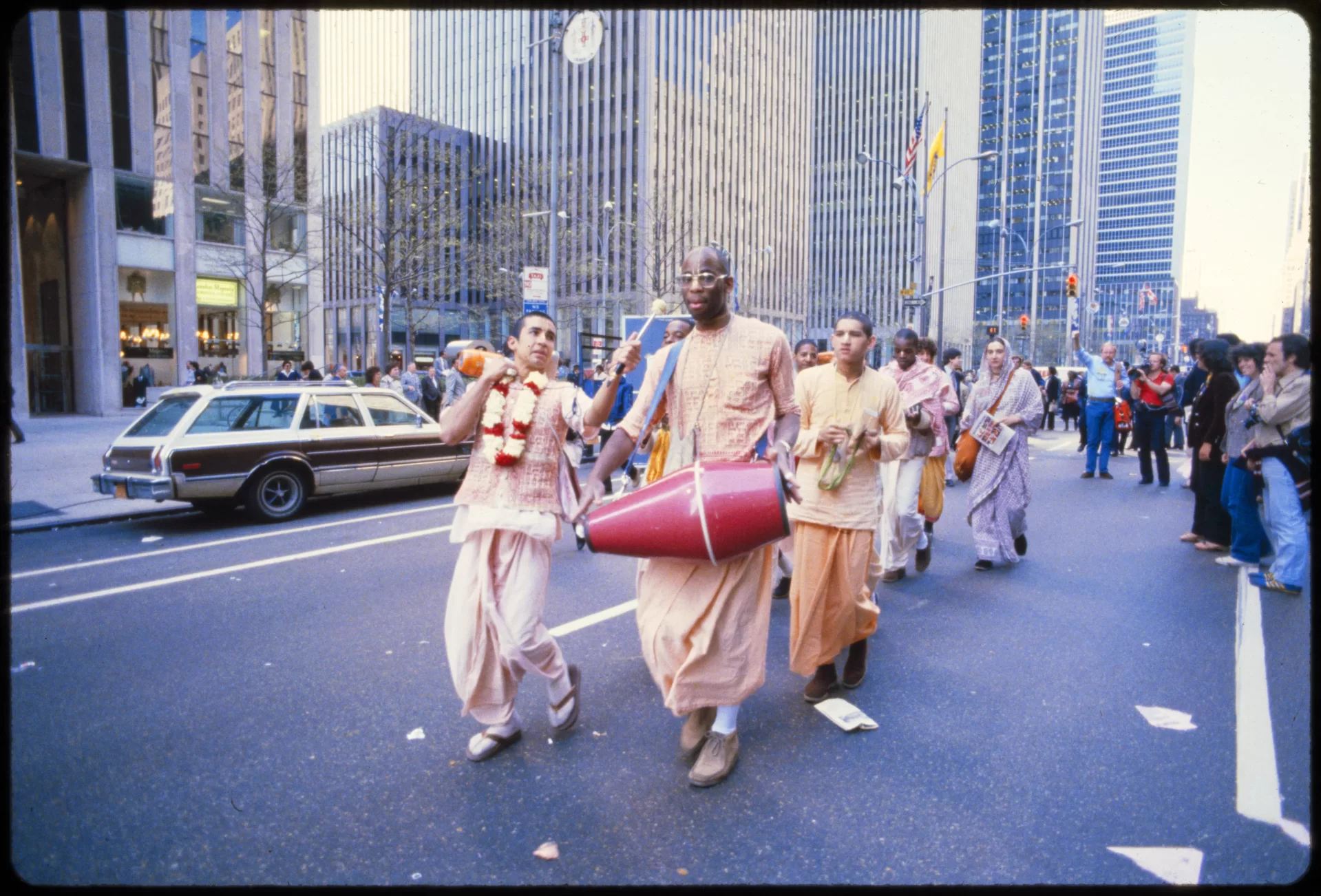

By 1970, it was clear that the wealthy city was nevertheless hurtling toward political, social, and economic dark days. It was the heyday of New York’s Hare Krishnas, and they were out in full force, chanting in their orange and saffron robes. Street jugglers threw red balls 20 feet in the air. Men fallen-down drunk snored in doorways. Glamorous women strode by in big hats and 6-inch heels. Young women in flowing dye-tied dresses sold flowers on the corners. Bankers and ad men sneered at it all.

Greasy-haired men dressed in rags begging for donations so they could get home to Arkansas or Toledo. Freaks with beads and headbands hustling you to buy their news sheets about where to find LSD and dope and support the revolution. Whole families appeared in raggedy street clothes performing folk music to raise funds for their commune.

It was as though Carlos Castenada had don Juan Matus put peyote in the water system, and I couldn’t wait to take a sip. We didn’t have long to wait. Soon, we were a small herd of white suburban virgins, pale as Daikon radishes, popping out of the subway at the Harlem–125th Street station ready to fight oppression.

It felt at first like a movie set but our senses quickly became overwhelmed. We smelled roasting meat, frying tortillas, rotting garbage, rain hissing on the sidewalk, and the permanent aroma of bodies sweating from the oppressive heat wafting up from the pavement.

We tried to take in a tornado of purple, green, red, orange, pink, and black shirts and pants moving in a swarm of smiling and yelling faces, black and brown, spilling onto and over broken heaving sidewalks. Music seemed to blare from every nook and window: funk, blues, rock, and cha-cha-chá played on guitars, congas, trumpets, and harmonicas.

Ostensibly, we were in East Harlem to help with anti-poverty efforts, including an octopus-like agency called Massive Economic Neighborhood Development (MEND), one of the many nonprofits created by President Lyndon Johnson in his War on Poverty program in the early 1960s.

But it didn’t feel like these folks needed help from a group of white kids. I had seen hopeless, grinding poverty in Lewiston, where people knew they were poor. But here, there was energy. Artists drew murals on vacant building walls, on storefronts, and set up easels on the street in celebration of the spring and hope. Raw, wiggling, crazy, screaming hope. Everyone and everything was happening on the street.

Our boss at MEND was Blorneva Selby, supervisor of MEND’s community action program, who epitomized the convergence of all this energy. At age 44, Selby was in a hurry to help her children and her neighborhood, ready to lift them up with the power of a 747. She was a social worker / activist / pastor / grandmother / saint /wise counselor / translator humanitarian. A Black woman, she lived out of her heart, advocating for people, her people, all people. She lived in The Now.

For us, Selby was like Virgil escorting Dante through Hades and out the other side. She invited two of us to her lake home in Pompton Lakes, N.J., for a weekend. Her sweet Southern patois dripped with generosity. She talked about getting out of a bad marriage and about “no account” boyfriends — and fighting racism her entire life. She and everyone we met treated us with respect despite our youth, race, and heads stuffed with “knowledge.”

Although we were the only white faces in a sea of Black ones at her church, we were literally and figuratively embraced. Everyone sang. If it was off key and loud, it didn’t matter. The building shook and rocked with spirit.

At the opposite end of town, we went to the WASP-y Marble Collegiate Church in downtown Manhattan, where Norman Vincent Peale told parishioners they could think themselves to success. Here, the congregants — including powerful developers who were literally bulldozing neighborhoods in the name of urban renewal — sang in a whisper, as if unwilling to disturb the status quo.

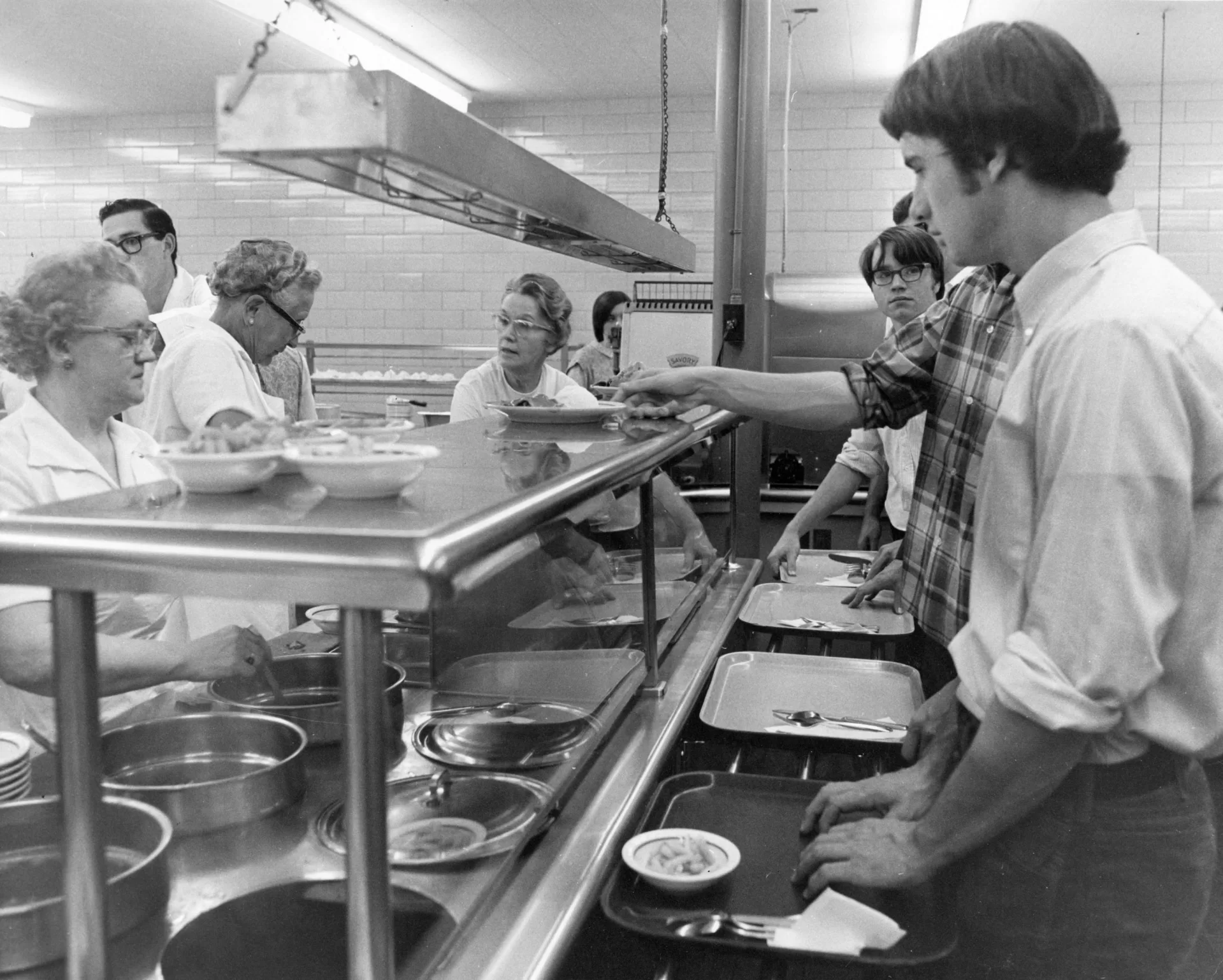

To survive in our new habitat, we ate on the cheap. We dined at the Horn & Hardart automat where workers shoved sandwiches and slices of pie into little cubicles that opened once the coins were dropped in. We practically lived at Blimpies, the sub shop around the corner. I saw the shredded lettuce in my dreams for months afterward.

We made it onto the Dick Cavett Show, knocked on Katherine Hepburn’s door (no answer), and loitered at museums and watched street performers for free. From the elevated train, we saw Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx stretching to the horizon with thousands of square, gray, unmarked graves that dwarfed my sense of being. We were children at play in the adult world.

By fall 1970, I had left the Fifties behind. The world had cracked open and there was no putting it back together. There were still Sadie Hawkins dances but the world was coming to Bates, and Adams 326 was my front row seat to the budding counterculture. I brought Spanish Harlem with me wherever I went, like Hemingway did with Paris, A Moveable Feast.

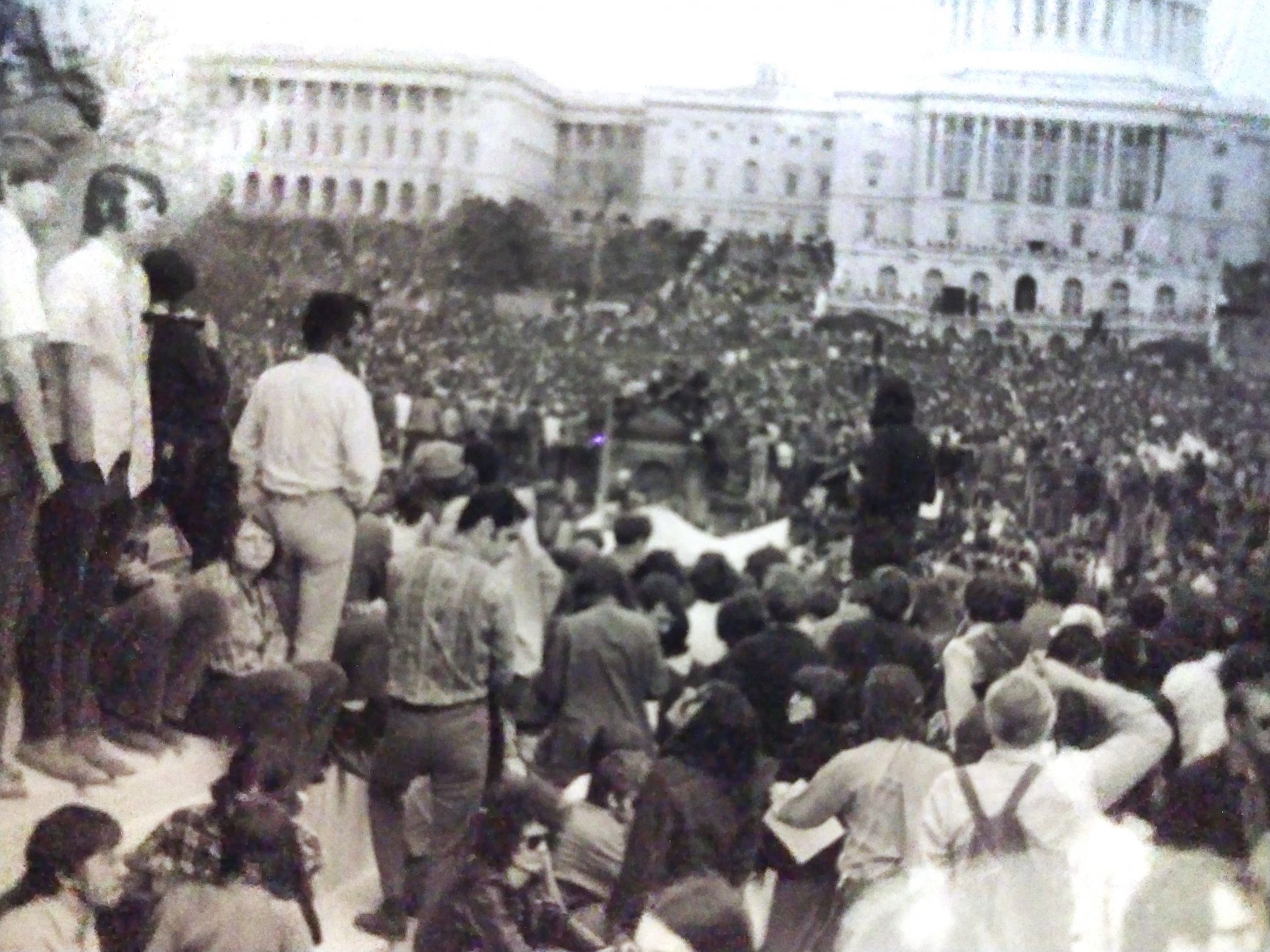

In April 1971, I joined other Batesies to march against the Vietnam War with 500,000 others in Washington, ready to enroll in McGill University if my conscientious objector application was rejected. At Commencement, Coretta Scott King gave a blistering speech denouncing the imprisonment of Angela Davis: “If her Blackness, her politics, and her womanhood are being judged, and not the crime, then all Americans will lose some of their liberties along with her.”

I wrote editorials for The Bates Student about the war and ending parietals, and wrote my senior thesis on Black Power. I was ready to fly.

From the influence of Spanish Harlem and my interests and talents, I fashioned a career in journalism. I wrote about the urban poor, rent control, and changing the justice system. About the sudden appearance of technology parks and displaced families undone by gentrification.

At some point, I grew tired of writing about the world. I had a dream in which I went through an Omega symbol archway with the word puerta, Spanish for “door,” inscribed above. I studied the classifieds and later that month I was assigned to work in Boston’s South End for the Massachusetts Department of Social Service. By 1980, it was Boston’s equivalent of Spanish Harlem.

I wrote my counseling master’s thesis about how to transform the foster care system and the best therapy to provide for the children and teens adrift in it, then worked in social services in Massachusetts and Maine.

And that’s what I and my fellow DOGs owe our mentor, Garvey MacClean: a path toward careers that were Love in Action, working on behalf of those who lacked a voice or didn’t have the resources to lobby for change.

It turns out that Short Term had a very long arm.

Mac Herrling ’72 lives in Bradley, Maine.