The survival of two trees, believed to be the oldest on campus, makes almost no sense. For at least 151 years, a hemlock and its next door neighbor, a red oak, have been growing closer together than probably any arborist would have recommended. On the new interactive historic map of Bates, they show up as two circles, touching.

Their branches overlapping in places, the hemlock and red oak are boxed in by buildings and structures — the flying staircase up to Ladd Library sweeps within about six feet of them — and are so near to Coram Library (completed in 1902), Carnegie Science Building (completed in 1912), and Ladd (completed in 1973) that it is a wonder they weren’t considered an impediment to any of those construction jobs and cut down. The trees are a little like Carl Fredricksen’s house in the 2009 Pixar movie Up, enveloped by growth, although in the trees’ case, not threatened by anything but age.

The historic map, a project of the Muskie Archives, debuted last fall, but was only viewable while using campus WiFi. It’s now available from anywhere with an internet connection, and in addition to giving historical insights into every building on campus over time, ivy stones, memorials and class gifts, it includes the option of exploring the significant trees of Bates. Courtesy of the research skills (and deep curiosity) of Sam Howes, the reference and digital initiatives archivist at the Muskie Archives, anyone can browse the history of these and 19 other campus trees through photographs, images, and captions.

The archivists found the first evidence of the hemlock and red oak on a map of Lewiston and Auburn created in 1875 by an unnamed artist and made available for sale in 1876 by J. J. (John Joseph) Stoner, a publisher based in Madison, Wis. It’s a bird’s eye view, which the Maine Historical Society allowed Muskie to reproduce for the historic maps project. How the artist got this view is a wonder: “I believe what actually happened is he would go up in a balloon,” Howes said. Presumably the daring artist sketched like mad while in the balloon basket.

The map’s precision makes it highly valuable to the Muskie Archives and the historic mapping project, which Howes and his colleagues Caitlin Lampman, the education and engagement archivist, and Pat Webber, the college archivist, began working on nearly two years ago, with a digital assist from Jake Paris, senior web developer and designer. “This is the only map from this time period that is accurate for the Bates campus,” Howes said. “Basically every other map drawn at this time showed the aspirational buildings that they were going to build,” such as a twin to Parker, on the other side of Hathorn. “A lot of those maps actually show it as though that building is there, even though it never happened.”

The hemlock and oak were sketched in ink as a tiny duo in an otherwise empty field, and in fine detail, the shape of a hemlock is distinctive. The two trees are still visible to anyone standing in front of Hathorn Hall, but in that era would have been essentially the only things visible in an otherwise unobstructed view of the Maine State Seminary building, aka John Bertram Hall, which was built in 1868.

Howes found a few key written records of the trees, first in a 1913 interview with Professor Jonathan Stanton, who believed that these trees had been natural growth. A November 1933 edition of the Bates Alumnus included a lengthy feature by William H. Sawyer Jr., Class of 1913, who taught biology at Bates from 1916 to 1962, titled “Our Campus Trees.”

“Of the original trees on campus,” Sawyer wrote, “if there are any, the red oak and hemlock at the corner of the Carnegie Science Building, three large elms on Campus Avenue, and the mixed hardwood and evergreen growth adjacent to the heating plant and ‘Lake Andrews’ are probably the only survivors.”

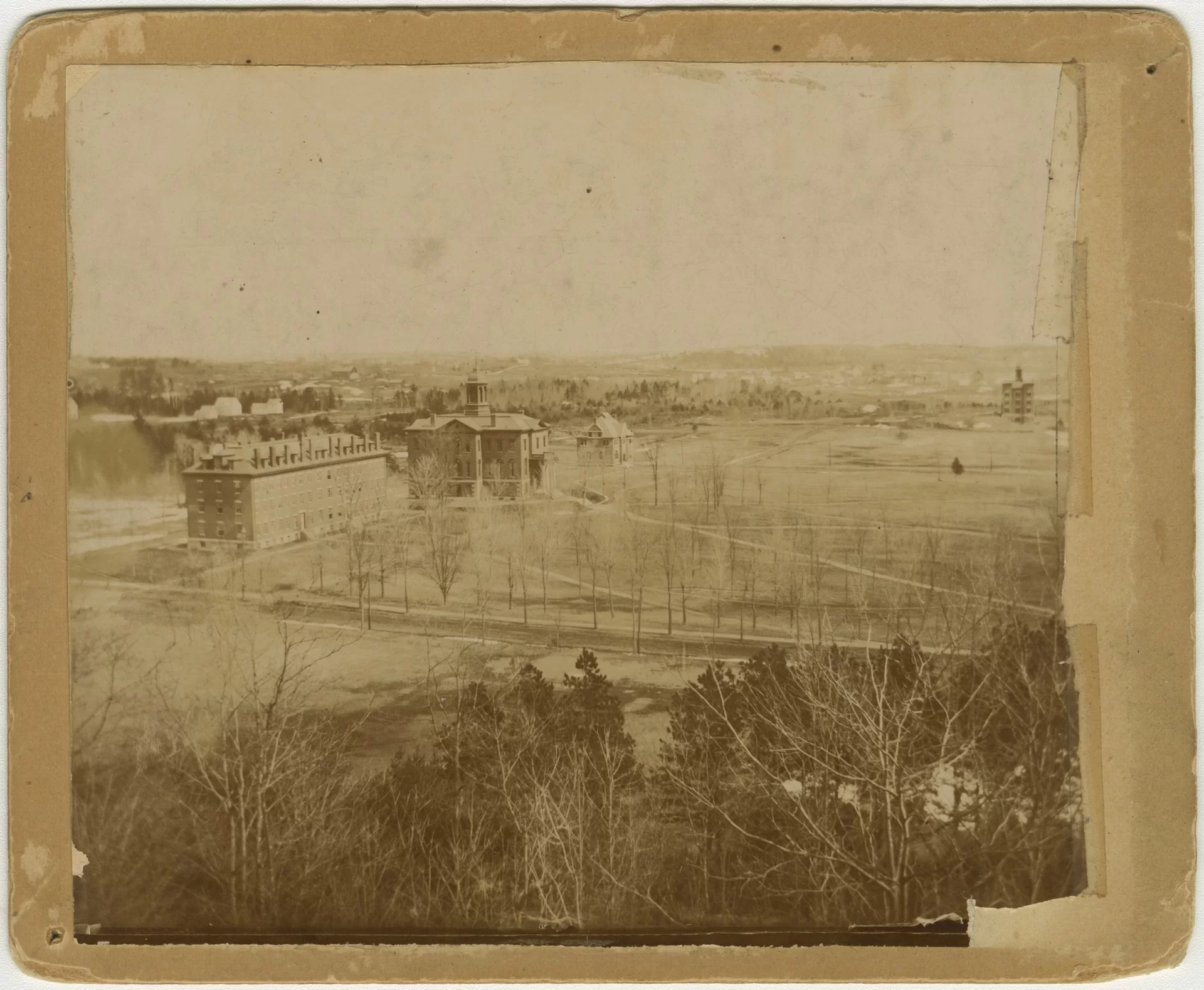

The Muskie Archives has added images of the trees whenever possible (some trees noted on the map live on only in memory, but there are some lush vintage photographs of the elm planted by the Class of 1870, which came down likely after the 1950s). In addition to that 1875 bird’s eye view, there is a very early photograph from 1890 that shows the hemlock and red oak, and another taken from Mount David in 1903, after Coram was built, that shows the oak beginning to develop its sprawl and surpassing the hemlock in height. A photo from 1910, taken from John Bertram, shows them from the other side.

The historic campus map project has been almost two years in the making, but it may never be “done.” That’s because little tidbits of knowledge, some in the form of images, others written documentation, or accounts from Bates people, continue to come in on a regular basis. Crowd-sourcing will keep the historical map, like the campus itself, ever-evolving.

Additionally, there is the fact that Howes keeps finding new rabbit holes to go down. He’s spent a lot of time in archives of Lewiston papers, The Bates Student, and other publications. “And then you find stuff accidentally,” he said. Howes is more than okay with that; nuggets of information worth adding to the map are true treasures. “I’m actually in the middle of scanning a bunch of things now that I’m like, ‘Oh, OK, I need to add that in,’” Howes said, sounding utterly delighted.