Classical and medieval studies survey introduces field, faculty too

Framed by a student’s arm and thermos, Associate Professor of English Sylvia Federico listens to Gerry Bigelow discuss archaeology during a March 2015 class session of Introduction to Classical and Medieval Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

We’re looking at a map of Britain covered with black dots, projected on the big screen.

Historian Michael Jones, an expert on Roman Britain, explains to the class of first-years and sophomores that the dots mark where Roman colonists buried caches of coins for safekeeping. Some safekeeping: The coins weren’t unearthed again until long after their Roman owners were out of the picture.

“This is maybe the saddest map you’ll ever see,” Jones tells the students, who are in this Hathorn Hall classroom for a course called Introduction to Classical and Medieval Studies.

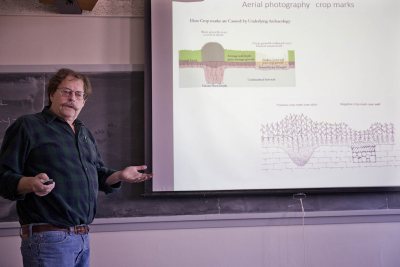

Professor of History Michael Jones describes what can be learned about Roman Britain from aerial photography during a March 2015 class in Introduction to Classical and Medieval Studies. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Jones is one of 13 faculty who taught the course this winter, including the English professor who designed it, Sylvia Federico. If that seems like an extreme approach to team-teaching, there’s a good reason for it: CMEN 103 is an introduction not just to topics in classical and medieval studies, but also to the scope of Bates’ program, in discipline and personality.

“Students get a sense of the field that’s much more comprehensive and dynamic than if it were just one teacher presuming to speak for the entire field,” says Federico. “It’s not just topics but methodology that’s on display. It presents material culture as well as literary culture.

“And I don’t think anybody else does that.”

On this Thursday in mid-March, Federico is at a desk among the students, listening to Jones present what he calls a “potted history” of the Romans’ four-century presence in Britain — a history, he explains, based largely on archaeological evidence. Sharing this class session is archaeologist Gerald Bigelow. (Jones works with Bigelow in an ongoing investigation into a vanished settlement in the Shetland Islands.)

Following Jones, Bigelow offers an overview of medieval archaeology that emphasizes what can be learned about commerce from, say, long-dead sheep parasites or the debris left behind when combs are manufactured from antlers.

Students in CMEN 103 listen as Lecturer in Archeology Gerry Bigelow discusses discoveries about medieval commerce. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

All of Federico’s colleagues in Bates’ interdisciplinary Program in Classical and Medieval Studies took at turn at the CMEN 103 lectern during the semester. Lisa Maurizio discussed the culture of anger in Homeric society. Margaret Imber explained the political value of Roman coins. Art historian Rebecca Corrie described how the Florentines of Dante’s day understood the classical world.

Laurie O’Higgins talked about women and humor, while Cynthia Baker, from religious studies, discussed desire and renunciation. Two guest lecturers shed light on interactions between medieval Western and Islamic cultures.

The course is intended in part as a recruiting device. “We want to introduce students from all across the college to the study of classical and medieval literature and culture,” says Federico. “We’re really trying to cast a wide net, and draw in people who might not necessarily thinking about majoring in it, or even pursuing it much beyond the 100 level.”

“The guest lectures allow students to meet the faculty and discover the range of interests and personalities that are drawn to the field,” adds Margaret Imber, “and hopefully find some sympatico profs they’d enjoy working with.”

But another objective of the course, Federico notes, is “establishing the idea that classical and medieval studies is integral to the liberal arts — that it’s part of our common mission and not a niche topic, but rather, relevant and important to modernity and to the future.”

For students, the “Ocean’s 11” approach to teaching demands some initiative in discerning connections between, for instance, medieval archaeology and the Old English poem describing the Battle of Maldon, circa 991, which the Anglo-Saxons lost to the invading Vikings. (A class re-enactment of the battle on Garcelon Field added a frisson of verisimilitude to the topic.)

For students, the “Ocean’s 11” approach to teaching demands some initiative in discerning connections between, for instance, medieval archaeology and the Old English poem describing the Battle of Maldon, circa 991, which the Anglo-Saxons lost to the invading Vikings. (A class re-enactment of the battle on Garcelon Field added a frisson of verisimilitude to the topic.)

The course has “taught me that there are so many different ways that you can approach a text,” says Hope French, a first-year student from London who, thanks to the course, is considering a CMS major. “You can explore its history and how that one text affected a culture years later.”

The course, in fact, is aimed at first-years and sophomores. That age group, Federico believes, is “really starting to come to terms with their own understanding of themselves as agents in the political world. One of the things that a class like this teaches is the ability to connect one’s own questioning about current affairs with timeless questions of the past.”

The Bates course is loosely modeled on Columbia University’s Literature Humanities program, an example of the “Great Books” courses that were a 20th-century staple. But, like Lit Hum and the 30 or so other descendants of the Great Books tradition, Bates’ CMEN 103 dusts off the hoary old gallery of dead white men and rehabilitates it for today’s broadened sensibilities.

For instance, still on the reading list is Virgil’s Aeneid, which functions in part as a tribute to Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. (Imber’s concurrent presentation looked at Roman coins as symbols of political power.) But, says Federico, “We’re reading Virgil with a critical eye that’s been informed by all those cultural conversations from the 1980s and ’90s that don’t just accept power on its own terms.

“We’re constantly interrogating issues of gender and politics, and how power is produced and held by certain groups over different periods of time and in different cultures. And how literature is quite often in the service of those forms of power.” Federico wants her students to ask, “What’s at stake, and what are the real-life consequences for the people on the ground?”

As American troops abroad continue to wage what Americans citizens at home increasingly perceive as “endless war,” in author James Risen’s words, Federico believes that in this sense, at least, the Great Books are only gaining relevance. Her students, she says, “are experiencing a time of war and questioning the meaning of war — as are these texts.

“I tell them, you know, when you go off to be advisers to a president or members of a think tank, these are the kind of questions you will need to ask about the causes of war, about gender and society, about power dynamics.

“This isn’t your grandfather’s Great Books class. This is something that’s really much more dynamic and engaging for modern students.”