Why newspapers and readers are at an ‘incredibly awkward moment,’ explains Boston Globe editor Brian McGrory ’84

Brian McGrory ’84, editor of The Boston Globe, visited Bates as the College Key Distinguished Alumnus in Residence on Jan. 27. Here, he visits students in a course on public opinion taught by Associate Professor of Politics John Baughman. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Brian McGrory ’84 and The Boston Globe began their love affair more than 40 years ago in Weymouth, Mass.: He as a paperboy, and the Globe as his paper.

“The only thing I ever wanted to do was write for a newspaper, and the only paper I ever wanted to write for was The Boston Globe,” he told a Bates audience last week.

While McGrory’s passion for the Globe has long since been requited — he’s been a Globe reporter, columnist, metro editor, and, since 2012, editor — the paper’s relationship with its readers is at an “incredibly awkward” moment, he said.

On the one hand, print subscribers pay a premium to have their newspaper arrive as regularly as the rising sun.

While the print circulation has plummeted, The Boston Globe has more readers than it’s ever had. But it’s not making much money from its large online readership.

“We have to nurture what we can get from print,” said McGrory, who was on campus as the College Key Distinguished Alumnus in Residence.

“Our print readers are paying top dollar. They are our most hardcore readers, our most faithful readers.”

But here comes the other hand: “We also have to understand that the future of our industry — undoubtedly — is digital.”

“I could come to a place like Bates and focus my life toward journalism.”

Early in his remarks in the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall, McGrory noted how Bates helped him along the route from paperboy to editor.

“I wanted the liberal arts,” he explained. “I wanted to expand my horizons. I wanted to learn about politics and literature and expression. Journalism is really about life, and I thought I could come to a place like Bates and focus my life toward journalism.”

Back in the mid-1990s, about the time McGrory was the Globe’s roving national reporter, New England had recovered from a recession, and the paper was again feeling good, generating more than $100 million in circulation revenue and $300 million in advertising revenue annually.

Help-wanted ads in the Sunday Globe alone could bring in $180 million each year, McGrory recalled. “Classified ads were the dirty secret of American journalism.”

All that revenue once funded an “enormous staff” of 540 Globe journalists (now 280), a 13-person Washington, D.C., bureau (now half that), and foreign bureaus (now none).

Nationally, U.S. newspaper print advertising revenues from 2005 to 2011 dropped from $50 billion to less than half that, and have been slipping 8 to 10 percent per year since then. Digital advertising is also falling, McGrory said.

All those declines obscure an ironic fact The Boston Globe has “more readers than we’ve ever had in the history of the paper.”

“You can’t compete with free,” McGrory added, mentioning Craigslist and similar free or cheap online sites to where the region’s Realtors, auto dealerships, and employee-seeking firms have fled.

Circulation declined as newspapers, at the dawn of the Web, “decided to give away the journalism for free,” a decision that McGrory compares to the owner of Macy’s deciding to open a new store where everything is free, “and then is shocked that people aren’t going into the old store to pay for stuff.”

The print paper’s Sunday circulation has shrunk from around 800,000 in the mid 1990s to 250,000 today, and weekday circulation from 500,000 to 150,000.

All those declines obscure an ironic fact. The Boston Globe has “more readers than we’ve ever had in the history of the paper,” McGrory says.

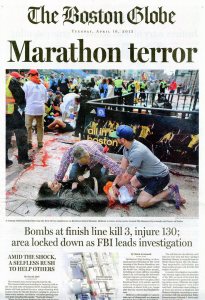

Of the Globe stories he’s been involved with, McGrory says he’s most proud of the paper’s coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing. Seen here is the front page of the paper on April 16, 2013.

The day before his visit, the Globe had 560,000 unique visitors to BostonGlobe.com and another 580,000 visits to the paper’s regional site, Boston.com. Digital subscriptions now top 70,000, the best among any regional newspaper.

Problem is, “we’re having a really difficult time making money from them,” he said.

McGrory doesn’t know how newspapers will move beyond this awkward time. “I have no idea, and anybody who says they do, they’re either lying to themselves or to you or probably both.”

Like any relationship fix, it will take a little of this, a little of that.

“You can’t give up on print too quickly and you can’t embrace digital too quickly. You need to make a nuanced and sophisticated transition.”

He told the Olin audience about two papers that lacked those two qualities.

The Orange County Register thought the answer was to be “committed to the print product,” McGrory said. “The paper tripled its reporting staff, but by 2014 the paper’s publisher had to slash its staff and change its management team.”

The CEO of Digital First Media, once the country’s second-largest newspaper chain, “mocked print” and put great emphasis on his newspapers’ websites, only to find that the revenue “just wasn’t there.” His papers have “gone to the auction block with very few takers.”

“The very foundation of a strong democracy depends on this issue getting fixed.”

If McGrory were the head of the Association for the Support of Drive-In Theaters, his lament might bring a shrug and a nod. Times change.

But, says McGrory, more is at stake.

“I don’t think it’s an overstatement to argue that the very foundation of a strong democracy depends on this issue getting fixed.” He added:

Newspapers in general, and, in my experience, the Globe in particular, form a bond with the community in a way that no other provider can possibly do. We live in a crazy, polarized society where presidential candidates hurl themselves at each other rather than talking about policy proposals. We live in a divided country where cable news analysts are racing to be the most bombastic possible. It’s noisy. Washington is at a standstill. The tone, not only in Washington but the state capitols, is deteriorating.

We, as the newspaper industry, are in the best position to make sense of all this. We alone can package all this information carefully, can be as fair as humanly possible, and add the context and respect that’s needed. In a crowded, jam-packed and violent world, we end up being an arbiter of what’s fair, what’s true, and what’s not.

Brian McGrory ’84, editor of The Boston Globe, greets Julia Mongeau ’16 of Melrose, Mass., editor of The Bates Student, during an audience Q&A after he spoke at the Olin Arts Center during his visit to campus as the College Key Distinguished Alumnus in Residence. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

After his prepared remarks, McGrory, a political science major at Bates who was a Bates Student reporter, news editor, and features editor, sat for a Q&A with his counterpart on the Student, editor Julia Mongeau ’16 of Melrose, Mass.

Asked about the Globe stories he’s most proud of, McGrory talked about the paper’s Pulitzer-winning coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing:

We made a commitment that night that we were going to be the paper that stuck with the Marathon story and told the victims’ story for a long time. We were not the national media who would come and go. We were going to be the arbiters of what was true and what was right and we would not rush to judgment. That has been a very proud moment that really stands out.

Mongeau’s questions also gave the elder editor a chance to offer bon mots for Bates. About the current Bates campus, McGrory said:

I haven’t been here in 20 years. I’m floored by the sheer beauty of the campus, the way the college was able to integrate new buildings with old buildings, and turn old buildings into really useful buildings. [Roger Williams] used to be the dorm you wanted to live in for all the wrong reasons, and I always thought it was one April rain away from collapsing. It is now a stunning building.

About Bates’ reputation in the Boston area:

Bates is just a hot school right now. Everywhere I go I always hear about Bates. My friend’s kid is just desperate to get here. It’s a really desirable place for kids to get to right now.