It was a rare opportunity for a Bates student: a visit to the New York City studio of a nationally acclaimed artist to purchase works for the permanent collection of the Bates College Museum of Art.

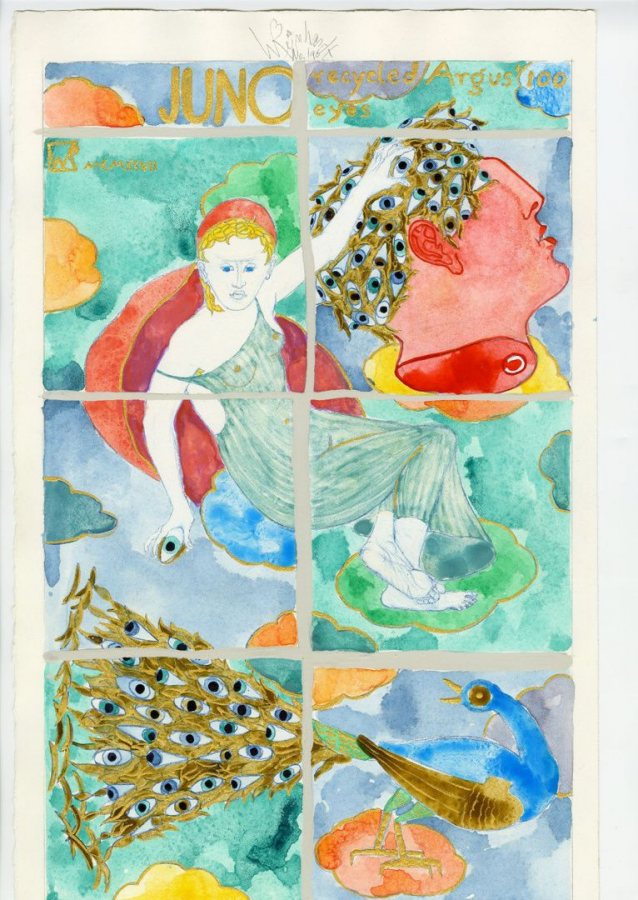

Wally Reinhardt, a painter known for his depictions of mythological scenes from Ovid, has been featured at the Bates museum before. “His studio was full of life,” says Lillie Shulman ’17 of Brooklyn, N.Y., who visited Reinhardt on the Upper West Side with Bates museum staffer Anthony Shostak. “We were surrounded by his bright and colorful works hanging on the walls.

“I was really honored to have that opportunity,” adds Shulman, a double major in art history and French.

Lillie Shulman ’17 of Brooklyn is shown amidst the Bates Museum of Art exhibition Mythology, which she helped curate. Hanging at left are watercolors by Wally Reinhardt. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Shostak, the museum’s education curator, brought Shulman along on the June 2015 acquisition trip to make use of insights she’d gained in helping to develop an exhibition for the Bates museum: Mythology, which shows through Dec. 23. Reinhardt is among artists represented in the show, which consists of works, largely selected by Shulman, from the museum collection.

During her sophomore year, in an Educational and Interpretive Programming internship under Shostak’s supervision, she had done substantial research and developed a curatorial direction for the show. This developmental process, routinely assigned to interns, both gives the museum a leg up on future exhibitions and steeps the student intern in the nuts and bolts of exhibition design.

While Shostak set no strict parameters for the exhibition, Shulman determined that a show about classical Greco-Roman mythology would make the best use of the museum’s resources. To better understand the artworks and the ancient narratives, she dived head first into a research process that included consultation with scholars on campus and with local art historian Eric Hirschler.

Developing the show was very collaborative. “An awful lot came from Lillie,” Shostak says. “I would present her with open-ended questions, but then I could also push her to take an idea a little bit further.”

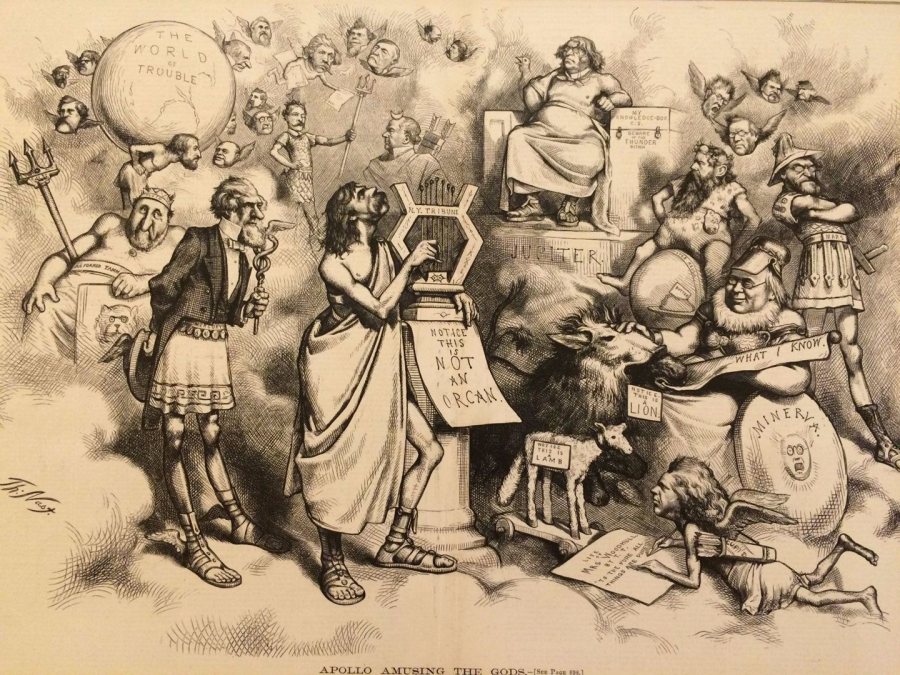

Once Shulman had a grasp on the various narratives in individual artworks, she had to find a way to tell a story using those narratives. The pieces chosen range from the 16th to the 21st centuries, are the products of 13 different artists, are in varying media, and represent their subjects in vastly different ways.

“As installations of objects, these shows can potentially look really disparate,” Shostak said. “Aesthetically, how do we utilize some strategy to bring it all together?”

Given classical mythology’s long influence on literary and visual culture, Shulman wanted to highlight how artists’ interpretations and depictions of the myths over the centuries have changed in keeping with cultural change.

For example, a 1992 digital photographic depiction of the Three Graces by artist Del LaGrace Volcano, “brings up issues regarding feminism and homosexuality,” Shulman says.

Lillie Shulman looks at watercolors by Wally Reinhardt in New York City in June 2015. (Anthony Shostak for Bates College)

“Including more contemporary work makes it a little more exciting,” says Shostak, “and that also ties in with recent books and movies that directly relate to those subjects.”

By the end of her internship, Shulman had created a strong basis for this exhibition. But there was no timetable for implementing it, and that’s not unusual. “We never actually moved to total completion through the internship,” Shostak says. Instead, Shulman was assigned to “generate much of the background for something that we could hold in our hand until we needed it.”

A year after the visit to Reinhardt’s studio and after a full year studying in Paris, Shulman received word from Shostak that he wanted to resurrect her mythology exhibit for the museum. “I never thought that this show would be executed during my senior year,” Shulman says. “It was really wonderful to hear that, two years later.”

Shulman was in New York for another internship that summer, but didn’t hesitate to help finalize the show, albeit largely via email and software that enabled her to experiment with different arrangements of work in a digital Bates College Museum of Art.

Shostak was equally pleased to have Shulman’s help, especially during the crunch time at the end “when she was looking at wall labels, proofing, rewriting, and reprinting.” The exhibition opened the week classes began at Bates.

Shostak is impressed by Shulman’s above-and-beyond commitment of time and effort to the show. “She had totally fulfilled all of her requirements a long time ago but was invested personally in the project and wanted obviously to see it through to completion,” Shostak says.

And Shulman? “I’ve always had a strong interest in museum administration and business departments,” she says.

“At the Bates museum, I had the exciting opportunity to step outside of my comfort zone and learn about the inner workings of the curatorial domain. This experience has encouraged me to consider pursuing more projects and careers where my curatorial skills can be applied.”