If there’s an atlas of the roads to hell that were paved with good intentions, special mention must be made of the 17th-century Puritan effort to convert New England’s Native Americans to Christianity.

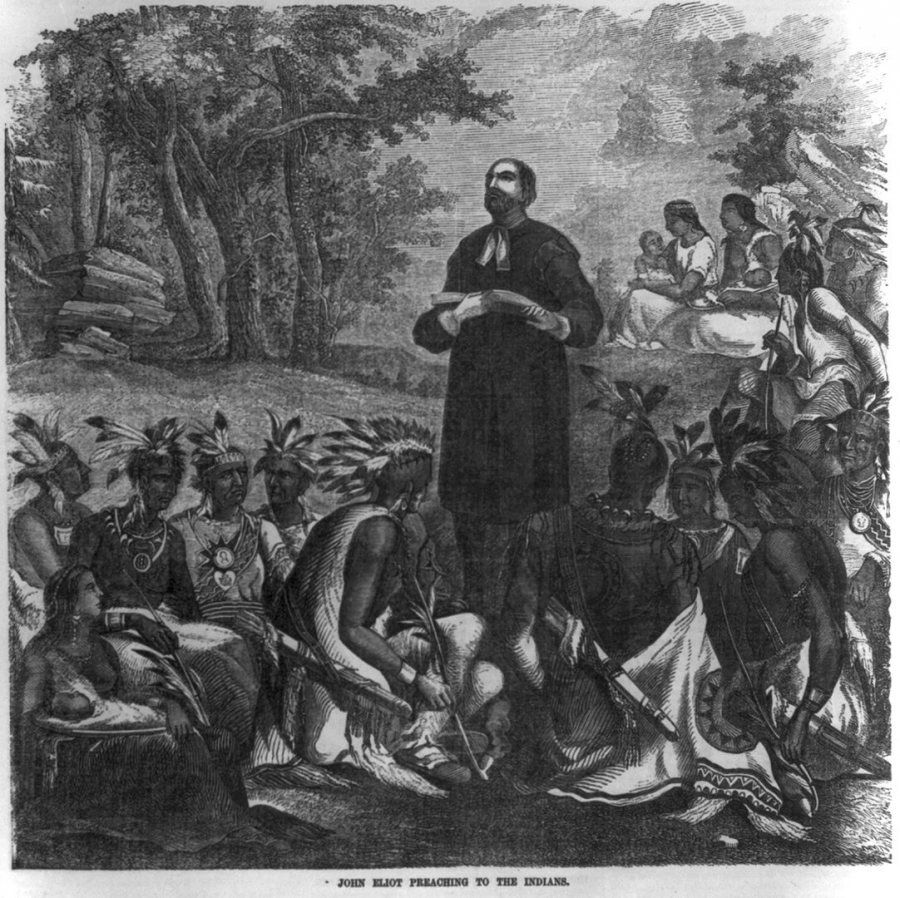

Benefiting from an early harmony between the natives and English colonists, the effort gained substantial ground for decades, largely due to the exertions of the Puritan John Eliot, who made it his life’s work to convert the natives.

Paralleling this cultural encroachment, of course, was the territorial grabbery that was practiced by growing numbers of colonists throughout the century, and that ultimately led to the outbreak of war between Europeans and Native Americans in the 1670s.

A poet and Bates faculty member, Robert Strong explores the origins of that devastating and transformative war, known as King Philip’s War, in his latest book, Bright Advent. The book focuses on Eliot; Metacom, aka King Philip, chief of the Wampanoag in Massachusetts; and John Sassamon, a Massachusett who worked with Eliot to translate the Bible into Algonquian, and whose murder begins both Strong’s narrative and the war.

Robert Strong reads “Anne Eliot” from Bright Advent:

A writer should consult period documents before rendering history as poetry, but Strong goes a step further with Bright Advent. The book combines his original poetry with verbatim excerpts from 17th-century documentary materials, notably letters and other writings by Eliot.

Director of national fellowships and a lecturer in English at Bates, Strong spoke to us about the use of single quotation marks, the power of Puritan language, and a prayer he wrote for the Big Mac.

What’s your book about?

The book is about the translation of the Bible in a collaborative project between Puritan ministers and native linguists. The attendant missionary work around that project involved a lot of real estate deals, trying to get land for “praying Indian towns” — communities of Christianized Native Americas.

What really was earnest and kindhearted work from John Eliot was contributing to what was essentially genocide of the local native tribe, and in large part helped lead up to King Phillip’s War. So the book is about those tensions.

What really was earnest and kindhearted work from John Eliot was contributing to what was essentially genocide of the local native tribe, and in large part helped lead up to King Phillip’s War. So the book is about those tensions.

The book opens with the murder of John Sassamon, which gave the English the excuse for going to war. And then the book goes back in time and follows Sassamon forward through the translation and conversion work, and his own conversion to become a minister in a praying Indian town.

Talk about your use of archival material.

I’ve worked with archival material on and off since I started writing poetry. And I’ve been fascinated with the language of the 17th century, and with the context of this cauldron of the beginnings of America, which involved so much conflict and the intensities of religion, and multiple cultures coming against each other.

There are huge gaps in the archive — we don’t even have the voice of the English women from the 17th century. And so, as a human being and a poet, I know that there’s a huge emotional and human landscape there, and I wanted to figure out what it might be. In creating the book, I used the archival language for a sort of linguistic momentum, to carry beyond the end of that archival page into the actual lives of the Puritans and the natives.

So I invented human relations for them that we don’t get from the archives. Sassamon and Eliot translated and printed the entire Bible together, so I had to describe the friendship that had to be there. And I gave voice to a female Native American who I put in a relationship with Sassamon, and I gave voice to Anne Eliot, John’s wife.

From an editorial standpoint, your treatment of the archival material is unorthodox.

I use single quotes to indicate the archival material as gently as possible. So, some people would say, “Well, you need to cite the material and say exactly where it comes from.” But that would highlight it, and I actually did not want to footnote. So it’s not a scholarly use of material, though the bibliography mentions all the sources.

But one thing I did at my editors’ request was to find a historian to write the introduction. They wanted a historian to weigh in, to say, “Actually, this is a very curious, an intriguing use of source material that raises interesting questions, even in a book of poetry.”

That was Christine DeLucia, who teaches indigenous and colonial histories of the Northeast at Mount Holyoke. She works in part in memory studies, and she has a forthcoming book about how King Philip’s War is remembered in the Native American communities of the Northeast today.

How does this book align with your earlier work?

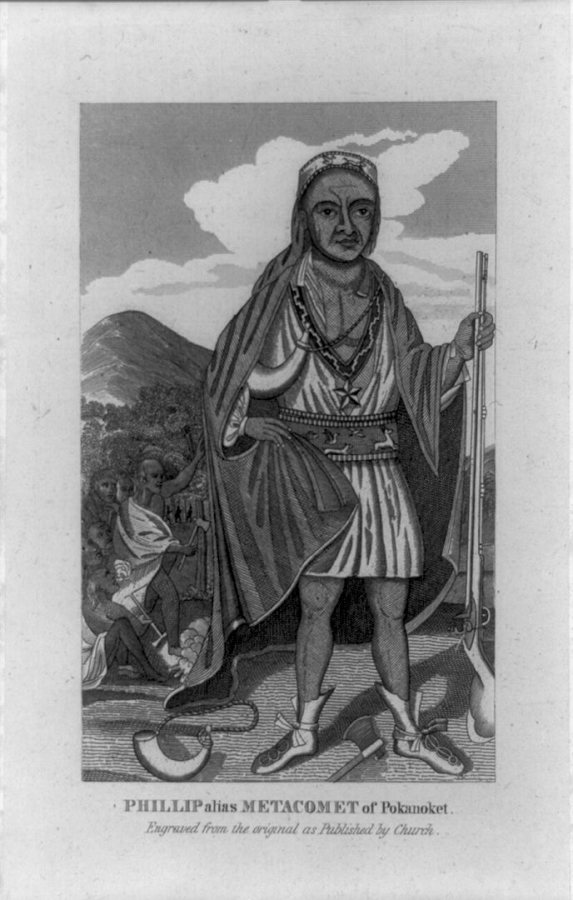

The Wampanoag chief Metacomet depicted in a copy of an engraving by Paul Revere, published in The entertaining history of King Philip’s war, by Thomas Church, 1772. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

My first full-length book is called Puritan Spectacle, and I wrote it coming out of research into Puritan conversion narratives at the Massachusetts Historical Society. It’s a very different book — individual poems, straight poetry, and they don’t make a story. I was looking for the roots of our contemporary consumerist culture in the English language as it first arrived on these shores.

We’ve inherited a style of language that came down across the myths of things like Thanksgiving and the Pilgrims, and those poems infuse it into our contemporary landscape. For example, I have a prayer for Big Macs, a prayer for cheerleaders, a prayer for the mall, and so forth.

When I was doing the research fellowship at the historical society, I was actually the first poet who’d ever gotten this particular fellowship. They didn’t know what to do with me.

There was this night where they would host the research fellows and bring in local historians and people who were interested. You were supposed to read from your work and then talk a little bit. And I read them the “Big Mac Sacrament,” and the look on their faces around the table, I will never forget it.

While I was there, I discovered unpublished letters of John Eliot that appear in Bright Advent. Some of them are his bureaucratic queries and pleading for money to the government of Massachusetts Bay and to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel back in London.

Those letters were so striking both because of their urgent concern for the souls of the Native Americans, and because of this kind of committee-meeting savvy that we’re all familiar with [laughs]. But that’s within the framework of our knowing that his work is contributing toward a war that was eventually just devastating for everyone.

What interests you about 17th-century America?

These are people who are speaking and writing in the same historical and linguistic moment that Shakespeare is. The language is both completely foreign to us and utterly recognizable. The Puritan ministers were so highly educated and articulate, and they had their Hebrew and their Latin.

So their sentences are beautiful, and since most of those sentences are saying something about the beginning of what became America, I find it just to be so powerful and resonant.

You’ve done a few public readings from Bright Advent.

A couple were during the big Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference in Washington in February. One of those was in a really loud bar in a Korean restaurant.

At these conferences, most of the readings are group readings where you’re one of 10. And I was like, “Wow, what am I going to do?” So I just chose the opening murder scene and screamed it. And so that worked really well! It was a murder scene screamed in a bar.

And back at Bates, you read during a {PAUSE} gathering.

It was amazing to read in Gomes Chapel because all the characters in this book are so saturated — both in their actual lives and in the story that I tell — with the pressures and intensity of religious striving. So to read it in the chapel space was really, for me just personally, really intense, after I had spent so much time with these characters.