If the government takes your house to make way for a highway bypass that will improve traffic flow, you’re entitled to (and may even get) fair compensation for that taking of your property.

But not all government takings are followed by recompense, nor are they even acknowledged as a taking. In the 1980s, for instance, municipal authorities in New York City closed gay bathhouses as a response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. They argued that the bathhouses were hot spots for transmission of the disease.

Whether or not the closures were defensible from a public health standpoint, fair compensation never entered the equation. Instead, the closures not only deprived bathhouse owners of their business income, but also deprived clients of a sociocultural milieu that was important and irreplaceable.

Timothy Lyle, assistant professor of English at Iona College (at left), and Stephen Engel, associate professor of politics at Bates, present research arguing that the 1980s closure of New York City’s gay bathhouses was an act of “dignity taking” from the gay community. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In short, as professors Stephen Engel of Bates and Timothy Lyle of Iona College argued during a March 2 talk at the college, the bathhouse shutdowns constituted a “dignity taking”: a confiscation of property, made without just compensation or legitimate public purpose, whose goal is to infantilize or dehumanize the affected group. (It’s a concept originated by Bernadette Atuahene, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law.)

Engel and Lyle presented their recent research as part of an interpretive series accompanying the college production of Angels in America: Millennium Approaches. The lunchtime session in a Commons meeting room drew an enthusiastic capacity crowd, perhaps drawn in part by the talk’s title, which for the first time in this context at Bates dropped an F-bomb: “F***ing with Dignity: Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking.”

In June, the Chicago-Kent Law Review will publish the research by Lyle, a former visiting professor at Bates who is now an assistant professor of English at Iona, and Engel, a professor of politics who studies U.S. political and legal development and social movements, particularly involving LGBTQ issues.

What did the bathhouses mean to New York’s gay community in the mid-1980s? If many baths weren’t created “for the purpose of men to seek out sexual encounters with each other,” Engel explained, “by the turn of the 20th century, some became known as ‘favorite spots’ where same-sexual relations were not discouraged.

On Jan. 6, 1986, New Yorkers pass by the shuttered St. Mark’s Baths in Greenwich Village. The institution was one of many gay bathhouses that the city closed in the 1980s as a response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. The order to close is posted on the front door. (AP photo/Rene Perez. Used with permission)

“They provided space for men to socialize with one another as identifiably gay men,” Engel continued. “The gay bathhouse took on an even more symbolic value within the context of the 1970s when queer sex acts were articulated as a kind of liberation from heteronormative constraints.”

In a way, the bathhouses served as community centers, offering films and live entertainment, hosting benefits, and offering voter registration and screenings for sexually transmitted infections. (Bette Midler, it was noted, still regards her early-career performances at the Continental Baths as some of her favorite gigs.)

“Unfortunately, public officials’ first response to the crisis was to invade these community institutions as sites of the problem.”

“In short, the baths were sites of community and kinship formation that helped gay men to interact beyond the carnal.”

Yet that role was never considered by the authorities, said Lyle, nor were “queer understandings of space, contact, intimacy, and belonging that animated these spaces.”

“So to entertain any notion that these closures damaged the dignity of gay men, we must resist the urge to pathologize these public, anonymous, and casual sex institutions,” Lyle said. “But unfortunately, public officials’ first response to the crisis was to invade these community institutions as sites of the problem at the very time that [government was] underspending on HIV education, prevention, and resources for these communities under siege.”

The closures and the public debate surrounding them “violated the dignity of gay men in a few different ways,” Lyle said. The furor exacerbated a tendency to blame gay men for the epidemic. It overshadowed the gay community’s own substantial efforts to regulate the baths.

The March 2 presentation “F***ing With Dignity” drew a capacity crowd to a conference room in Commons. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Finally, public perception reinforced the authorities’ refusal “to engage in the queer logics that articulated the communal value of these spaces,” Lyle said. “Simply put, these bathhouses challenged the supposedly neat and tidy boundaries that separate the public from the private.”

The gay community’s own push to regulate bathhouse behaviors was a measure of the community’s determination and cohesiveness. Working with bath owners, organizations such as the Coalition for Sexual Responsibility and Gay Men’s Health Crisis undertook substantial campaigns to promote safer sex and to make recommendations, to be backed by inspections, for educational, hygienic, and structural improvements in the bathhouses.

Basing their presentation on archival research conducted in New York City in 2016, Engel and Lyle offered colorful examples of promotional materials from the campaign to self-regulate. Engel described a proposed poster design, listing high-risk practices to avoid, that proclaimed in bold type, “Sex is wonderful!” — and then warned, “But don’t let it kill you.”

Another poster reminded readers, “Affection is our best protection.”

The gay community’s effort to support the bathhouses, designed to balance health (and political) imperatives with sex-positivity and community solidarity, was aligned with some official resistance to closing the baths, in part on the grounds that closures would constitute excessive government interference.

New York City Commissioner of Health David Sencer was an opponent of closure, as were members of a state bathhouse subcommittee. But in adopting the CSR recommendations for bathhouse practices, the subcommittee also, in Engel’s words, “essentially co-opted the community’s efforts of self-regulation and stated them as their own.”

“Sex is wonderful! But don’t let it kill you.”

In October 1985, the state public health council amended the sanitary code such that “no establishment shall make facilities available for the purpose of sexual activities where anal intercourse, vaginal intercourse, or fellatio take place. Such facilities will constitute a threat to the public health.”

The council didn’t acknowledge, Engel explained, “that these institutions could be anything other than a threat to the public and that activities within them could be anything other than those that spread contagion.

“Furthermore, the provision made no distinction between high- and low-risk activities, and ignored the recommendations of the state’s bathhouse subcommittee, the community-based organizations, and contemporary medical science.”

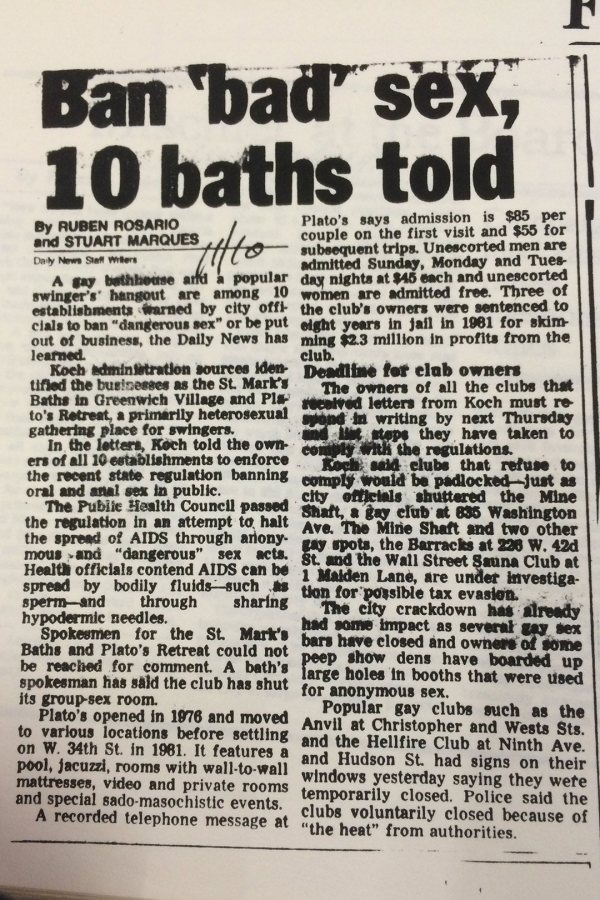

The New York Daily News of Nov. 10, 1985, covered the city’s edict against establishments permitting “dangerous sex.”

Ultimately, the city shut down most of the baths. “Elected officials painted gay men as oversexed animals incapable of responding to the crisis,” Lyle argued.

“The bathhouse closures perpetuated [a narrative of gay] culpability, ignited pretty serious divisions within the gay and lesbian communities, and produced within gay men, I think, a deep distrust and even fear of government — and one another, to be honest.”

The other side of the dignity-taking coin, of course, is dignity restoration. And while the rhetoric around U.S. Supreme Court decisions striking down sodomy laws and upholding LGBT marriage might feel restorative and uplifting, Engel argued that their conceptual underpinnings, in fact, are “quite narrow.”

“Even as we may recognize the momentous achievement that marriage recognition represents as a U.S. constitutional matter,” he said, the decision still privileges those gay unions that are modeled after heterosexual marriage, while ignoring “other kinds of connection at the heart of a queer ethic of public sex.”

By the same token, Lyle noted, the advent of so-called Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) — the ongoing administration of antiretroviral drugs to HIV-negative people who are at risk of infection — is a mixed blessing from the standpoint of dignity.

“Certainly the recent research is showing us powerfully that Truvada [the only drug approved for use as PrEP] is curbing HIV infection. There’s no debate about that,” Lyle said. But a prescription for the drug is overpriced, heavily regulated, and accompanied by data collection that Lyle characterized as state surveillance of gay men’s private lives.

“This approach to health,” he argued, “is problematically entangled in capitalistic enterprises and in state-directed efforts to surveil, police, and make decisions for gay men.”

In other words, Engel said, concealed within the seeming progress of sanctioned gay marriage and of sex made safe by Truvada is the same old refusal to comprehend “queer world-making practices.”

“While these efforts ostensibly return dignity to denigrated citizens — a lot of my friends and colleagues have talked about how PrEP allows individuals to have sex without fear for the first time — they do not engage deliberately with what exactly was taken in the first place, and how, and for what reasons, that taking occurred.”