Now finishing her junior year at Westlake High School in Austin, Texas, Annakate Kelley is looking ahead.

Next year, she’ll be vice president of the school’s famed drill team, and her college search is ramping up, too. Having just returned from visits to 11 mid-Atlantic schools, she’s at a familiar stage: “I have no idea where I want to go,” she says.

Kelley’s future is calling, but in recent months she’s also taken time to ponder the past. As part of an AP English project, she created a video tribute, based on her research, to the life and death of a beloved Bates alumnus, David Nash ’68, who was killed in Vietnam in spring 1970.

Bates alumni killed in Vietnam

Four Bates graduates died in Vietnam: Robert Ahern ’64 in 1969, Harry Mossman ’65 in 1972, Charles Pfaffmann ’67 in 1970, and David Nash ’68 in 1970. Allan Jordan ’65, who attended Bates briefly and later graduated from Union, was killed in 1968.

Along the way, she’s made contact with a slew of Nash’s friends from Bates, catalyzing an unexpected round of conversation and memory-sharing 50 years after his death.

“Annakate was able to tap into a store of knowledge and sentiment from 50 years ago, and she’s done more to bring Bates people together around David’s memory than she will ever realize,” said Bruce Stangle ’70. “We owe her a debt of gratitude.”

Annakate Kelley, a junior at Westlake High School in Austin, Texas, created this tribute video for her AP English class about David Nash ’68, killed in Vietnam in 1970.

Kelley’s project is rooted in her school’s AP English curriculum. Each year since 2009, junior AP students have read The Things They Carried, author Tim O’Brien’s collection of short stories about combat soldiers in Vietnam.

Then they research a person — assigned randomly — whose name appears on the national Vietnam Veterans Memorial and create a video tribute using quotes, photographs, and other ephemera, including letters home, plus the student’s own voice-over.

“It moved me,” said Mike Nolan ’69, a Vietnam combat veteran, after seeing Kelley’s video. Noting that it was created by someone encountering the war for the very first time, Nolan says that “her young age and time separation gives her a certain honesty without prejudice.”

Rebecka Stucky, a high school English teacher of 44 years, created Westlake’s Vietnam tribute program in 2009, gaining support from the school library to create a public site for the video projects. Since then, Westlake students have created an astonishing 4,292 tributes, including one for Charles Pfaffmann ’67.

Annakate Kelley, a junior at Westlake High School in Austin, Texas, created a tribute video to David Nash ’68, killed in Vietnam in 1970.

For her 16- and 17-year-old students, reading O’Brien’s book and creating the tributes “helps make the war more real, more tangible,” says Stucky. “They are near the age that some of their soldiers died, so it makes a tremendous impact on them. They begin to refer to the person they are researching as ‘my guy.’”

Such is the case with Kelley. As she began her AP coursework, she recalls how “it felt hard to find a connection to the war. It seemed so long ago.” After reading the book and creating the video, “it feels close.”

That proximate feeling hit its height as photos poured in from Nash’s Bates friends, including John Lanza ’67 and Bill Bensch ’67. In one, Nash is with a bunch of friends in Parker Hall. He’s grinning, a beer in hand, and more than a few of his buddies are flipping the bird at the camera. Did Kelley notice the gesture? “About the third time I looked at the photo, yeah,” she says with a laugh.

David Nash ’68 (standing at right, beer in hand) and bird-flipping friends pose in West Parker Hall in October 1965. (Photograph by Bill Bensch ’67)

Seeing him in his Bates environment, with friends, beer, and laughter, changed her perception of Nash. “At first I thought of him as a tough soldier. But he was just a kid.”

O’Brien’s book is about the literal and metaphorical things that soldiers carried with them in Vietnam. Nash carried “love for his sister and his mother,” Kelley believes. “I think that’s what was getting him through, thinking of them.”

Nash’s mother died in 2010 (his father had died when he was 5 years old). His sister, Susan Rice, lives in Brewster, Mass., with her husband, Jonathan. She loaned Kelley letters that her brother wrote from Vietnam, letters filled with now-familiar sentiments of growing disillusionment, frustration, and fear.

It was hard to re-read his letters, says Rice, and the experience revived some regrets. Four years older than her brother and already married and living far from home, she “didn’t even get a chance to see him play baseball” in high school or at Bates.

That’s been the hardest part of this experience, says Kelley, and what made her tear up at times: realizing that “the war still affects people every single day. People live with the pain of the war every day.”

The pain does endure, says Rice, but so does hope and appreciation.

“Annakate’s high school is not allowing their students to forget about this very sad chapter of American life,” Rice says. “In that sense, I feel good about it, the same way I felt about watching Ken Burns’ Vietnam War. It’s hard to watch, but good to always keep bringing those lessons forward.”

For Stucky’s students, reaching out to family and friends to learn about “their guys” becomes “an amazing experience to guide them in their discovery.” Importantly, the students “are creating something for a very real audience.”

At first, Kelley’s Bates audience numbered three. Reviewing Nash’s presence on various Vietnam tribute sites, including the Vietnam Veterans Virtual Memorial Wall, she saw tributes from Sal Spinoza ’68, Bill Penders ’70, and Charlie Buck ’70.

Buck lives not far from Nash’s hometown of Mountain Lakes, N.J., and as fate would have it, he’d recently visited a cemetery in Basking Ridge to find Nash’s grave. Then, he received an email inquiry from Kelley. “It almost knocked me off my chair,” says Buck.

After Kelley contacted the trio, they and others, including Lanza and Stangle, helped to widen the circle, which now includes well over 100 Bates alumni, not to mention friends from Nash’s hometown that Kelley contacted for her project.

Rice says that the pain of losing her brother is also lessened by knowing that “classmates and Bates friends still hold him in high regard.”

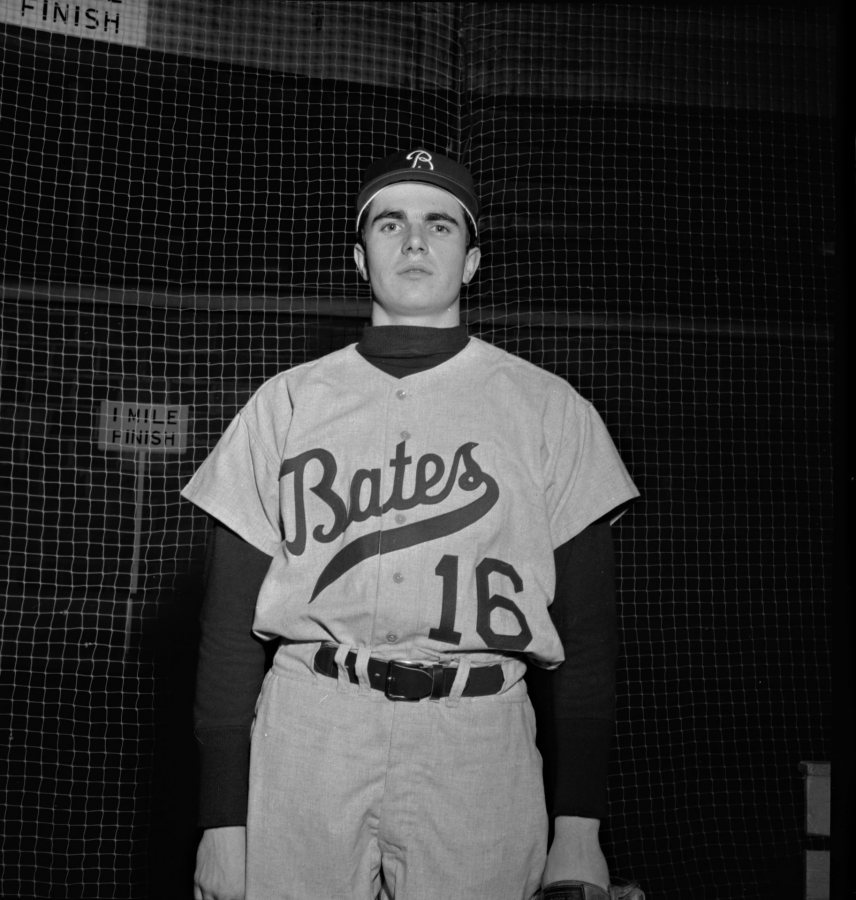

A pitcher for Bates, David Nash ’68 adopts a serious expression for his baseball portrait in spring 1967. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

And do they. At Bates, Nash played baseball, majored in history, and, in his senior year, served as president of the intramurals council. Friends told Kelley how Nash was a “really good kid,” a “Bates hero,” and a “first-class guy.”

To Penders, Nash was “wonderful, loving, sensitive, and kind.” And a letter to his hometown paper after his death called him “well-mannered, decent, and polite…. He only wanted to ‘play ball.’”

The outpouring tells Kelley something about Nash’s college. “Bates seems like a community where everyone is supportive,” she says. “Bates people seem to hold their connections forever, and I don’t think that happens at all colleges.”

Shortly after graduation, Nash was drafted to fight in Vietnam. He underwent a new type of Army training at Fort Benning, Ga., one geared toward filling a pressing need for more noncommissioned officers who could lead troops into battle.

Nash was tapped as his group’s “Distinguished Graduate” and promoted to staff sergeant. In his familiar self-deprecating and ironic tone, he judged the honor to be the result of “a calamity of errors” by the Army.

By September 1969, Nash was in Vietnam, but rather than the infantry, he was surprised to learn that he would command an armored cavalry assault vehicle, or ACAV, in the 11th Cavalry Regiment, 3rd Squadron, I Troop, 3rd Platoon.

In May 1969, David Nash ’68 is congratulated by First Sgt. Raymond Jenkins as a Distinguished Graduate of his noncommissioned officer training program at Fort Benning, Ga. (Photograph by Sgt. L. Herrmann)

“I know nothing about armor — its maintenance or operation,” he wrote. “I guess my first month will be ‘on the job training.’ It’s really typical of this ______ [sic] Army to train me to be an infantryman and then put me with armor. C’est la vie!”

For the armored cavalry in Vietnam, missions came fast and furious. Considered the Army’s jack-of-all-trades, armored cavalry units were tasked with barreling into the jungle to find and engage the enemy. Being an ACAV commander “is not always conducive to good health,” wrote Nash. “I will be sitting in the open turret…firing a 50-caliber machine gun in plain view of everyone.”

Nash wrote about the dangers of RPGs, or rocket-propelled grenades, that “will go through an ACAV like a baseball goes through a window. That’s how we get most of our casualties (along with mines), and they really scare me.” Twice, Nash’s ACAV ran over a mine, and each time he avoided injury.

He also wrote about his perplexing encounters with civilians, mentioning Stars and Stripes coverage of the My Lai massacre in one letter and expressing the familiar soldier’s lament: “You just don’t know who to trust.”

David Nash ’68 sits atop his armored cavalry assault vehicle, or ACAV, in Vietnam in January 1970. On the back of the photo, he wrote, “I have to do something about that beer belly.” (Courtesy of Susan Rice)

By December 1969, after heavy fighting near the Cambodian border, his platoon, which was supposed to have 40 men, was down to 24. “All three of my crew are 20 years old — fresh out of high school. My gunner is a medic. That’s how hard up we are for men,” he wrote to his sister.

Still, his “gung ho” platoon leader, a first lieutenant, kept volunteering for extra assignments. “We have now been in the field for 32 consecutive days,” wrote Nash. The lieutenant, he added, “doesn’t think of his men enough.”

For Kelley, the event that defined Nash’s character came the day he was mortally wounded. A new soldier had been assigned to check the perimeter for land mines. And Nash, perhaps because of who he was or perhaps because of what he didn’t like about his platoon leader, or perhaps both, volunteered to take the new soldier’s place. During the patrol, on March 26, 1970, he stepped on a mine.

He survived the blast and the loss of his leg, but complications set in. On April 17, he dictated a letter to a Red Cross worker from his hospital bed in Japan. “My wounds have healed but I picked up intestinal problems, malaria, and other assorted problems,” he wrote to his sister. He was fed intravenously. “At this point I think I’d pay ten dollars for a cheeseburger.”

Nash died 26 days later, on May 13, 1970. He was 23 years old.

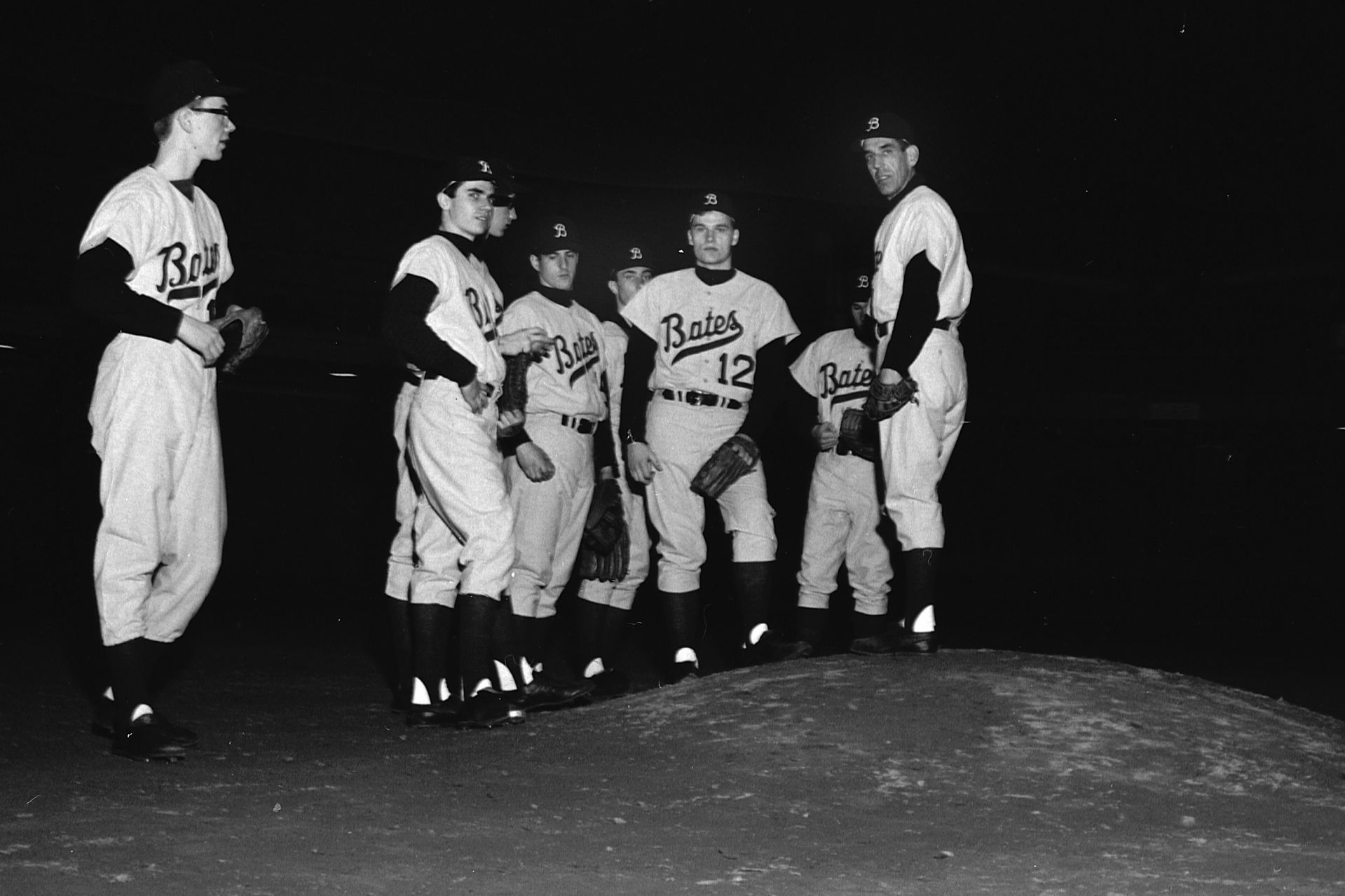

David Nash ’68 (second from left) and fellow Bobcat hurlers gather with their baseball coach, Chick Leahey ’52 (right), in the Gray Athletic Building in spring 1967. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

The next spring, his Bates baseball coach, Chick Leahey ’52, announced the creation of the David R. Nash Memorial Baseball Award, an effort spearheaded by Mike Morin ’68 and supported by teammates and friends of Nash. In recent years, his Bates friends have also endowed a scholarship fund in Nash’s name.

Leahey’s widow, Ruth Leahey, has seen Kelley’s tribute video. “I wish Chick were here to see it,” she says. “I remember when the call came that David was injured, and then a second call that he had died. Chick was deeply sad and frustrated by the loss of David’s life in the war.”

Years later, the Leaheys traveled to Washington, D.C. There, Chick went to the Vietnam wall, found David’s name, and knelt in prayer.