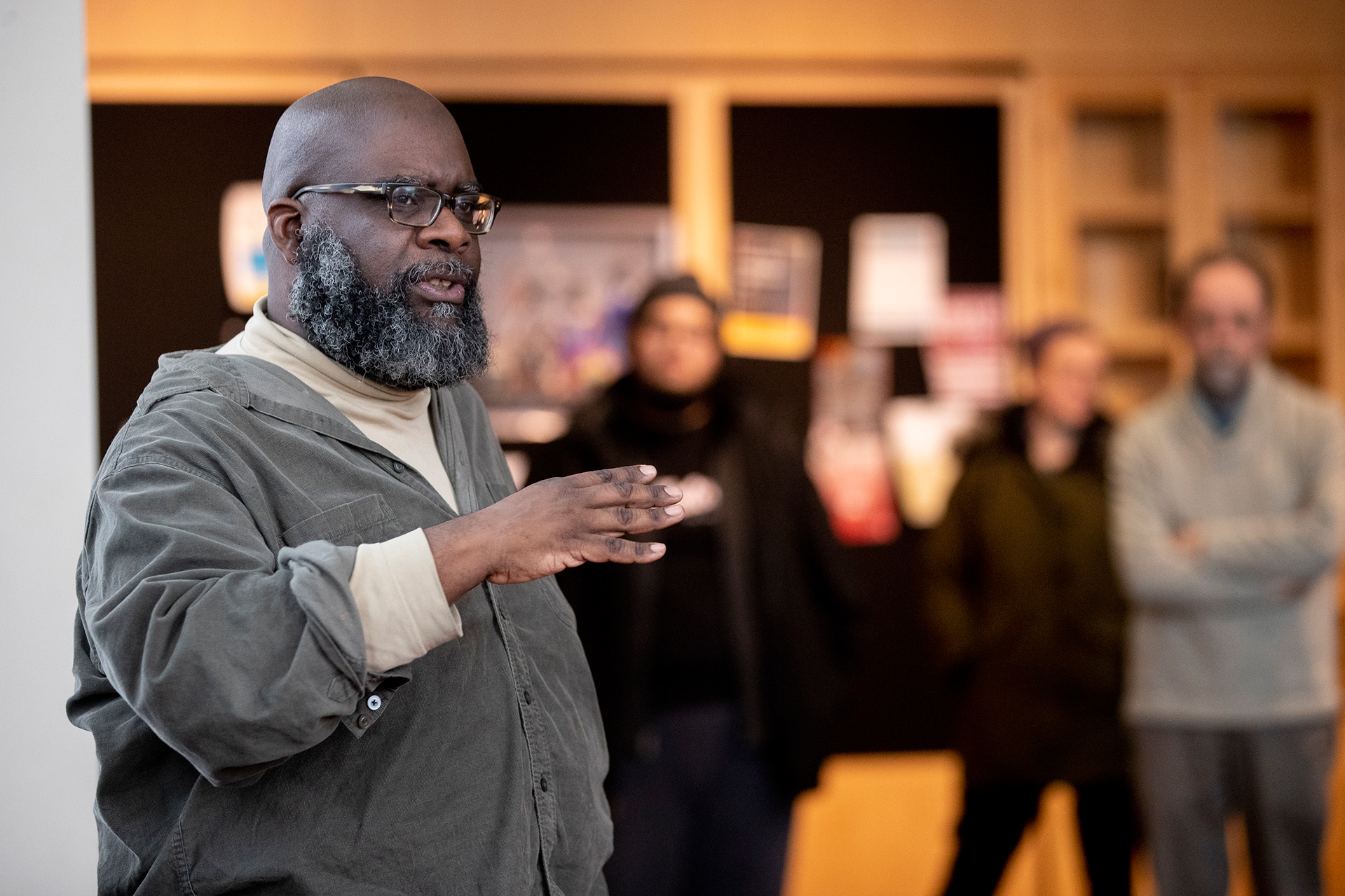

Observed every February, “Black History Month is a time that we get to think about, to celebrate black achievements,” says Charles Nero, Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies, and chair of the Program in Africana.

But in addition to that, “it’s a time to continue our discussion of race and white supremacy,” Nero says. “And I’m hoping we also think about and challenge anti-blackness — and by anti-blackness, I mean the ways in which we omit and evade discussions that affirm black people and our right to exist as citizens.”

Bates’ Africana program this month holds up such discussions in an especially engaging way: drama.

Using historical events as a basis to explore white oppression and black resistance are five plays: four written by Lecturer in Theater Clifford Odle, each based on actual incidents involving African American slaves in 18th-century New England, and a fifth, Janice Liddell’s Who Will Sing for Lena?, performed by Jes Washington ’13.

Five plays for Black History Month

Check out the times, dates and synopses for the five plays staged by the Africana program during Black History Month at Bates.

Why theater as a vehicle for Black History Month programming? As a performance medium, it gives every audience its own unique experience, Odle says. “It makes things, to me, more immediate, more alive, more visceral.”

“There’s a tradition of the dramatic form and black history that goes all the way back to W.E.B Du Bois’s pageant plays at the beginning of the 20th century,” Nero adds. “There’s a very deep tradition of black theater as a tool to educate about black accomplishment and to challenge anti-blackness.”

The Fireplace Lounge in Commons is the site for readings of plays during Black History Month that draw on historical events to explore white oppression and black resistance. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Washington, who has performed the one-woman Who Will Sing for Lena? since 2016, was a rhetoric major at Bates and this year will earn an MFA at the Actors Studio Drama School, in New York City. Liddell’s one-woman show depicts the true story of Lena Mae Baker, a domestic worker in Georgia who killed her white lover/abuser in self-defense in 1944.

Jes Washington ’13 appears in two performances of Who Will Sing for Lena? as part of Black History Month programming at Bates.

A jury of white men quickly found Baker guilty of murder, and she was the first woman to be executed by the electric chair in Georgia.

While Liddell’s two-act play grapples with oppression based on skin color and on gender, it’s a broad indictment of the abuse of power — or as Washington puts it, someone exercising “dominion over you just for the sheer hell of it.”

Lena, a dreamer, is “in the position where, no matter what she wants, someone is always dominant over her. She can’t get higher, because the person that is higher than her won’t allow her to do that. It’s her mom, it’s her employer, it’s society.

“She has a childlike quality to her that is beautiful when it’s time to be a child, but not so much when she should be an adult. She never really learned how to be an adult.”

The headstone of Lena Baker in Mt. Vernon Baptist Church cemetery, in Cuthbert, Ga. (Photograph by 86billy86 CC BY-SA https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Washington took the role, in part, as a way of coming to grips with trauma she suffered as a child. “Most of the women who were approached to do this role had similar experiences to the character and it was a little too much for them. So they all turned it down,” Washington says.

“It was very close to home for me as well, but I decided that instead of saying ‘No’ and running away from it, I wanted to use it, to heal from it.”

Early on, she says, “I was going through this process of healing, so it was more frightening every time I went up. There was only so much depth I could give it without crying uncontrollably onstage. But as the years have gone on, I’ve allowed myself to think extremely deeply into the character. Lena and I are quite one at this point.”

At Bates, Washington belonged to the Modern Dance Company and was one of the students who founded Sankofa, whose Martin Luther King Jr. Day performances examine stories and experiences of the African diaspora.

Advised by Nero, her rhetoric thesis looked at colorism, prejudice based on skin color, within black and Hispanic communities. Her thesis materials comprised a 45-minute video documentary featuring interviews with a host of Bates folks — and a 75-page written piece.

“Instead of saying ‘No’ and running away from Lena, I wanted to use it, to heal from it.”

She and her interview subjects, Washington says, talked about the effects of colorism “on minority mindsets — what we think about as far as what is beautiful, what is acceptable, what gets you along in this life. Or some of the things that our mothers would say when we were growing up because they just didn’t know any better.”

The products of assiduous research, including long hours in the Massachusetts Archives, Odle’s Colonial-era plays scrutinize a period in African American history that figures less in today’s consciousness than happenings in the 19th and 20th centuries. Yet there’s an intriguing parallel between the macrocosm of Colonial society and the smaller black world within it.

“Many of the ideas of liberty and independence that the Founding Fathers thought about and eventually fought over,” he explains, “were ideas that African Americans were thinking about and fighting over, even more so because they were dealing with slavery on top of that.

“So while John Adams and other folks can say, ‘Yes, these powers a thousand miles away are going to make slaves of us,’ there are slaves here saying, ‘Well, you’ve already made slaves of us, and we’d like to have a say in this.’”

Sam Alexander ’20, as Phoebe, speaks to Quaco (Dawrin Silfa ’21) near the end of the Feb. 6 reading of According to Mark. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

He says, “Black history in this sense is American history — it’s as much a part of the foundation of this country as Paul Revere’s ride and anything else any of the Founding Fathers did. So I think if you’re a serious about diversity, if you’re also serious about presenting different views of history, then you want to have a venue where these different views can be displayed,” that venue being Black History Month.

Looking at the status of both African Americans and women, Odle’s full-length Deerfield Homecoming combines and fictionalizes two separate historical episodes that took place in Deerfield, Mass.

One main character is Lucy Terry, a slave whose ballad poem “Bars Fight” is considered the oldest known literary work by an African American. The other is Eunice Williams, an English colonist who was kidnapped by the French and the Mohawks as a child and became assimilated into Mohawk society.

J’von Ortiz-Cedeno ’22 of Portland, Texas, asks a question after the Fireplace Lounge reading as Charlotte Lynskey ’21 of Costa Mesa, Calif. listens. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In real life, Eunice periodically visited her English family. In his play, Odle explains, Eunice’s father kidnaps her on one of those visits. He assigns Lucy Terry, Eunice’s childhood friend, to somehow try to reawaken Eunice’s pre-Mohawk identity.

Each around 10 minutes long, Odle’s other three plays in the Black History Month series are parts of Blood in the Revolution, a work in progress. Performed on Feb. 6, According to Mark is about “a slave who could read and was looking for a way to free himself from an oppressive master. And he felt the Bible provided a path to murdering him as long as he didn’t spill blood.”

The play is set during the planning of the murder, which also involved two other slaves, Mark’s sister Phyllis and a woman called Phoebe. In the actual event, Mark was hanged for the murder and Phyllis was burned at the stake — a punishment that in Colonial America was reserved for female slaves who kill their masters, Odle says.

Quaco (Dawrin Silfa ’21) makes a point to Mark (professor Charles Nero) and Phyllis

(Perla Figuereo ’21). (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Witness to an Execution deals with a literate slave named Andrew who was an important witness to the Boston Massacre, the 1770 killing of several colonists by British troops. As a slave, Odle says, Andrew “does not have the status in society that other witnesses did. So the play explores the kind of pressures that he may have faced in deciding whether or not to actually testify or get involved in white men’s business, as some people would call it.”

Finally, A Suit of Freedom focuses on a woman named Mum Bett, aka Elizabeth Freeman, who successfully won her freedom from slavery in a 1780 court case in Massachusetts. “Her case eventually led to the ending of slavery in Massachusetts,” Odle explains.

“And in that play, she has a discussion with her former mistress, who is trying to lure her back. I thought it’d be interesting to see what that conversation could have been like.”