“I wish you could smell them,” says Susan Reid ’79, looking down at a tray of English muffins she’s just pulled out of the oven. They’re steaming, golden, dusted with semolina.

Reid is addressing roughly 1,700 people who have gathered, via Instagram, in her home kitchen in Vermont, just a few miles from King Arthur Flour headquarters in Norwich.

Reid, a chef, editor, and senior recipe tester, has worked at the legendary flour company for 18 years. These days she’s also playing counselor to the tens of thousands of newly minted American home bakers with nearly that many questions.

Starting in March when the country started locking down because of the COVID-19 crisis, bakers, both veteran and novice, stripped grocery shelves of yeast and flour, and began home-baking everything from cakes and cookies to pizza dough.

Susan Reid ’79, a chef, editor, and senior recipe tester at King Arthur Flour, is also playing counselor to the tens of thousands of newly minted American home bakers. (Photograph by Andrea Brown)

Long-neglected bread machines were pulled out of cupboards and set to work. Photos of fermenting sourdough starters suddenly seemed more popular than selfies on social media.

Reid says King Arthur was prepared for strong sales in April, since the weeks around Easter are usually the second-busiest baking season (Thanksgiving through Christmas being the first).

But as they shut down their popular baking school in Norwich, which is too tactile and tourist-driven for remote instruction, and sent staff home to work, they weren’t prepared for an “at-home tsunami” of baking that has turned spring 2020 into the equivalent of a prolonged holiday baking season — and turned King Arthur products, and Reid’s skill set, into particularly hot commodities.

“We blew through everything on the shelves and were able to refill with the Easter supply,” Reid says a few days after the muffin-making appearance for cast iron manufacturer Lodge, on whose Instagram cooking show she’s becoming a regular. “And then the pinch hit.”

“Americans are so extreme. They think, ‘If yeast breads are good, sourdoughs are even better.’ They also think they have to maximize their time.”

The employee-owned King Arthur scrambled to address the supply-chain problem. There is plenty of wheat available — but with its usual mills already working overtime, King Arthur sought additional mills that could grind to the company’s precise specifications. They found one, but it only has the capacity to package in 3-pound bags. Soon that smaller size will show up online in place of the usual 5- to 10-pound options, allowing King Arthur to send more product to grocery stores.

Presumably, the home bakers who have been frustrated by empty grocery shelves will soon be able to get back to self-soothing with bread making. Reid absolutely understands that impulse. “The feel of dough is really soothing and therapeutic,” she says. “There is nothing better than a warm loaf of bread. It’s so enticing and rewarding. And everybody is stuck at home anyway.”

Jim Amaral ’80, the founder of Maine-based Borealis Breads, is also unsurprised that baking bread suddenly got trendy in a time of crisis. “When I am shaping bread it is like a Zen experience,” he says. “It’s calming and you feel like you’re doing something constructive.

“There’s all sorts of good, strong emotional context to the process. You’re feeding your family and it also speaks to a nostalgia for a simpler, home-based kind of life that we might have grown up with.”

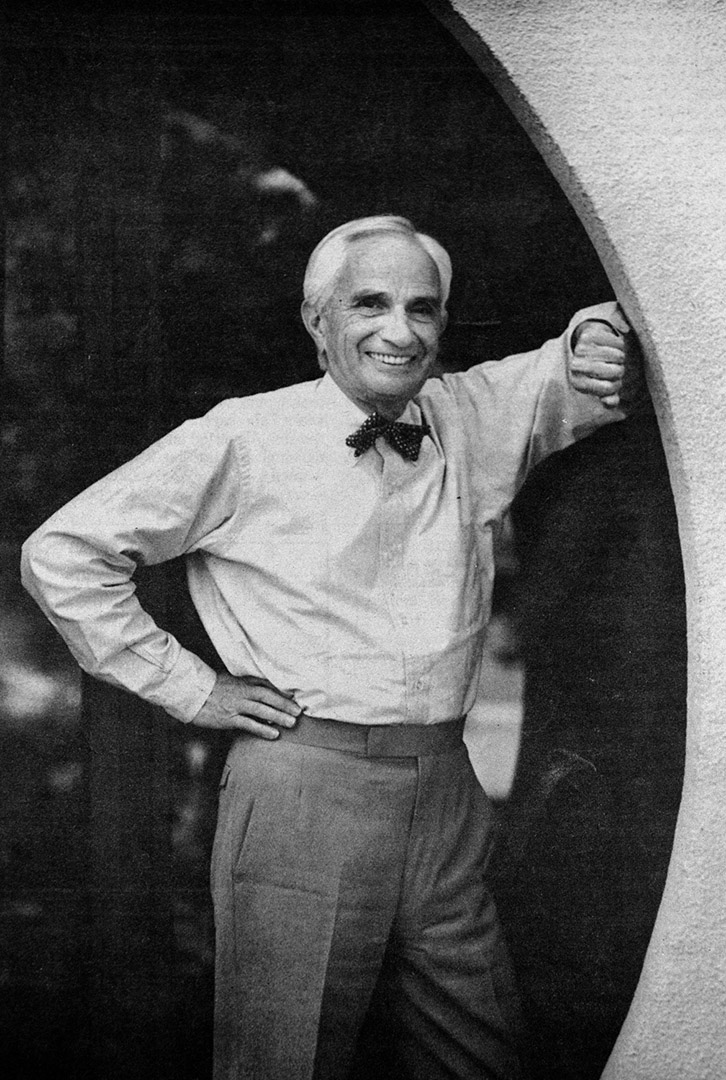

James Amaral ’80 poses at his Borealis Breads store in Wells, Maine, in 2008. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College).

Borealis shut down its retail stores in Waldoboro and Wells in March, but is preparing to re-open in mid-May with new social-distancing protocols. Amaral’s wholesale business was diminished but never halted.

“About 20 to 25 of our wholesale accounts [including Bates Dining Services] temporarily stopped taking orders, but all of our biggest accounts, including about 35 Hannaford stores, have continued to take orders.”

That’s kept his truck drivers and production staff fully employed. The furloughed retail staff is starting to come back to work.

For bakeries like his, there’s plenty of flour to be had. It’s the same product, but coming through the wholesale market, and delivered in bulk packaging (too big to be wedged on any grocery shelf).

“We haven’t seen any shortages at all,” Amaral says. With some bakeries closed, he says, if anything there’s probably more available on the wholesale market. “I’m sure there is an excess of flour sitting around in 50-pound bags.”

Before the two retail locations closed, when flour demand had already started to soar on the consumer market, Borealis Breads employees started digging into those giant sacks of flour and bagging up 5-pound parcels for retail customers. Amaral advocates for homebaking; it’s no threat to his business and a good thing for any household, particularly right now. “It’s one more great thing to do with kids.”

He co-authored a book last year, Borealis Breads: 75 Recipes for Breads, Soups, Sides, and More, and in recent weeks there’s been an uptick in sales. He adds, “I have certainly had a lot of people reaching out to me saying ‘What do I do with my sourdough?’’”

“The feel of dough is really soothing and therapeutic,” Reid says. “There is nothing better than a warm loaf of bread. It’s so enticing and rewarding. And everybody is stuck at home anyway.”

In fact, that trend-within-the-trend is one reason Reid has been so busy. An extraordinary number of bakers are going straight to the bigger challenge of artisanal breads made with sourdough starter, which leavens bread with “wild” yeasts rather than the commercial, packaged yeasts that have been in such short supply during the pandemic.

Unless the baker is lucky enough to get a good sourdough starter from a friend, they have to “raise” it on their own. It takes a lot of time, patience, meticulous measuring, and flour.

During that process, a starter requires flour and water to invigorate and strengthen it. Some recipes demand three “meals” a day for this growing starter, and after they serve their purpose, roughly 80 percent of the starter is removed (dubbed “the discard”).

Pampering a starter is a lot harder than opening a packet of yeast. “Kind of like the Grand Canyon” of baking, Reid says, “where you are leaping across into new territory.”

Novice sourdough bakers have questions. Engagement spiked on King Arthur’s website, which is when Reid raised her hand to help produce more content, including tips about keeping starters alive.

“People worry, ‘What if I kill it?’” she says. Usually her answer is, unless you see red, or streaks of orange, indicating bad bacteria, it’s probably fine. On a typical busy day pre-COVID-19, the King Arthur Flour website might have 600,000 unique visitors. Now? “I think we hit like 956,000 in March and it hasn’t let up.”

“Americans are so extreme,” Reid says with amusement. “They think, ‘If yeast breads are good, sourdoughs are even better.’ They also think they have to maximize their time. ‘I have all this time. I have to do something with it.’”

For some, the business of throwing out those leftovers, known as discard, is a cause for guilt, especially because flour seems to be in short supply. That’s where those English muffins come in. Like many of the recipes coming out of Reid’s kitchen in these pandemic months, the English muffins are meant to show how bakers can use discard.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_90ayojzTQ/

“We have like 35 to 40 recipes to use your sourdough starter,” Reid tells her viewers. “You can put it in almost any recipe that has flour and liquid.” (Pro tip: It’s also great for the compost heap.)

“There’s no sign of it slowing down,” Reid says, referring to the home baking trend. “Even if a switch got flipped, we would probably still have these people in our universe.”

She believes nothing since World War II has presented this kind of challenge for America. Many Americans are likely to stick close to home for months, even years to come. “How do you plan for that? How do you plan for this world now?”

Baking is a way to feel you have some mastery over your world, Reid says. The only problem? Amidst too much of a bad thing, baking presents too much of a good thing. Those English muffins are headed out of her kitchen, just like the muffins, breads, and five cakes she made last week for demonstrations. The beneficiaries will be her friends and neighbors. “I’m doing lots of porch drop-offs.”

Then she’ll make a chocolate cream pie.