Before dawn on Monday, unseen by most members of the campus community, mechanized forces executed something like a military pincers movement at Bates.

Objective: Dana Chemistry Hall.

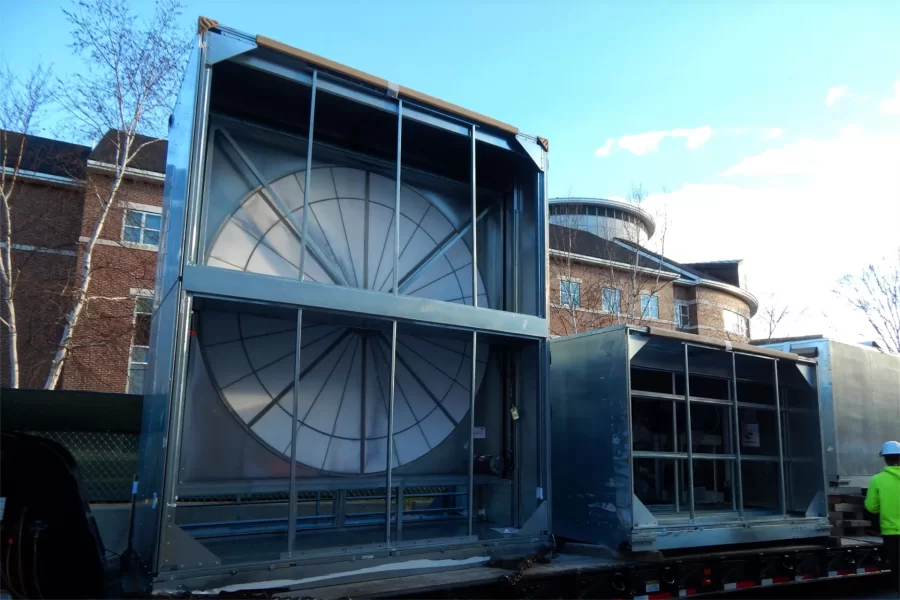

But this was no invasion. (It’s just that we’ve always wanted to write military history.) Instead, the occasion was the delivery and installation of new HVAC machinery that will heat, ventilate, and air-condition Dana for the foreseeable future. The operation was a major advance in an in-depth transformation of the building that began in July and will continue through next spring.

A hydraulic crane belonging to The Cote Corporation of Auburn approached Dana via Campus Avenue and the service road that crosses the Library Quad. Meanwhile, three flatbed tractor-trailers took the direct route, from College Street down Alumni Walk, where they parked inside the construction-site fence to keep truck activity separate from foot traffic (and skateboarders, cyclists, etc.).

Two flatbeds carried the seven major components of the HVAC machine, aka air handler (including the somewhat miraculous enthalpy wheel that we described last month). The third conveyed the equipment that Cote staff needed to hoist and place the boxy, bare-metal HVAC pieces.

The early start accommodated a few hours of prep for the big lift. The mobile crane, a Grove product sold by Milwaukee’s Manitowoc Co., needed to be leveled and blocked for stability. This was even more important than usual because the crane was sited partially on the slope descending from the Historic Quad to Alumni Walk.

In addition, trucks and individual air-handler parts had to be shifted around so that the parts could be placed into the building in the correct order.

In the jargon of rigging and heavy lifting, it’s called “picking” when a given load is attached to the crane and lifted. So the picking (and hopefully grinning) commenced around 10:30 a.m. and continued into early afternoon.

In addition to Cote and Bates personnel, people on the scene came from Warren Mechanical, the Maine firm that will actually assemble the air-handler and get it running; and Consigli Construction, which is managing the Dana project for Bates.

The air-handler takes up about half of the attic, east of the elevator shaft. The pieces came in through a big hole facing Hedge Hall that was made even bigger for this operation. (The hole, Dana’s once and future HVAC air intake, will be smallified later.) The installation process, in brief, was that first, the crane would float a given part up to the hole while workers on the ground handled lines to steady the load.

Then riggers would fasten cables to the piece and winch it into place on a frame of steel beams. Metal rods were used as rollers under the HVAC components.

It was a tight fit for a few units, including the one containing the enthalpy wheel, notes Bates Project Manager Chris Streifel. “There was just an inch and a half” of clearance for the biggest pieces. One of them rubbed on the ceiling as it came in.

“They had to go to a smaller rod,” he says. “They had three-quarter-inch rods that they were rolling it along on, and they had to go down to three-eighths of an inch just to give themselves that little bit of extra room to clear the ceiling and get it all the way down to the end.”

The load-in was finished by 2 p.m. or so. “Then the next thing will be to start connecting all of the different ducts and pipes and wires and controls, and everything else that goes to it. That’ll be the story the next several months,” Streifel says.

Some tooths: On other fronts (once you get started, these military metaphors are hard to avoid), “we’re at that steady-state portion of the job, where things are going to look the same for a while. All the same things happening on all floors,” says Streifel. “There’s a lot of progress, but it’s a little bit hard to see it.”

The second floor remains the exemplar, as work is furthest advanced there. For example, that’s where the hanging of wallboard has begun — albeit just at the tops of metal wall studs thus far. Called “firetops” because their use is embrangled with municipal fire codes, these board sections share space with utility runs and therefore tend to be placed just prior to those runs.

“They like to do them first,” Streifel explains, because it’s easier to cut openings in wallboard for pipes and wires than “to try to fit pieces around them.”

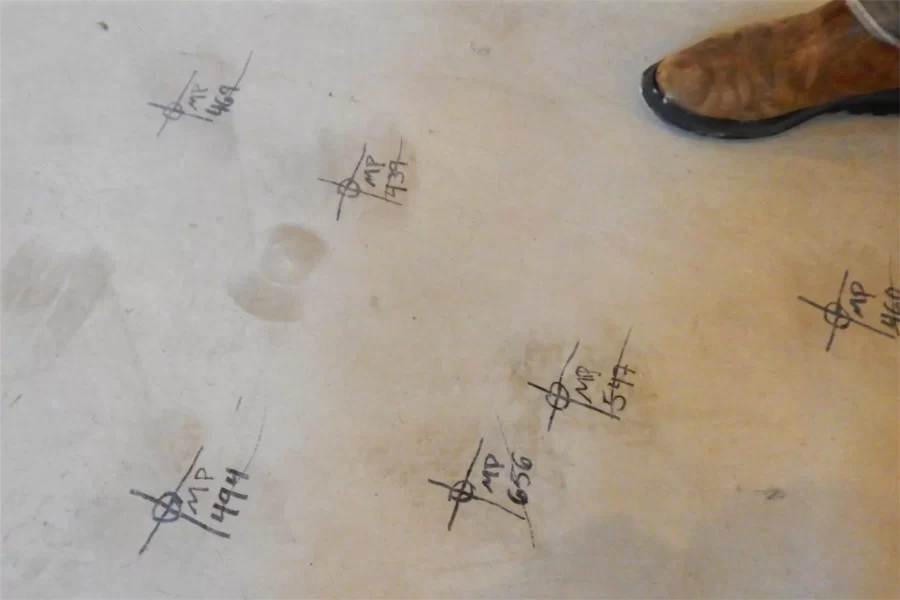

Speaking of things mechanical, electrical, and plumbical — sorry, plumbing-related — we were touring Dana’s ground floor with construction administrator Jacob Kendall when we spotted cryptic markings on the concrete under foot. Kendall explained that the lines, letters, and numbers indicated where MEP fittings would be placed…on the ceiling above.

A self-leveling laser pointer set upright on a floor mark, he said, would light up the spot overhead where the fitting would go. And this speaks to one of the differences between constructing a new building and revamping an existing one.

In a new building, it’s more expedient to place fittings while the floors are being fabricated. And you work from the floor above: That is, if you want to hang a pipe from a second-story ceiling, you initiate that attachment on the third-story floor decking.

In Dana or any other old building, though (not that Dana is just any old building!), it’s just more practical — thanks to the laser pointers — to use the second-floor floor, if you will, as a template for implanting MEP installations into the second-floor ceiling.

More practical, but not more agreeable. “You’ve got to cut the holes, you’ve got to drill everything out of the way, as opposed to just having it cast in place” when a new building’s concrete floor slab is poured. “It’s more time-consuming. It’s more challenging. It’s dirtier,” says Streifel.

“Then there are the nuances of dimensional differences. It gets a little bit harder to be as precise in an older building during renovation just because accuracy is more challenging to maintain. You can look and say, ‘I’ve got 9-foot-6-inch ceilings here,’ but in reality, it varies everywhere.

“You have to make certain assumptions when you’re doing the design and those don’t always hold true. You’ve got to be flexible to be able to adapt to that.”

In both new and old, anyhoo, the process for pinpointing MEP locations is the same, and somewhat amazing. As we’ve written elsewhere, those locations are first determined during the creation of a 3D digital model of the building. Then that model, combined with GPS and wireless communication technology, is used to guide someone in the physical building as they use surveying equipment to find and mark all the MEP points.

Other differences between renovating existing construction and building anew? In certain trades, renovations demand a certain amount of blending new with old, and making it all look new. For instance, a technique called “toothing” is conspicuous among the masonry work in Dana. This is where you bust out alternating blocks around an opening. (The result looks like teeth, but in masonry jargon they are tooths.)

So if you are filling an existing opening, you tooth around the opening so you can fit new blocks into the prevailing masonry pattern. If you’ve cut a new opening, toothing makes it easier to create a clean and consistent edge around it as you cut new blocks to fill the, er, cavities.

“There’s lots of construction [techniques] that involve the same concept as masonry toothing,” Streifel adds. A similar process will apply when the big hole in the Dana attic gable is shrunk and carpenters need to blend new wooden siding in with the old.

You even encounter it when new asphalt is laid next to old. “You don’t just butt them up together,” Streifel says. (That explains a lot about our driveway.) “On the old pavement, you grind it down and make almost a very thin set of stairs so that the new pavement butts and then overlaps and overlaps.

“That creates a joint that’s, first, more waterproof, and second, just stronger.”

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update loves to hear from you. Please send your questions, comments, and reminiscences about construction at Bates College to dhubley@bates.edu, with “Campus Construction” or “Does Homer Simpson know you’re stealing his material?” in the subject line.