If a medical doctor knows the right, proven technique to treat a disease, and an engineer knows the right, proven way to build a hurricane-proof structure, shouldn’t a teacher also use classroom skills that are backed up by research and evidence?

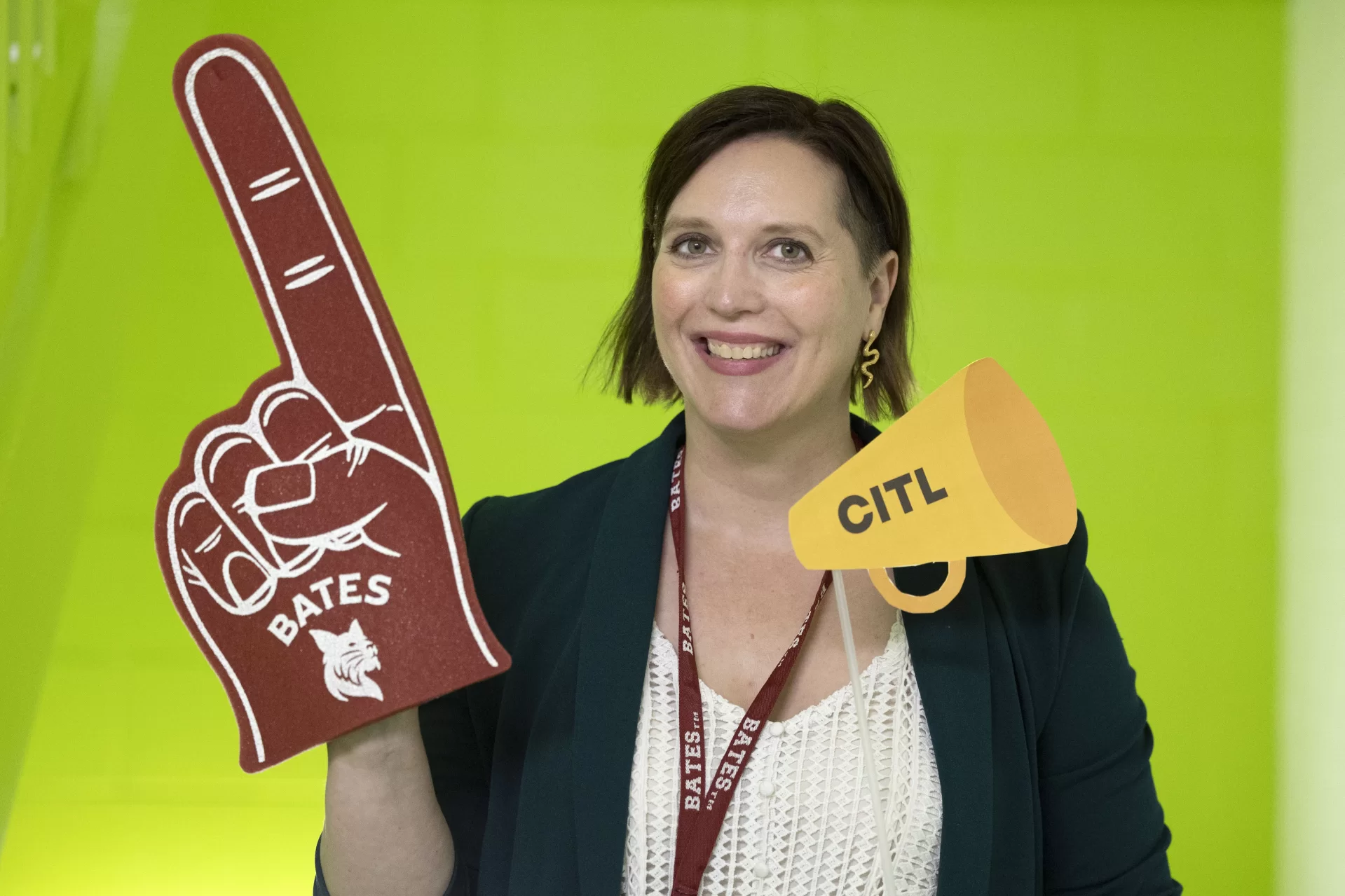

Absolutely, says Lindsey Hamilton ’05, a nationally regarded expert in the field of inclusive pedagogy, who arrived at Bates over the summer as the inaugural director of the college’s new Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning.

“Teaching and learning is its own academic discipline just like any other. It is a field backed up with scholarship and evidence: We know teaching is a skill just like anything else. We can improve it but we just have to do things that we know work.”

About the Center

Based in newly renovated Dana Hall, the Bates Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning promotes student success by supporting faculty and staff educators through ongoing professional development, including work in developing reflective, innovative, and inclusive pedagogies.

Twenty-one years ago, as a first-year Bates student, Hamilton recalls how she benefited from a teacher’s effective approach. She had convinced her first-year adviser, Paula Schlax, to let her take John Kelsey’s 300-level psychopharmacology course, with predictable results: On the first exam, she got a D “at best,” she says.

In grading the paper, Kelsey circled one of Hamilton’s lengthy but very wrong answers and wrote, “No — but you are thinking like a scientist. Come talk.” She did, and from that grew a mentoring relationship that continues to this day. (Kelsey is now retired; his colleague Nancy Koven now holds the John E. Kesley Professorship, endowed during the Bates Campaign.)

Kelsey’s act of encouragement was itself a small example of inclusive teaching. “He invited me into a conversation.” Without it, she asks, “Who knows what my future would have been?”

After successfully majoring in neuroscience at Bates and graduating magna cum laude with membership in Phi Beta Kappa, Hamilton earned a doctorate in neuroscience from Wake Forest, fully intending to become a research scientist.

But Hamilton, the daughter of two career high school educators, was always drawn to the study of teaching — known as pedagogy — specifically to inclusive teaching, which reflects the idea that there are proven ways to reach and teach more students, more effectively.

Working with the U.S. Army on defensive strategies against chemical warfare agents, she got involved in and inspired by first-responder training. “It was literally life and death. We had to make sure they understood what to do and why,” she says.

In 2013 she joined the faculty at the University of Colorado, where she emerged as a university leader in inclusive teaching and learning, advancing strategic priorities related to student success, innovations in teaching, and creating inclusive cultures, becoming the director of the school’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning in 2020.

We talked with Hamilton recently about her path to Bates, from Bates, and back to Bates, and how she hopes to make the Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning a distinctively Bates program.

Your parents were both high school teachers. Did that affect how you approach your work today?

People talk about it like teaching is in the blood, right? One of my parents’ earliest memories of me is me using one of their old grade books to set up a classroom for my teddy bears, and having teacher–teddy bear conferences.

The dinner table conversation was always about school. My brother and I were talking about what we were doing in school. My parents were talking about what they were doing in school. I think that teachers do love talking about teaching and learning. You go into the field of teaching because you love learning and you want to continue to do that. It never stops.

You tell a cool story about your office in Dana Hall being the first faculty office you ever stepped into.

It belonged to Paula Schlax [now the Stella James Sims Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry]. She was my First-Year Seminar professor and adviser. The course was “Epidemics: Past, Present, and Future.” Who knew it was going to be so relevant 20 years later? Being here feels like a full-circle moment.

She was what drew my attention back to Bates. I saw Paula at a conference related to the HHMI inclusive excellence grant that Bates has. It was a virtual conference, so I saw her name and I messaged her and said, “You probably don’t remember me…” And she said, “Of course I remember you!”

And we started chatting and catching up. When she realized that I was the director of a teaching center at the University of Colorado, she said, “Do you want to come do a lecture here at Bates? Do a seminar for us.” And I said, “Absolutely.” After the lecture, I remember going home that day and talking to my husband and saying, “What do you think about Maine?”

When John Kelsey marked your paper by saying, “Come talk,” is that an example of inclusive teaching?

It’s a growth mindset moment. It is inclusive in the sense that if he had just written, “No, this is all wrong,” who knows what my future would have been. I may have felt so dejected that I didn’t major in neuroscience anymore.

But instead he invited me into conversation and coached me on how to prepare better for that course. He did not change his standards at all; his standards were very high. You had to work to get things correct in his class. And so maintaining that high level of rigor but doing so in a way that invited students into the conversation, into participating. And his mindset was, of course, anyone can do well.

That’s the message Bates is trying to send today: If you want to do something, you’re here and you’re set up to succeed. Did you feel it from other professors?

Absolutely. I think a liberal arts education has always been about discussion and writing and teaching you how to think, more than, “Here’s the answer and this is how you find the answer.”

I took a Short Term course from Charles Nero [now the Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Prof of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies] that looked at Whoopi Goldberg movies and television shows. And I remember thinking that it was just going to be a fun course. But to this day, it’s probably the course I reference the most in some of my own teaching practices. He really inspired us to make connections very broadly and encouraged our interests — what we were interested in doing and pursuing.

I wrote a final paper on the hyenas from the Lion King because Goldberg voiced one of them. I brought in endocrinology neuroscience and hormonal patterns, which can make female hyenas very masculinized. I was able to connect the world I was most interested in, neuroscience, to this course and make the connections and see how it played out.

I told Charles that when I saw him recently, he was like, “I can’t believe you still talk about that.” I told him that I use it as a whole slide when I teach endocrinology!

You earned a doctorate in neuroscience at Wake Forest, then worked as a behavioral toxicologist for the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense. Your LinkedIn profile says that you worked on the “safety and efficacy of chemical warfare nerve agent medical countermeasures.” Was that intense?

Yes, it was intense. Syria was thought to be using chemical weapons at the time, and we also analyzed chemical weapons used in Iraq previously. It was very different from anything I had been doing. But honestly, that’s where I found my love of teaching again.

I had moved into research. I was going to be a big scientist. My parents were like, “You know, you always loved teaching.” I’d say, “No, no, no. I’m a researcher, I am a scientist.” When I was with the Army, we were doing a lot of first-responder training for what happens if there is an attack. I started participating in some of those workshops and trainings.

And it was very striking to me: This was literally life and death. I had to make sure they understood what to do and why. Because if you mess this up, somebody is going to die.

It had me thinking about what is the best way to convey information. And then I found myself moving away from the bench and wondering about the research on how people learn.

One teaching style at that point was probably death by Powerpoint. What were you seeing that caught your eye about teaching a group of first responders that said, okay, we can do this better?

This is not a knock on the military, but their presentation style is very boring due to the emphasis on efficiency: “Here’s a list of bullets on the slide and let’s move on.” You can see people’s eyes glazing over when that’s happening.

The training was somewhat hands-on already, and we made them more hands-on. We wanted people to practice under circumstances where there’s pressure: doing a case study, role playing, moving through it, applying information. I can tell you the signs of exposure to a chemical warfare agent, but that might not be enough for you to really understand the signs.

So we had them watch a video where signs of exposure show up and progress. They were given a stopwatch to pinpoint when they see the first symptom. So they have to see it, engage with it, and be accountable. It’s your number vs. my number, and you have to tell me the right number.

So let’s talk about inclusive teaching and learning. Do you have a pat definition of what inclusive teaching and learning means to you?

I would say it’s not a checklist, which is a question I get a lot: “Okay, just tell me how to do it. What do I need to do to be an inclusive teacher?” It’s great that people are interested, but there is no magic bullet. There is no one best teaching strategy but a lot of different effective strategies that we know about, and we have to find the right ones for the different contexts people are teaching in.

Inclusive teaching is really more of a lens that people should apply to all aspects of teaching: course design, learning objectives, materials, activities, and assessments. All those practices have to be viewed through that lens: “Are people being invited in? Who’s being left out?”

Are we naming something that has always existed in a sense?

There is a little bit of, “Why now?” The answer is that this is an important moment — our society is at stake. We’ve always known inequities exist in our society. I think the pandemic has really pushed it to the fore and made healthcare inequities, technology inequities, and educational inequities so much more apparent. They’ve always existed but now we’re seeing it and we’re willing to do something about it, trying to address it.

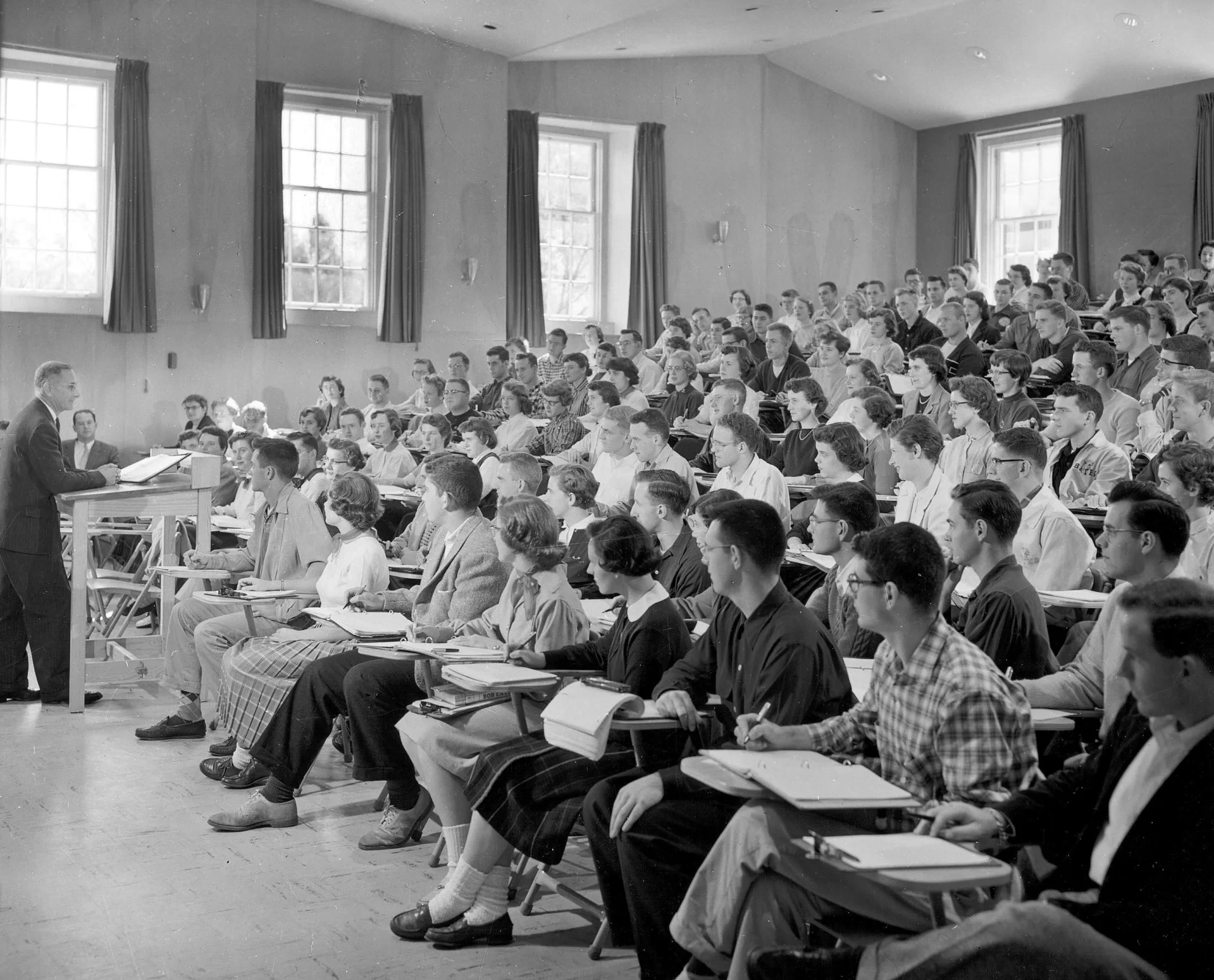

Traditional pedagogical methods, whether it’s death by Powerpoint, or the sage on the stage model, where a faculty member lectures for however long the course period is, and students frantically write everything they say, are based on the idea that students are empty vessels waiting to be filled.

We know that those traditional methods, traditionally applied, don’t serve all of our students and we can’t counter structural inequity with good will. We have to be intentional about it. It’s not enough to say, “We want to do better.” We have to intentionally build it in.

So is the sage on the stage gone? Or can you be a gifted lecturer and be an inclusive teacher at the same time?

We know active learning works better than passive learning for people. And the sage on the stage, those traditional methodologies, tend to lean towards the passive. Students were writing down word for word what someone was saying. The thing is, students perceive that they learn more through a lecture than through active learning — but actual learning is higher with active learning.

You can be a great lecturer and a gifted lecturer, but you want to also encourage the students to be thinking.

There is information that has to be conveyed, and lecture is often the best way to do that for some content. And so I never want people to think I can no longer lecture anymore. If you just went to a class and were doing activities constantly for 12 weeks, that would be exhausting. for everyone! And probably not the best use of our time.

So it’s more about bringing in different modalities for learning: multiple methods, multiple approaches. You’re providing a lecture but you’re also asking students to respond to it. Maybe they do use a classroom assessment technique and after you do a 20 or 30 minute lecture, you have the students work in groups on a case study related to that, you’re applying then what you’ve learned.

You gave a fascinating tip in your newsletter about how professors can get students to be more engaged in their outside reading by creating structured reading groups. Students are not only assigned a reading but given a role they will play during small-group discussion of that reading during class. It seems so simple!

The structured roles give each student something to focus on as they’re “doing” the reading. And that’s why I led with it in the newsletter: I’m strategically, intentionally putting forward some of the best bits — these are surefire wins — because I want Bates people to do it, feel great about it, and come back for more.

Then we can get into some of the harder stuff or that we might have to play with and it might not go well and experiment more.

What is the message to alumni and parents who have their own idea of what effective teaching is from their own experiences?

This is the future of teaching and learning: We have to be thinking about inclusion. And so for other alumni: Think about all the great experiences and if those could be elevated for future students. Think about maybe your not so great experiences, if those could be minimized going forward. We don’t want anyone changing their major just because they had a bad experience in a course or didn’t do as well as they wanted to.

Some say that inclusive teaching strategies lower the rigor of a course.

The question comes up a lot. But no, we are maintaining the rigor and, in fact, what we’re doing is we’re maintaining the high bar and we’re helping more people reach it using proven tools.

Think of a ladder as the metaphor. You could have huge spaces between the rungs, traditional methodologies, and some students are going to make it to the top. But if we put in more structure, it doesn’t hurt anyone. The students who are already making it are not going to be impeded. We are now simply making the opportunity there for more students to meet the bar.

There’s a wealth of literature showing that inclusive practices and teaching do not harm students that would’ve done well in the traditional kind of methodologies anyway.

You have monthly workshops, and the one around Halloween was “chilling teaching tales.” What did you want to accomplish with that topic?

I wanted to make it fun and make it feel like an invitation. I don’t want to be, “Let me tell you what to do.” I want the center to be a place where we can share some stories and strategies together.

So we shared a bunch of teaching horror stories that I had gathered from friends and colleagues everywhere. And I threw in some of my own. It’s easy to feel connected to people when you’re laughing — or gasping in horror at some of the stories like, “Oh no, I’m glad that wasn’t me!” So you’re creating community and commiseration. Teaching can be hard and we sometimes need a little commiseration.

I was so pleasantly surprised to see how many people were willing to be vulnerable and sharing, “This is what happened to me my first year teaching,” and then saying, “That’s why I don’t do it this way,” or “These are things we can do about it.”

I’m learning that the course evaluations by students are problematic, even as they are supposed to improve teaching.

Yes. We know quantitative courses are evaluated more harshly than non-quantitative courses. We know non-elective courses are evaluated more harshly than electives. We can’t mitigate against that.

We also know various factors that influence the evaluations, like bias, implicit or unconscious. Gender, race, ability status, perceptions of how well you meet the picture of what they view in their mind as a professor. And those biases are the things we can mitigate again.

So there’s evidence and literature that if you talk about that unconscious bias with the students before they fill out the evaluations, it reduces the gender bias. It hasn’t been evaluated across other measures yet, but we think that it would help.

We’re in a culture where you can review anything. So people, probably to the detriment of teachers, are in the habit of giving scathing reviews.

It’s easier to criticize than to praise.

I’ve been doing these group instructional feedback techniques for the midterm assessments. So it’s a GIFT — Group Instructional Feedback Technique — because it is a gift to get feedback from your students. So there’s value in saying to your students how much you appreciate their feedback and that it is wanted and it is appreciated. Then they tend to take it more seriously.

But they have to know that it’s going to be used. If their feedback goes into an end-of-semester void and they never hear about it again, they don’t feel like their voices were really heard. And so it becomes very easy to just get negative with everything.

Whereas, it’s more effective if you’re asking for feedback all along in the whole semester and showing that you’re willing to listen and willing to say, “I made my decision because of this” or “This is why I’m using this pedagogy in this course.” People get it; students understand.

Bates is doing work to make its teaching and curriculum in STEM fields more equitable. What do you see as far as their work?

They’ve done some amazing work in terms of rethinking curriculum, putting more active learning into the curriculum especially. I think at this stage, we need to be shouting this from the rooftops for everyone to hear. It’s not that the work is done; there’s always more work to be done. I’ve been in this field for a while, and they’ve really accomplished something great.

There’s a true/false quiz on your whiteboard that makes statements about what is and isn’t effective teaching. What’s the message you want to send with that quiz?

That there are a lot of misconceptions about effective teaching. And the quiz shows that I like having some fun; it speaks to my approach to things. There’s a whole literature on playful pedagogy: People learn better when they’re having a little fun. And so why would that not be true for educators as well?

You didn’t put up just a true and false, but with footnotes to sources. Why?

It’s about evidence. I want to underline the fact that this is an academic field, there is scholarship around this. There is evidence: we know teaching is a skill just like anything else. We can improve it. We just have to do things that we know work.

And sometimes it’s counterintuitive. Some of the tactics that we think should work, or that worked for us as students, don’t actually work for the bulk of people.

What is the faculty’s reaction to your offerings?

I’ve been welcomed very enthusiastically, and I think there’s real hunger for more conversation and a place for that. The faculty are doing some amazing things. I’ve had the opportunity to go into a number of classes and do some observations and midterm assessments. More than once, I’m thinking, ‘This is so cool. I want to take this class!” We have a lot of people doing amazing work in their own area but not having the opportunity to talk broadly about it. So I see the center’s and my role as elevating what’s going on, and being a hub where I can help make connections.

There’s the Maya Angelou quote, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better” If we learn more, we’ll move forward. I want to invite people in and say, “It’s okay. This is a learning opportunity.”

Faculty, and especially faculty here, love learning and teaching. They want and welcome opportunities to discuss teaching with their colleagues, but they don’t always have the time or space to do so.

There are centers for teaching and learning at other colleges. What would be the Bates version of that?

Going back to our tradition of being inclusive, we’re naming something that was already here and putting our intention behind it. We’re saying that inclusion is going to be baked into every educational experience.

For Bates’ Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning, the differentiator is that we are inclusive of everyone. So I don’t want to see this as a purely faculty-facing institution. Many staff are heavily involved in the education process. The center is for them, too. Students, too, can be very valuable pedagogical partners in sharing their insights and experiences.

It’s everyone coming together. So building that in intentionally. A lot of teaching centers are modeled after very large institution teaching centers at large universities, and they’re doing huge volume. At Bates, we can take advantage of our scale and the connections we are able to make, like going into Commons and being asked, “Hey, you had a big exam. How’d you do? Are you feeling good?”

I remember those personal connections from my time as a student here and those are what make Bates special. And I want the center to represent that.