An osprey is the Greg Louganis of the avian world. Capable of diving head-first into the water from high in the sky, this raptor repositions its body along the way, snagging a fish with a feet-first splash and grab.

In the warm months, ospreys are frequent visitors to campus. They circle Lake Andrews, searching for their next meal, then dive into the Puddle to scoop a fish (there are lots of goldfish in the Puddle).

But that immense talent doesn’t mean that an osprey, or any bird, will also be good at nest-building, or will make good choices about where to build a nest, says Don Dearborn, an evolutionary biologist and professor of biology.

Watch this osprey bring a branch, gripped in its talons, to the top of a light pole at Garcelon Field on April 7, in an attempt to build a nest.

During the first week of April, an osprey, having returned to campus after its winter sojourn, presumably to Central or South America, tried to build a nest in a spot that seemed to meet the three rules of home building for humans or birds — location, location, location.

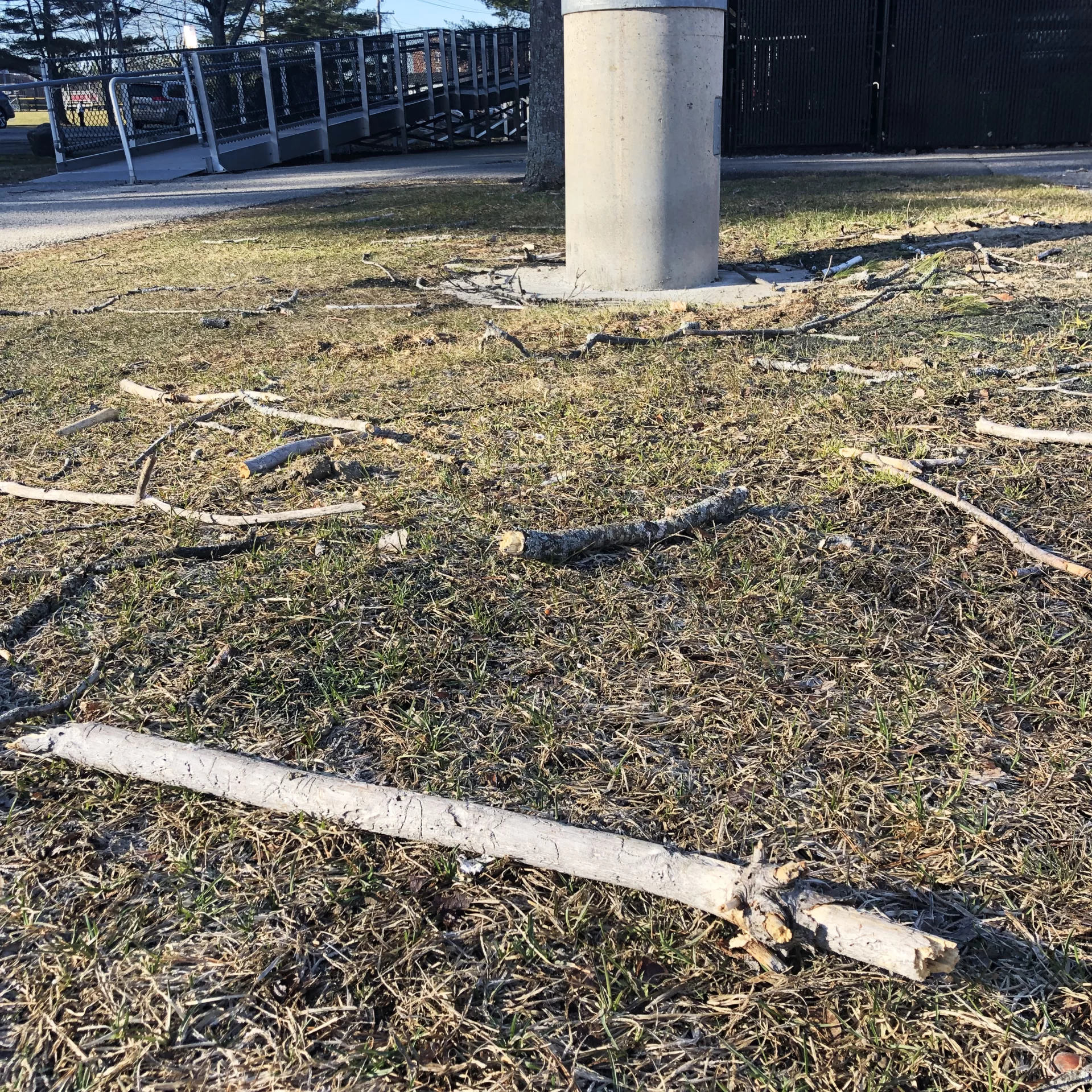

Yet the effort failed. Over and over, the osprey carried sticks to Garcelon Field, placing them atop a light pole. But the ever-growing pile of sticks that fell to the ground told the tale: There wasn’t enough purchase or flat space atop the pole to build a nest, and the sticks fell, or were blown, to the ground. The osprey eventually gave up.

“Birds can choose poor sites or simply be bad nest builders,” explains Dearborn. “Although some species are incredibly talented nest-builders, others make nests with holes in the bottom that eggs drop through.”

Birds that live in human-modified environments face additional challenges for nesting, Dearborn explains. “Urban ducks, for example, can choose locations that are fine from their perspective but ultimately problematic.”

Last summer, a duck decided that a planter in front of busy Pettengill Hall was the place to nest. From the duck’s point of view, the location was fine: close to water. But though folks from Bates Facility Services worked to keep folks clear of the location, the duck did not hatch any ducklings. Another duck nested in a tree on the Historic Quad.

There’s also nest-building drama and outright thievery, Dearborn says. Frigatebirds, for example, don’t have the right anatomy to collect nest materials, like twigs and sticks, on the ground. “Their legs and feet are too short to do much walking.”

So they often purloin nesting material from other birds’ nests. “They also steal material in mid-air from other frigatebirds,” says Dearborn.

“But regardless of how frigatebirds acquire nesting material, they share with the duck and osprey the crucial task of making an effective nest in a good location,” he says.

A task that evidently, in the case of our local osprey, doesn’t always go well on the first try.