On a 22-degree day in November, Erin Reed ’08 arrived at the Trinity Jubilee Center in Lewiston at 5:30 a.m. to help unload some 4,000 pounds of food from a Good Shepherd Food Bank truck.

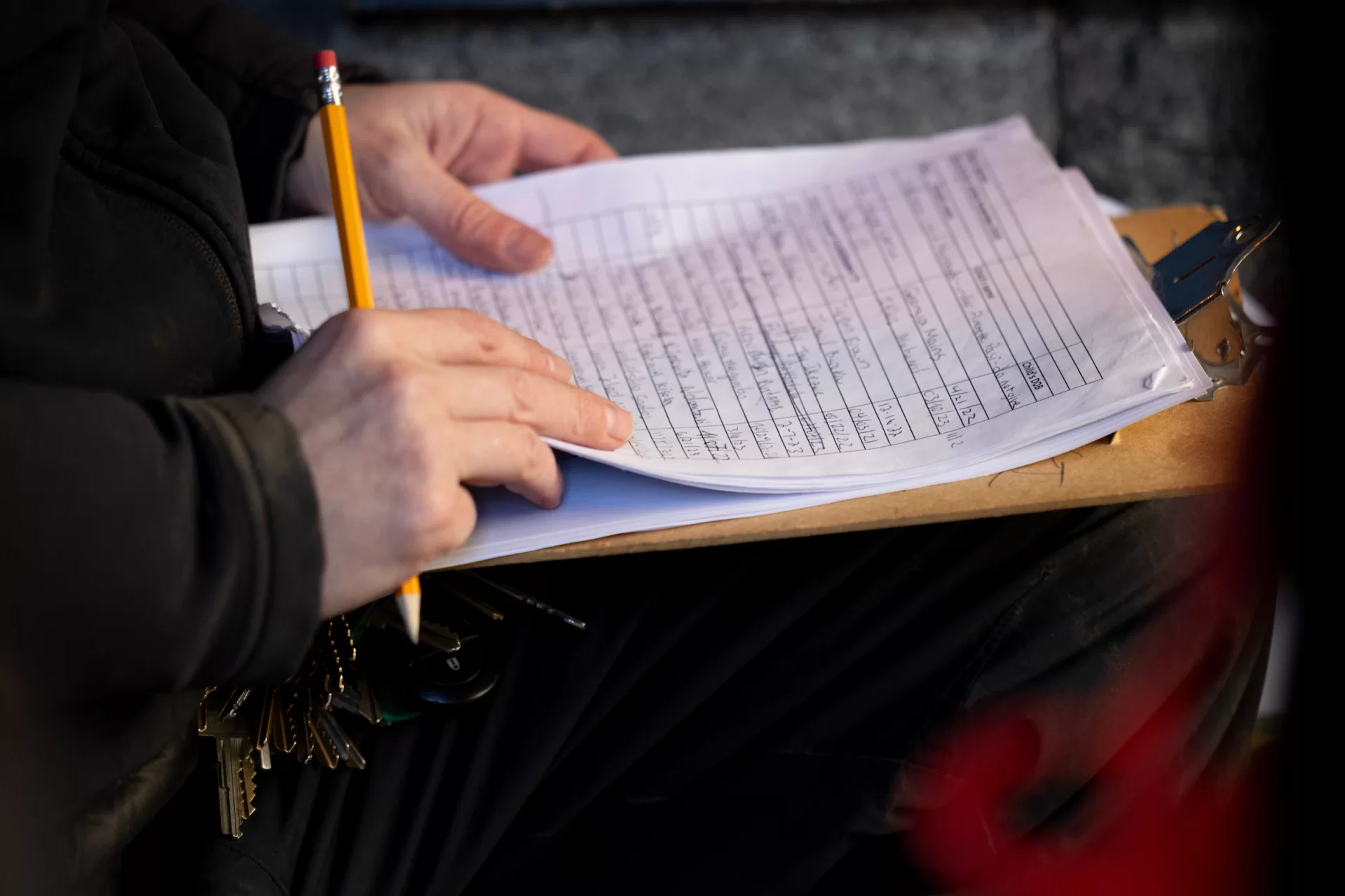

Two hours later, bundled in ski pants and a hoodie, the center’s executive director stood outside, patiently checking in people who came to collect cardboard boxes full of free vegetables, fruit, cheese, and frozen catfish to help feed their families.

After another two hours, Reed finally came inside the soup kitchen to work on her laptop. She looked around for somewhere to sit, since a doctor was using the center’s only office to provide free health clinics. She grabbed a metal chair and set up shop in a large hallway where grocery boxes were being packaged, her lap serving as a makeshift desk as she typed away. It proved the perfect setting.

Behind Reed draped over a large stack of diapers hung a blanket adorned with rainbows and unicorns — a backdrop that stood in stark contrast to the difficult, life-altering social work Reed does here for those in need.

“I’ve watched the impact of what Erin has done and what the place has meant to Lewiston as part of the fabric of this community,” said Kim Wettlaufer ’80 of Lewiston, the former director of Trinity Jubilee Center, who is still an avid volunteer. “There are a lot of demands. People come here with extreme circumstances. Their needs are great. It needs someone who is even-keeled, someone with a calm exterior.”

Reed is all of that, but her job is far from easy. So for the ongoing What It Took series, we asked her where she finds inspiration, strength, and the will to dig deep on the darkest of days.

What did it take for Reed to serve the most vulnerable in our community in the early days of COVID when all of her volunteers suddenly quit because of the public health crisis, or following the Lewiston mass shooting during the shelter-in-place order, or during any one of Maine’s frigid winters the past 10 years?

When asked, Reed’s words evoke the idea of compassion, an awareness of the needs of others, and the desire to help those in need.

“I think of the quote ‘To whom much is given, much is required.’ To me, I’m someone who was born in the U.S., I’m healthy, I have a solid family. All that puts me ahead of 90 percent of the people in the world. I don’t know how, when you work in a place where everyday you see life is way more precarious than we like to think, how you don’t help,” Reed said.

Part of that compassion comes from the fact Reed’s grandparents were Irish immigrants, coming to the U.S. from County Cork and County Tyrone. In Detroit her grandmother worked as a domestic worker and her grandfather at a manufacturing job in the auto industry.

“The reality is no one else will do this. No one else will cook lunch for the community every day, no one else will do paperwork to get kids out of refugee camps. What we do is not fun or easy but we can’t just walk away,” Reed said. “It’s hard to go home at the end of the day. My clients can’t get jobs until I help them get a work permit. If their landlord is asking for a rent check and their kids are hungry, an hour of my time could change their life.”

Since Reed took over as the center’s executive director in 2014, she’s grown the center’s reach, increasing the staff from one to four full-time employees and the number of families the Center’s Food Pantry helps feed each week from around 100 to upwards of 200. The center now helps an average of 100 people a year find jobs and it annually serves a total of 4,000 individuals in the Lewiston area.

Moreover, next month Reed will announce the final stage of a fundraising campaign for the center’s new home after the nonprofit raised more than $2 million to build the 5,500-square-foot, $4.9 million center that will be located downtown on Bates Street. [March 2024 update: The center has now raised $4 million, more than 80 percent of the project budget.]

When it’s built next year, the work of providing a food pantry, soup kitchen, day shelter, and resource center will move from the basement of Trinity Episcopal Church, where the nonprofit has rented space since 2001.

“She’s taken it to a whole new level,” said Wettlaufer.

Part of what led Reed to find her work at the center were her years at Bates, before she graduated with a degree in sociology in 2008.

Reed found the Trinity Jubilee Center within 48 hours of arriving on campus when her AESOP trip went there to volunteer in the soup kitchen. Afterward, she would ride her bike down to help at the center in whatever way she could. Then she served the Harward Center for Community Partnerships as a student volunteer fellow, coordinating Bates volunteers at the Trinity Jubilee Center.

Reed still works with the Harward Center, guiding student volunteers and those looking to job shadow. Darby Ray, the Harward Center’s director, called Reed a “transformative leader.”

“The culture on campus was that if you were excited about something, go for it. That was a great mindset to send us out into the world with.”

Erin Reed ’08

“She’s amazing not only because of the impact she and her team have, but because they are profoundly relational and humble. There’s not enough of that today,” Ray said. “Erin is one of the most humble and understated leaders in our community. She’s not about the fanfare or the attention. She’s about supporting the vulnerable members of our community.”

Reed said the Bates philosophy to try, explore, and adventure inspired her to believe she could do anything she wanted. She belonged to nine clubs and organizations at Bates.

“It was amazing being around people who were so curious and so engaged. The culture on campus was that if you were excited about something, go for it. Learn all about it, get involved, don’t be intimidated, just jump in. That was a great mindset to send us out into the world with,” Reed said.

But when Reed reflects on her time at Bates, she also calls her younger self naive for how she tried to help the world simply by joining in protests for social justice causes. In the end, it was a single fundraiser her junior year that showed her a better way.

A friend who worked in Commons was helping to fundraise for another Commons employee who was getting treatment for breast cancer. Reed joined the effort, helping to organize the sale of homemade fudge outside Commons to raise money for the sick woman. Not long after, while studying at a table in the dining hall, she looked up and saw the young mother whom she was helping, whom she had never met.

“She was still pretty sick. It was so sweet watching everyone come from behind workstations and fuss over her,” Reed said. “It really drove home to me what matters: Helping out other people in your own community. You can make a big difference by putting your energy there.”

Almost 20 years later, Reed lives that experience every day. Now it’s difficult for her to go shopping at Home Depot or the grocery store. Everywhere she goes, she sees people the center has helped.

“Going shopping can take a very long time,” she said with a laugh. “In every department there is someone who we helped get a job. They are so excited, they want to thank you. They want to tell you about their kids. That’s been a constant for years.”

In the end, what it takes for Erin Reed to charge into a 12- or 14-hour work day — an all-too common experience for her — is knowing herself and the kind of meaningful work she needs to do, work that embraces our shared humanity.

“This is my place in the world,” she said with a shrug. “I don’t know how I could get up every day and do something I didn’t really believe in. If people come and ask you for help, how could you say, ‘No?’”

As an example, Reed shared a story of a local man who is on oxygen and lives in his car. He regularly comes into the center and asks for help, handing over his oxygen machine to Reed or others on the center staff so they can plug it in and charge it for him, usually while they are busy helping other clients.

“He’s always very grateful. It’s a huge thing for him. He doesn’t have anywhere else to do that,” Reed said. “You don’t realize how kind and how resilient people are.”