In the greenhouse atop Carnegie Science Hall, a green seedling peeks up from an unassuming black pot. Small but storied, this plant has traveled the world to put down roots here in Lewiston.

The ginkgo tree seedling, not even a foot tall, is the child of a ginkgo tree in Hiroshima, Japan, one of 170 hibakujumoku or “survivor trees” that miraculously lived through the atomic bombing of Aug. 6, 1945 — 80 years ago this August — and still stand in the city today.

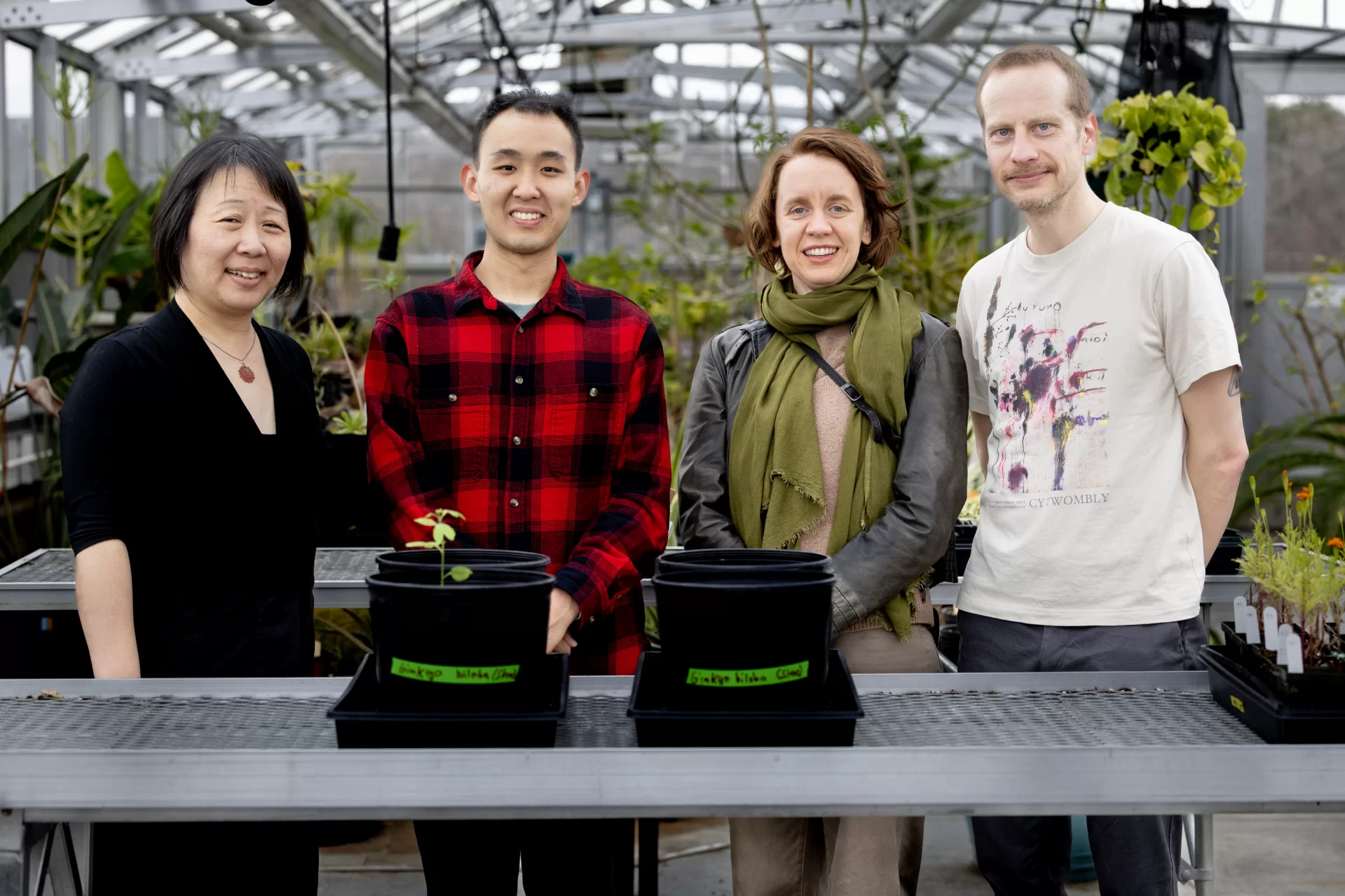

“We are looking at a piece of something that survived the bomb, and that’s what’s really magical,” says Alan Wang ’24, who coordinated the effort to bring the seedling to Bates in partnership with the heritage organization Green Legacy Hiroshima.

Green Legacy Hiroshima tends to the surviving trees in Hiroshima and their legacies, collecting their seeds and sharing them with institutions of higher education and botanical gardens. The offspring of the survivor trees are now growing at 146 partner institutions across 41 countries, bringing their message of hope and survival to communities around the world.

As a junior at Bates, Wang, who is originally from Henan, China, studied abroad in Japan through the Associated Kyoto Program. As part of the program, he traveled to Hiroshima to visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, where Green Legacy Hiroshima gave Wang and classmates a tour of the hibakujumoku.

From a watch that stopped exactly at the moment the bomb detonated, to a shadow created by someone instantly vaporized by the heat of the atomic blast, what Wang saw in Hiroshima left a lasting impression on him.

“You can just see the devastating impact that the nuclear weapon caused,” Wang says.

When he learned that Green Legacy Hiroshima had no partners in Maine, Wang became determined to make Bates the first. He imagined a survivor tree planted on campus, its presence encouraging discussion about the effects of nuclear weapons.

“I envision it as a platform to get people to talk about this,” Wang says.

But before he could bring the seeds to Bates, Wang had to secure the support of campus partners and then apply to join Green Legacy as a partner institution. Though it would be a long process, Wang was committed.

As a senior back on campus, he started by bringing his idea to Assistant Professor of Japanese Language and Asian Studies Hanna McGaughey and Lecturer in Japanese Keiko Konoeda, who were both eager to support Wang’s efforts. Impressed by Wang’s persistence, Raymond Clothier, the interim multifaith chaplain at Bates, also joined the project.

“When somebody is willing to dedicate that amount of time to a project like this and to not let it go when he encounters bumps on the road, it is inspiring,” Clothier says.

Finally, Wang was left with finding a biology professor who was willing to take on a multi-year responsibility. A young tree needs a lot of tending before it is sturdy enough to plant outside. Wang eventually connected with Daniel Slane, a visiting assistant professor of biology, who immediately agreed to help.

With the four faculty and staff members on board, Wang submitted the application for partnership to Green Legacy Hiroshima during the holiday break between semesters of his senior year and heard back within a month: Bates was approved as a partner.

In summer 2024, seven ginkgo seeds arrived from San Diego, where all Green Legacy Hiroshima seeds for U.S. partner institutions are stored. Slane first sanded their hard exteriors to make it easier for them to germinate. He then refrigerated two of the seeds for cold stratification, a process which mimics winter by exposing seeds to cool weather and encouraging germination. After a couple of months, he removed the seeds and planted them in pots in the greenhouse high above the Historic Quad.

But, those first two seeds did not germinate. Slane suspects that the soil conditions were too moist. Back to square one, Slane refrigerated and planted three more seeds. A couple months later, one seed germinated. Now, Slane heads upstairs almost daily from his office to check on the seedling.

One of the oldest tree species on Earth, ginkgo trees are known for their resiliency. Konoeda says there is a message there for all beings about enduring through the impossible.

“The mother plants survived and watched the experience — the fire and the wind and the heat. And still, we see this green and the tree,” Konoeda says. “So, we don’t know what is going on in the world right now, but we will survive.”

Bates’ seeds are from a 200-year-old ginkgo tree in the lush Shukkeien Garden, created in 1620. The garden is a little less than a mile from where the bomb exploded. Its blast spread outward and then the force of air, rushing back toward the hypocenter, pushed the tree inward, leaving the tree with a permanent slant toward ground zero.

The fact that the hibakujumoko are able to reproduce is impressive, Slane says, because high radiation can cause plants to become infertile. The ginkgo seeds’ DNA may even be altered due to epigenetics, the way in which heritable traits in offspring are changed by a parent’s life experiences.

“If you have seeds from a tree that has been impacted by a natural event or something like a bombing, they will have certain epigenetic changes that allow the offspring to probably deal better with those changes,” Slane says.

Though it will be at least two years before the tree is large enough to plant outside, the ambition, or hope, is that the ginkgo will eventually be planted on campus, joining the ranks of the bright yellow tree standing guard outside of Carnegie since 2003 and the new ones at Bonney Science Center. Once the tree is planted, Clothier and the Multifaith Chaplaincy will be in charge of maintaining it.

“It’ll be meaningful to me to see the tree when it’s in the ground, to have a place, a marker on campus for peace, for the intergenerational work of peace,” Clothier says.

Like the seeds themselves, each of the people contributing to this project have a personal tie to the atomic bombings or the brutal history of World War II, and most have traveled across oceans to end up at Bates. Konoeda, for example, grew up in Kitakyushu, Japan, the original target for the second atomic bomb. The city narrowly avoided complete destruction when clouds obscured its skyline on the planned day of the bombing, and American planes headed toward Nagasaki instead.

Growing up in Independence, Mo. — the hometown of President Harry S. Truman, who authorized the atomic bombings — Clothier interrogated the history of the bombings at a young age.

In middle school, he and his peers put Truman “on trial” for a school assignment, attempting to answer the question, was authorizing the bombings the right choice? Thinking through these questions in a shared hometown contributed to Clothier’s interest in peace and ultimately led to his anti-nuclear weapons activism.

McGaughey and Slane both have a German background, which instilled in them the importance of never forgetting the atrocities of the war. Both also spent years living in Japan.

Growing up in Germany, “I was brought up with, ‘Remember, remember, never forget what happened back then,’” Slane says. “For me, that’s in a way connected, and that’s why my heart is there.”

At the intersection of these varied identities and backgrounds are differing narratives about the story of World War II and the relationship between countries like Japan, Germany, and the U.S. The ginkgo trees do not declare one narrative right or another wrong, the project contributors say; they simply open up a space for listening and thinking beyond preconceived notions.

“Japan tells a story that is very much about its big victimhood and not about what it has done or how it has come to that position in the history,” Konoeda says. “And the U.S. tells its own narratives. And only by stepping outside of those stories, you see a bigger picture. And we are stuck now looking at this contemporary world that’s so divided in different ways, but we need to step back.”

As a living reminder of both the past and the potential of the future, the ginkgo tree will offer students the opportunity to reflect on their own lives while perhaps exploring these differing historical narratives, McGaughey says.

“The past isn’t necessarily a blueprint for how we should do things. I think we are free to decide for ourselves what should come next,” McGaughey says. “That’s what I hope that the tree can be — a place where people can reflect on, ‘So what is the right thing to do here?’”

For Wang, a Bates politics major and Japanese minor, the relationship between his home country of China and Japan is storied and complicated. Fighting between China and Japan during World War II exacerbated the two countries’ fraught political relationship and, for many, established an enduring resentment between the two populations, a feeling only complicated by the devastation Japan experienced during the atomic bombings.

With this historical context, some people, Wang says, may be surprised to see someone from China advocating so strongly for something like the preservation of the hibakujumoku seeds.

But, after studying Japanese for two years at Bates and studying abroad in Japan, Wang holds two things to be true at the same time: the relationship between his home country and Japan has been a difficult one, and the atomic bombings in Japan were unequivocally devastating.

“All of that has some nuanced influence on my opinion of the seed,” Wang says. “But at the end of the day, it came from something that survived the bomb. The wonders of life, the resilience of this being, I think, deserve celebration.”

Ginkgo trees can live for thousands of years. Bates’ tree may live on to see the next generation of people, and the next, and the next, its legacy of survival and hope enduring for centuries to come.

Faculty Featured

Keiko Konoeda

Lecturer in Japanese

Hanna S. McGaughey

Assistant Professor of Japanese Language and Asian Studies

Daniel Slane

Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology