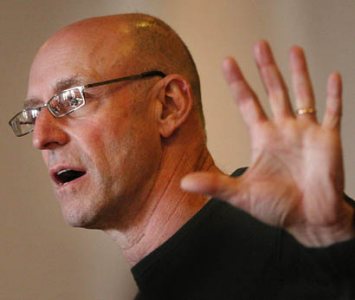

Food writer Pollan explores ‘American paradox’

“The science around food,” said Omnivore’s Dilemma author Michael Pollan to a rapt Bates College audience on Oct. 27, “is basically where surgery was in 1650.”

Then he asked, “Are you ready to get on the table?”

The line drew one of many big laughs from the capacity crowd at the college chapel. Yet therein, too, lay a key theme of Pollan’s talk: In what he calls the “American paradox,” the U.S. obsession with nutrition has actually given this nation “some of the lousiest nutritional health in the world.”

“The ideology that we bring to food and eating decisions really is the problem,” he said. He calls this ideology “nutritionism,” and says its disciples have put their faith in imperfect, even destructive, science and food-industry marketing.

The annual Otis Lecture at Bates, Pollan’s droll, fact-rich talk was titled In Defense of Food: The Omnivore’s Solution. (Because scores of would-be listeners were turned away from the crowded chapel for the evening talk, he reprised the address the following morning.)

His appearance was timely, coinciding with the College’s yearlong Bates Contemplates Food initiative, examining where food comes from and what it means. During Pollan’s two-day stay at Bates, an institution whose dining practices he praised as “light years ahead of many other places,” the award-winning writer and journalism professor visited around the campus community and offered an informal talk about writing on Monday afternoon.

Pollan summarized concepts from his best-selling Omnivore’s Dilemma (2006) and this year’s In Defense of Food. Ultimately, he asked his listeners to shun nutritionism and the Western diet of refined stodge and feedlot meat; seek out food from sources as natural as possible; and remember that “if everybody sought out real food, whole food, cooked it themselves, and ate it with friends and family, [so] much would change in this country.”

Nutritionism sees food as a “delivery system for nutrients” and eating as an activity relating solely to health. It borders on religion, complete with a priesthood — nutritional scientists, food-industry marketeers and their willing acolytes in the press — and a Manichean worldview of good vs. evil food components.

A highlight of the talk was a history of nutritionism, which Pollan linked to late-19th-century grainy gurus like John Henry Kellogg and Charles William Post. And resonating with listeners of a certain age, many of whom still wonder where “draft beer in a bottle” came from, was Pollan’s reminder that today’s nutritionism is rooted in the 1970s.

In 1973, under food industry pressure, Congress repealed a regulation that compelled manufacturers to label certain imitation foods as “imitation.” That opened the door to all sorts of substituted ingredients and such curious products as fat-free sour cream.

Four years later, Sen. George McGovern presented the Senate’s well-intended “Dietary Goals for the U.S.,” calling for fewer saturated fats, refined grains and sugars. McGovern’s report, Pollan explained, put the government for the first time in the role of trying to influence the eating habits of all Americans on the grounds of health.

But in a fascinating sort of ju-jitsu, the food industry took what was in fact a critique of its methods and parlayed it into a “brilliant new marketing strategy”: using the government guidelines, and later the auguries of nutritional science, to build a whole new profit center around nutritionally engineered products like Nabisco’s Snackwells line of diet confections.

The industry found some “magic words: If you put ‘low-fat’ on a food, people will eat a ton of it,” Pollan said, to laughter. “The obesity epidemic and the public health campaign to get fat out of the diet coincide.

“What a public health disaster.”

In short, Pollan said, the “science behind nutritionism has just been completely wrong.” Both the chemical composition of foods and the absorptive powers of the living body are too subtle and complex for current science: “You have a mystery on both ends of the food chain that has thwarted any attempts to really reduce it.”

Where science has gone astray, cultural tradition and family wisdom over the millennia successfully conveyed information people needed to survive on the foods naturally available to them — a surprisingly wide spectrum of foods. Traditional diets are incredibly diverse, Pollan said. “There is no ideal human diet. One of our great good fortunes is that we can do well on whatever nature has to offer on six of the seven continents.”

So “there is no one proper way to eat,” he said. But “there is one way not to eat” — the Western diet. “How could civilization, 10,000 years after the birth of agriculture, have come up with the one way that reliably makes people sick?”

Prior to the question-and-answer session that ended the evening, Pollan reminded listeners of the unbreakable relationship among healthy people, healthy communities and healthy agriculture. “It turns out that what is best for our health is best for the health of our agriculture too. It really is a win-win, because what our agriculture really needs is to diversify” away from its dependence on monoculture and chemical inputs — “and what we need to do as eaters is to diversify, to eat many different real foods.”

He also offered a few of his rules for eating, including the seven-word phrase that has become a mantra among Pollanites: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Suggesting that we avoid “any food that won’t eventually rot,” he described a package of Twinkies that has sat in his office apparently unchanged for two years. “The microbes . . . are not interested,” he said, to laughter. “The microbes leave them alone. And we should, too.”