Rice-DeFosse co-authors history of Twin Cities’ Franco-Americans

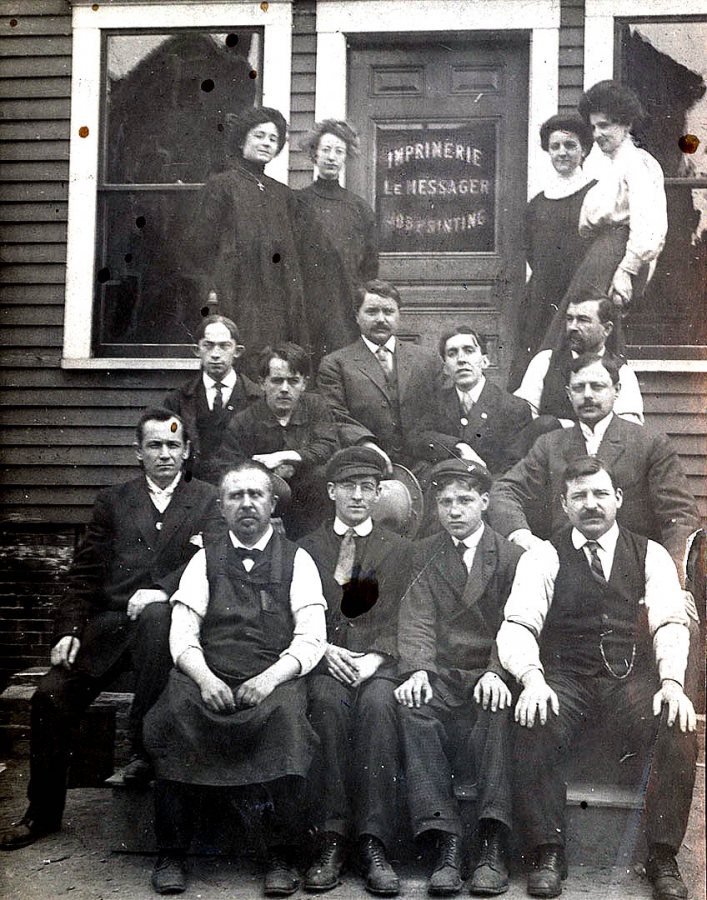

Staff of Lewiston’s French-language newspaper Le Messager, circa 1910. From “The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn,” courtesy of the University of Southern Maine, Franco-American Collection.

Even though Bates professor Mary Rice-DeFosse and James Myall have studied Lewiston-Auburn’s Franco-American community for years, it can still surprise them.

While researching their new book, The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn (The History Press), the first comprehensive history of this community written for a general audience, they encountered a few shocks.

“There were lots of little details that were hidden even to people who had looked at that history for quite a long time,” says Myall, former coordinator of the University of Southern Maine’s Franco-American Collection and now executive director of the Freeport Historical Society.

One of the biggest bombshells (“I have trouble just picking one,” he says) came from early 20th-century local newspaper accounts of Franco-American children playing in the city dump in Little Canada (Lewiston’s Franco-American neighborhood) — a structural reminder of the discrimination and oppression new immigrant groups often face.

The authors were not the only ones to be surprised by the stories the book uncovered. “Although Franco-Americans are proud of their history, they don’t know how much they have to be proud of,” says Rice-DeFosse, a professor of French and Francophone studies.

- On April 27, 2015, Rice-DeFosse will be one of three faculty from Maine colleges and universities to receive the Maine Campus Compact’s Donald Harward Faculty Award for Service-Learning Excellence. “Her community-engaged work hits the faculty trifecta,” says Bates Harward Center director Darby Ray, “as it involves substantial service to the off-campus community, innovative pedagogy and published scholarship.” In 2014, Rice-DeFosse was inducted into the Maine Franco-American Hall of Fame.

Myall and Rice-DeFosse saw a need for the book within the Franco-American community, to share with its members the details of their rich history, but they also wrote the book for a wider audience, to cast doubt on popularly held beliefs about immigrant identity and assimilation in America.

Sylvia and Rosaire Roy at WCOU Studios on Lisbon Street, Lewiston, circa 1945. From “The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn,” courtesy of the University of Southern Maine, Franco-American Collection.

“We have a notion of the American melting pot: immigrants come, the first generation doesn’t speak any English, the second generation learns English and the third generation is assimilated,” Rice-DeFosse says. “And Maine’s Franco-Americans do not follow that pattern.”

Instead, Rice-Defosse and Myall reveal in their book an extraordinarily resilient community of Americans who have managed to preserve their French and French-Canadian roots since they started to arrive in the Twin Cities in the mid-19th century to work in the Androscoggin River mills.

The chapters, organized chronologically, are divided into short sections that cover material spanning arts (early 20th-century Lewiston was once dubbed the “Athens of French America”), festivals (like the 1925 snowshoe convention/”beer fest” held openly during Prohibition) and religion — the Church of SS Peter and Paul, an iconic building of the Lewiston-Auburn skyline, was built by 1936 on the “nickels and dimes” of faithful Franco-American parishioners. (It was reclassified as a basilica in 2005.)

A child at an unknown textile mill in Lewiston, circa 1900. From “The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn,” courtesy of the University of Southern Maine, Franco-American Collection.

The book proceeds into the present, finishing with the reaction of the Franco-American community to the influx of African refugees (some of whom speak French) and the gubernatorial race between incumbent Paul LePage and U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud — two Franco-American candidates. “We really took it right up to the wire, considering we were writing about things that were happening the week before,” Myall says.

The co-authors, who had previously worked together on the board of the Franco-American Collection, enjoyed the collaboration. “We complemented each other nicely between a historical perspective — my primary interest — and Mary’s interest in the language and culture,” Myall says.

Myall and Rice-DeFosse brought to the book research that dovetailed to form a complete portrait of the Franco-American community.

Rice-DeFosse has worked with Bates students, particularly those in her course titled “French in Maine,” for years to collect the oral histories of local Franco-American residents. While the interviews started as a way for her students to practice their French language in the community, they evolved into an indispensable source of history.

“I have a record of a number of people’s lives, their life stories…that was the reason we were able to do the book,” Rice-DeFosse says.

Myall brought his knowledge of the huge amounts of information housed in the Franco-American Collection. The collection, the University of Southern Maine’s store of Franco-American archival material (and one of the largest in the state of Maine), contains a plethora of primary sources — old newspapers, diaries, recipe books and thousands of images. Most are donations.

“We really appreciate [that] the information we were getting came mostly from the community in one form or another,” Myall says.

That is what makes The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn not only a compelling read for American history buffs, but a source of empowerment for the community itself.

“A lot of people say, ‘Thank you for recognizing our history and writing down these things that we all knew, but nobody has written down before,'” says Myall of reactions to the book. “But then there’s also another group of people — or the same group of people — who sometimes say, ‘This is great; I never even knew this about my own heritage.'”

The potential audience for this book extends well beyond the Lewiston-Auburn city limits. Myall encourages anyone from Maine and New England, a region rich in Franco-American influence, to read about this important population.

Rice-DeFosse sees connections in this history for the study of all people who live in border communities, “who in fact are fully American, in every sense, but who also have retained culture and sometimes language over generations.”