West to east, from Keizer, Ore., to Manning, S.C., Bates alumni in the path of Monday’s total eclipse talk about their plans, what’s afoot in their towns, and what has surprised them about the run-up to the big day.

Noah Petro ’01 — Keizer, Ore. — 10:17:26 a.m. PDT

When the eclipse begins its totality in Keizer, Ore., NASA scientist and baseball fan Noah Petro ’01 will begin his moment in the sun.

A deputy project scientist for NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, Petro will represent NASA at a minor league baseball game that will have the first eclipse delay in professional baseball history.

Of the four minor-league games in the path of the total eclipse on Monday, the game between the Salem-Keizer Volcanoes and the Hillsboro Hops is first: Gametime is 9:35 a.m. PDT.

Petro, accompanied by his wife, Jennifer Giblin ’01, and two young children, will join a team of NASA scientists and outreach specialists at the game, and they’ll speak about the science behind the eclipse and how to safely view it.

A deputy project scientist for NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Noah Petro ’01 will represent NASA at a minor league baseball game in Oregon, the first to experience an eclipse delay. (Photograph by W. Hrybyk / NASA)

The game will stop after the first inning for the eclipse. The delay will last about 30 minutes to give everyone time to get ready for totality. The moments of darkest shadow will last about 2 minutes.

“Having never seen a total eclipse, I’ll just try to soak it all in,” says Petro, who lives in Alexandria Va., and works at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Still, he’ll been looking carefully. “I’ll keep my eye peeled for Venus which should be visible (as well as a few other planets), I’ll look for structure in the corona which is only visible during totality.”

Petro says that the eclipse delay will be the first in the history of professional baseball, and perhaps professional sports. (In February 1980, a cricket match in India was postponed a day to avoid playing during a partial eclipse.)

“Gene Clough would be proud,” Petro says, referencing beloved Bates physics and geology faculty member, now retired.

“People should take eye safety very seriously, regardless where they are,” he advises. “NASA has a series of safe viewing tips. Folks should take the opportunity to look at the eclipse (safely), no matter where they are.”

The NASA mission I work on, LRO, has “created the highest-resolution topographic map of any planet in the solar system,” he says. That means that NASA will be able to create “ the most accurate map of the shape of the eclipse — the shadow of the moon — ever.”

Chris Parrish ’93 and Deborah Kurnik ’93 — Corvallis, Ore. — 10:16:56 a.m. PDT

About 40 miles south of Petro’s baseball game, Chris Parrish ’93 and Deborah Kurnik ’93 are letting their 12-year-old daughter, Katherine, take the lead.

“She’s very excited about the eclipse,” Parrish says. Katherine has a treat planned: “Celebratory moon pies,” says Kurnik.

Forty miles south of Noah Petro ’01, in Corvalis, Ore., Christopher Parrish ’93 and Deborah Kurnick ’93 have moon pies ready for Monday.

“We’ll watch the eclipse from our own backyard,” says Parrish, an associate professor of geomatics in the College of Engineering at Oregon State University.

Like other colleges and universities in the path of totality, Oregon State is using the event to shine light on their contributions to science and education. Oregon State’s program is called the Space Grant Festival.

“We will be volunteering to help out at kids’ activity stations on both Saturday and Sunday,” says Kurnik, who is a grant writer in the College of Engineering.

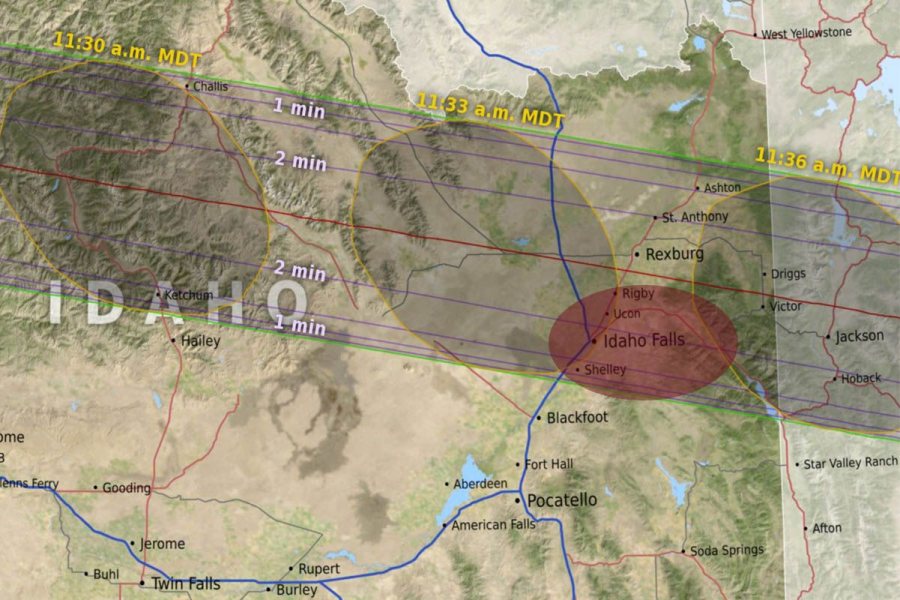

Barbara McIntosh ’59 — Idaho Falls, Idaho — 11:33:04 a.m. MDT

Eight hundred miles to the east in Idaho Falls, Idaho, retired special education teacher Barbara McIntosh is marveling at the crowds — 500,000 predicted to descend on her city, population 60,000.

“No rooms are available,” she says, “We are being told to have gas, food, and water on hand.”

“No rooms are available,” she says, “We are being told to have gas, food, and water on hand.”

Public officials are warning that the “usual four-hour drive from Salt Lake City to Idahol Falls could take eight hours.”

As for plans, she and her husband, Kenison, will watch from their back yard or a park across the street.

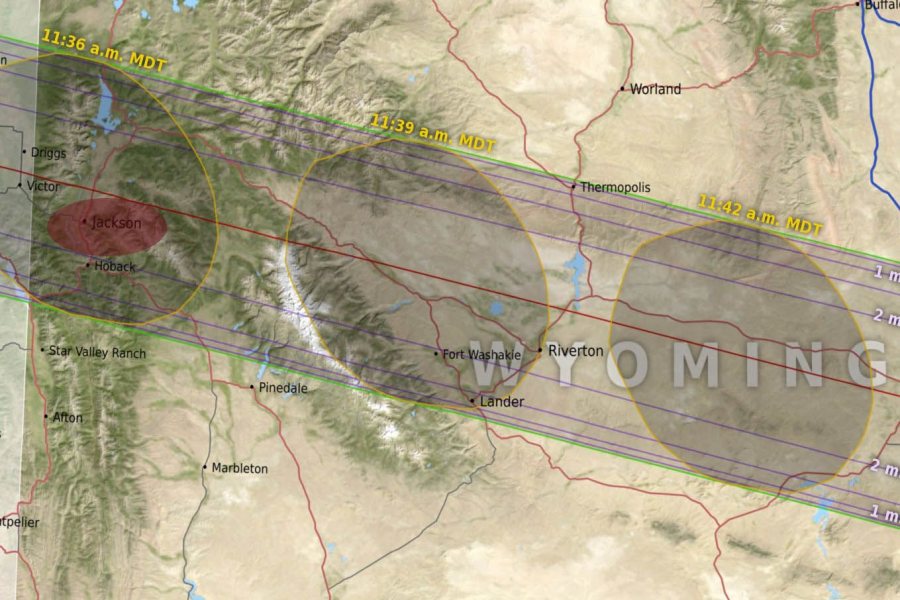

Carrie Noel Richer ’01 — Jackson, Wyo. — 11:34:56 a.m. MDT

Eighty-eight miles to the east in Jackson, Wyo., Carrie Noel Richer ’01 works at the Center for the Arts in Jackson, where she’s coordinating Observatories, a large-scale exhibition comprising 10 installations that use the eclipse “as a great lens to think about all that the eclipse brings to mind, while also commenting on the meaning and ideals of ‘the West.’”

As for Richer’s personal plans, her parents and a friends are in town for the event. “We are going to disappear into the Greys National Forest to a secret spot,” she says.

She’s eager to witness a distinctive eclipse phenomena. “Go to a tree and look in the shade of the tree’s shadow. You will see hundreds of crescent images of the partially covered sun all over the ground. Too cool!”

Featured in the exhibition Observatories, the sculpture “Hollow Earth” is made from glass and wood that creates the illusion of a tunnel descending deep into the Earth, housed in an abandoned shed. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for the Arts)

Jason Hall ’97 — St. Louis (just outside totality) — 1:18:00 CDT

Jason Hall ’97 has been a civic and business leader in St. Louis since 2005 when he teamed up with fellow lawyers to start Lawyers for Equality, the first gay lawyers’ association in the region.

Today, he’s co-founder and managing director of a start-up civic initiative, the Arch to Park Collaborative, in St. Louis.

“I feel pretty lucky that I’ll be walking outside of my office and taking the moment in so easily,” he says. “I am surprised at how Monday is turning into the equivalent of a national holiday around here!”

Just outside totality, he’ll be at casual watch party that’s being hosted “in our urban innovation district in St. Louis, the Cortex Innovation Community,” he says.

“So, I’ll be surrounded by many other entrepreneurs and innovators enjoying the historic moment.”

Sandra Shea ’75 — Carbondale, Ill. — 1:20:05 p.m. CDT

About 130 miles to the southeast of Jason Hall, Sandra Shea ’75 is near ground zero for the eclipse. There, the totality will be its longest: 2 minutes and 37 seconds.

In the southern part of Illinois, Carbondale, where Sandra Shea ’75 lives and works, is considered ground zero for the eclipse.

She works at Southern Illinois University. Along with around 15,000 others, she’ll be at SIU’s Saluki Stadium with NASA scientists and astronomers from Chicago’s Adler Planetarium.

“I’ll be with family and friends, including a friend from Bates, Jean Seitzer Storrs ’78, and her family.”

She’s completely captivated by the event. “I’m a nerd, I admit it,” she says. “Everything about the eclipse is interesting. I teach psychology and neuroscience at the School of Medicine, so science is everywhere, every day.

“I’ve seen partial eclipses but never a total. And we get to do it again in 2024 when another total eclipse will cross Southern Illinois in almost exactly the same place!”

Carbondale officials expect 70,000 visitors to the town, which has a population of 26,000; state officials predict up to 200,000 to the southern part of the state.

Special events are everywhere, Shea says: an Eclipse Comic Con at the university, craft fairs, and days of concerts in different towns. There’s Shadowfest in Carbondale and Moonstock in Carterville. At the latter, Ozzy Osbourne will be singing “Bark at the Moon” as the sky goes dark.”

Elizabeth Lemerise ’74 — Bowling Green, Ken. — 1:27:34 p.m. CDT

Two hundred miles to the east, in Bowling Green, Ken., Elizabeth Lemerise ’74 is making the most of her location.

The University Distinguished Professor of Psychological Sciences at Western Kentucky University, she’s going to watch from home, about 10 miles south of campus.

At home, “there’s a longer totality than on campus — 1 minutes, 20 seconds, instead of about 50 seconds.”

Not that she’ll skip the first day of classes at her university. The school has pushed back the start of classes until 4 p.m.

Like others, she’s amazed at the predicted throngs and is heeding the warnings from public-safety officials.

“Kentucky expects half a million people to come for the eclipse. Every hotel room in town is booked for the night before, at ridiculous prices, too. The locals have been advised to get their gas and groceries and to stay home!”

Marty Braman Duckenfield ’67 — 2:37:10 p.m. EDT — Clemson, S.C.

Uh-oh.

“To my horror,” reports Marty Braman Duckenfield, “I discovered that our big family gathering is this coming week on Cape Cod. With so many moving parts, plus a contract signed last summer, I will be in Barnstable, Mass.”

There, about 63 percent of the sun will get covered on Monday. “The skies look clear, it’s a perfect place for viewing, and I’ll be surrounded by those I love,” she says. Though it’s a “major blow,” to miss totality, “I’m trying to look at the bright side.”

Duckenfield is an associate producer for Clemson Broadcast Productions, which “has a full court press to record it all, in the skies and down here on Earth.”

Katherine Bernier ’11 — 2:38:03 p.m. EDT — Greenville, S.C.

Katherine Bernier ’11 has a plan to avoid the mobs of eclipsers. She and friends from Richmond, Va., have rented kayaks and will paddle far from the madding crowds on a local lake. “Greenville and Clemson University are supposed to be crazy!”

Bernier is starting her second year of a master’s program for environmental planning at Clemson.

What’s impressed Bernier is “lots of planning. I’m glad that schools are either starting late or allowing students to leave early.” She’s also noticing “a focus on education” about the eclipse. For example, the Greenville Zoo is supposed to be packed for observing the animal reactions.”

“I guess I can say I’m disappointed how ridiculous the pricing is for plane flights down here, due to the demand.”

Monthe Kofos ’11 — Manning, S.C. — 2:44:02 p.m. EDT

For Monthe Kofos, it’s location, location, location.

He lives a few miles south of Manning, S.C., on Lake Marion. “The exact center of the path passes straight over my house,” he says.

He thought of traveling to Charleston to watch the eclipse on the beach. “With all the expected chaos and traffic, I’m concerned about the return trip, normally about an hour.”

In his final year of medical school, Kofos is also an avid photographer. Like millions of others, he’s hoping to take some “some cool pictures of the eclipse over the water — provided it is sunny.”

Like other alumni coast to coast, Kofos is stunned by the buzz. “Never did I guess there would be so much hype surrounding this event,” he says. “It also surprises me how many ‘fake eclipse glasses’ are being sold.”

Still, “the benefit is that it provided a cool opportunity to learn more about a solar eclipse.”