King would be ‘appalled’ at today’s rhetoric around poverty, Butler says in keynote

Millions of Americans have slipped and slid into poverty in recent years because of their own financial ignorance, the erosion of mutual helpfulness in society and predatory megachurches that espouse prosperity theology at parishioners’ expense.

But getting the estimated 46 million poor Americans out of poverty will require wholesale changes in how we talk about, think about and take action around poverty.

So said author, religious studies scholar and media commentator Anthea Butler, keynote speaker for the college’s 2013 Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance on Jan. 21.

Anthea Butler, associate professor and graduate chair of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, delivers her keynote address, “MLK and America’s Bad Check: America’s Poor in the 21st Century” in the Gomes Chapel. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

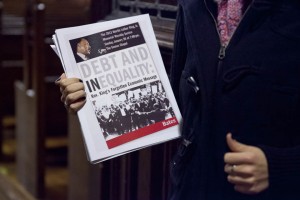

Delivered from the Gomes Chapel pulpit, Butler’s address, “MLK and America’s Bad Check: America’s Poor in the 21st Century,” was a pointed reflection on the overall theme for the college’s observance, Debt and Inequality: The Relevance of King’s Forgotten Economic Message.

Her prescriptive message on Monday morning represented something of an answer to the homily she offered the night before at the MLK Memorial Service.

The homily, based on the book of Isaiah and the theme of captivity, was referenced by Charles Nero, professor of rhetoric and faculty member of the African American Studies and American Cultural Studies programs, as he introduced Butler on Monday in his role as chair of the MLK Planning Committee. Nero said:

Dr. Butler argued convincingly that we as a nation are in captivity. We are in captivity to guns, to debt, to fear, to poverty. How do we make our way out of this captivity, Dr. Butler asked. This is the question, she says, we must ask ourselves.

The day’s theme reflects Martin Luther King Jr. focus on poverty beginning in 1967, a “forgotten economic message” today. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

In her keynote, Butler began her to question her question by looking back at the Poor People’s Campaign, a six-week program of nonviolent action in Washington, D.C., in the late spring of 1968.

“I’m a historian,” explained Butler, an associate professor and graduate chair of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania. “Looking back is an important way to look forward.”

The Poor People’s Campaign, King’s brainchild and undertaken after his April 1968 assassination, marked a turning point of the civil rights movement. Despite the Great Society programs and gains of the civil rights movement, “Negros are still impoverished aliens in an affluent society,” King said.

In other words, said Butler, it didn’t mean much to be able to sit at the lunch counter “if you couldn’t afford the hamburger being sold at the lunch counter.”

The Poor People’s Campaign featured an encampment on the Washington Mall. It became a place where activists collaborated around a loose set of goals; where protesters lived in tents and lean-tos; and where a system of food distribution kept everyone fed.

Protesters march at Lafayette Park and Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C., on June 18, 1968, during the Poor People’s Campaign. Photo: Warren Leffler, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Butler compared it to the Occupy movement, where people “came together to start to think about what can you do about poverty and impoverishment in this nation.” In a society of dizzying distraction, the Occupy movement was a rarity:

It was a moment in America where we focused our attention on people who were willing to camp out and say the economic system was wrong. How do we get that again? How do we start to talk about inequities without movements like Occupy? How do you do that?

One step, said Butler, is to change the way we talk and think about poverty in America. If King were alive today, she said, he’d be appalled that 15 percent of Americans live in poverty. But he’d be more appalled at the poor-are-lazy meme in society and the fact that “helping people has become a bad word,” she said:

I call this the nation’s new Ayn Rand philosophy: We’re all on our own; we can choose to be selfish; we don’t have to help anyone; and those we see who are impoverished are there because they want to be.

Butler launched her fiercest criticism at the “prosperity gospel.” Mostly identified with televangelists and Sun Belt megachurches, this theology suggests that good things come to those who don’t wait. “All you have to is quote enough Scripture, pay your tithes, pay your offerings,” and you’ll become prosperous, Butler says. “It tells you that can have your best life now.”

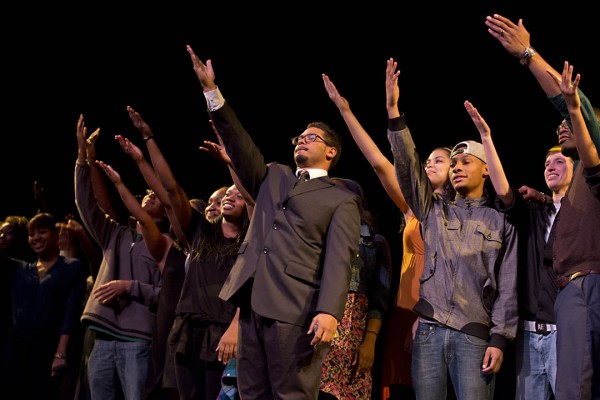

Robert Strong, graduate fellowship adviser and faculty member in English, and others respond to keynote speaker Anthea Butler’s call for a show of hands of student-loan holders. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

But that’s hardly true, Butler says. Whereas the African American church traditionally included sound financial advice as part of its ministry, the rise of the prosperity gospel has destroyed that tradition — to the great detriment of church parishioners.

It’s no surprise that Atlanta has had one of the country’s highest foreclosure rates, Butler said, because the metro area is home to prosperity gospel churches, like the Creflo Dollar Ministries and Bishop Eddie Long Ministries, that preach financial irresponsibility. The region’s failed mortgages “were bought by people paying attention to the prosperity gospel.”

The prosperity gospel is emblematic of a moral change in Christian society, she said:

The moral center has changed in the community; the moral center has been to give to your church and help each other, now the church has become a capitalist place to make more money. This is wrong.

It’s a problem bigger than religion, she said. “All of us have a part of this. We’re not training people about money. We have a country of people who don’t know the value of money. We spend and we spend and we spend.”

Solving the poverty problem needs to move beyond the more government / less government argument, Butler said. It even needs to move beyond discussion and posturing.

“I’m tired of the bus tours,” she said, perhaps a reference to the high-profile “Poverty Tour” by Tavis Smiley and Cornel West in 2011. “I don’t know what it gets you if you ride a bus, but you haven’t done anything about feeding someone at the local homeless shelter,” she said.

After the morning keynote, a variety of afternoon panel discussions featured community leaders, students and faculty. Featuring recent Bates sociology research, this panel discussed ways to build financial literary among Lewiston-Auburn’s immigrant community. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

Instead of observing, we must “realize that we have poor people who will be intrinsically harmed, and their children will be intrinsically harmed” if we do not take action to help.

Helping, she said, means “changing the rhetoric about poverty and inequality.”

Helping, she said, means “working on poverty in your community. Push back against the language that says you can’t help someone. You might even consider put yourself on the line, in a religious or nonreligious environment, working with those who are homeless.”

She closed with a story about a homeless man in her neighborhood who had resigned himself to his homeless fate. “I’m old,” he told Butler during one of their conversations. “But I wonder how it’s going to be for all the rest of you?”

Earlier in the morning, as the keynote audience arrived at Gomes Chapel, they were warmed up by Three Point Jazz Trio (physicist John Smedley on guitar, music professor Dale Chapman on alto sax, and community member Tim Clough on bass) and their final number, Thelonious Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser.”

After all that jazz, Associate Dean of Students James Reese, considered a founder of the King Day observance at Bates offered a few remarks that drew gasps and applause from the gathering: see story.

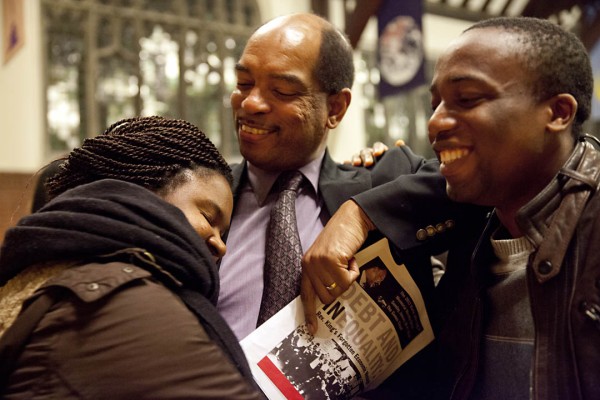

Associate Dean of Students James Reese greets Linda Kugblenu ’13 and Victor Babatunde ’11 after the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Service on Jan. 20 in the Gomes Chapel. Photograph by Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College.

Following Reese, President Clayton Spencer invoked the day’s “spirit of self-challenge rather than self-congratulation” by emphasizing that economic inequality should not been seen as inevitable result of “globalization, technology, and cheap manufacturing costs elsewhere in the world.”

Rather, she said, quoting Nelson Mandela, “like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is man-made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.”

Spencer said that colleges like Bates “have a choice to make” about their role in solving poverty, about “whether we will succumb to the forces of inequality or throw our institutional weight, however small it may be, into counteracting these forces”:

We make the choice a matter of shared values when we encounter each and every member of this community as an individual deserving of dignity, respect and the opportunity for self-realization.

Following Spencer, Dean of the Faculty Pam Baker ’69’s overview noted that “hand in hand” with the opportunity for study and reflection in a college setting is the responsibility to take “informed and ethical action.”

In that vein, King Day programming “challenges us to think critically about privilege and responsibility, poverty and opportunity, justice and equality.”