A professional athlete negotiates a contract extension. A hiker negotiates difficult terrain.

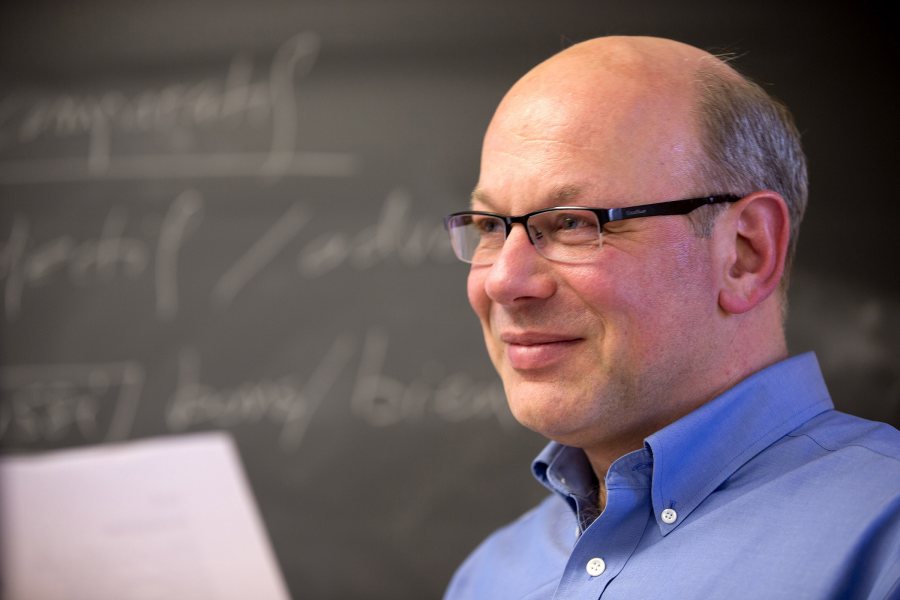

Professor of French and Francophone Studies Alexandre Dauge-Roth is known internationally for his research into the narratives of survivors of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. When he uses the word “negotiate,” he means this:

“For the survivor of genocide or another traumatic experience, the meaning and memory of that experience has an ongoing resonance, or rather a haunting dissonance, that requires constant negotiation, which is triggered by the cultural and political demands that define the present from which the traumatic past is re-envisioned.”

For more than a decade, Dauge-Roth and his students have traveled to Rwanda to interview survivors and hear their stories. This indirect act of “bearing witness,” he explains, is nevertheless a “mutually transformative encounter for both survivor and interlocutor” — one that demands an approach to testimony as a “social and cultural practice of negotiation.”

Alexandre Dauge-Roth, associate professor of French and francophone studies, shown during a class. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

On the one hand, he continues, “survivors negotiate the possibility of having their trauma socially recognized and their present-day demands heard.”

The concept of negotiation “highlights the fact that cultural and existential trauma requires an ongoing and demanding effort.”

On the other, “we — the listening community — must negotiate the historical place, cultural resonance, and political meaning we are willing to give to a highly disturbing experience that embodies the transgression of all ethical norms and the collapse of the social bond.”

In the end, the concept of negotiation “highlights the fact that bearing witness to cultural and existential trauma requires an interruption, a demanding effort to listen, and an ongoing creativity. The meanings of experiences of pain and suffering are confined neither to a past experience nor to survivors alone.”

All testimonial encounters between survivors and their interlocutors engage “multiple views, expectations, trajectories, histories, dynamics of inclusion and exclusion, and all the relationships of power and knowledge that the cultural negotiation of a traumatic past entails within a mutually shared present.”

Academic disciplines often assign particular and surprising meanings to common words. The series “What I Mean When I Say” explores those meanings.