Forty-five years ago this fall, the Clean Water Act became law thanks to the work of U.S. Sen. Ed Muskie ’36 of Maine. That we know.

Less well-known is that President Nixon initially vetoed the act, calling the legislation “extreme and needless overspending.” (The veto is so little known that some websites credit Nixon with signing the bill.)

In the Senate, Muskie led the rapid and successful override effort, and the bill became a law on Oct. 18, 1972. Muskie ridiculed Nixon’s opposition, using speech-making tactics likely learned as a Bates debater, including these pointed rhetorical questions, each starting with “Can we…?,” a technique known as anaphora:

“Can we afford clean water? Can we afford rivers and lakes and streams and oceans which continue to make possible life on this planet? Can we afford life itself”?

Today, environmental economists like Lynne Lewis, the Elmer Campbell Professor of Economics at Bates, are adding oomph to Muskie’s blistering rebuttal by measuring the financial benefits of clean water, at a time of ongoing federal efforts to water down the law.

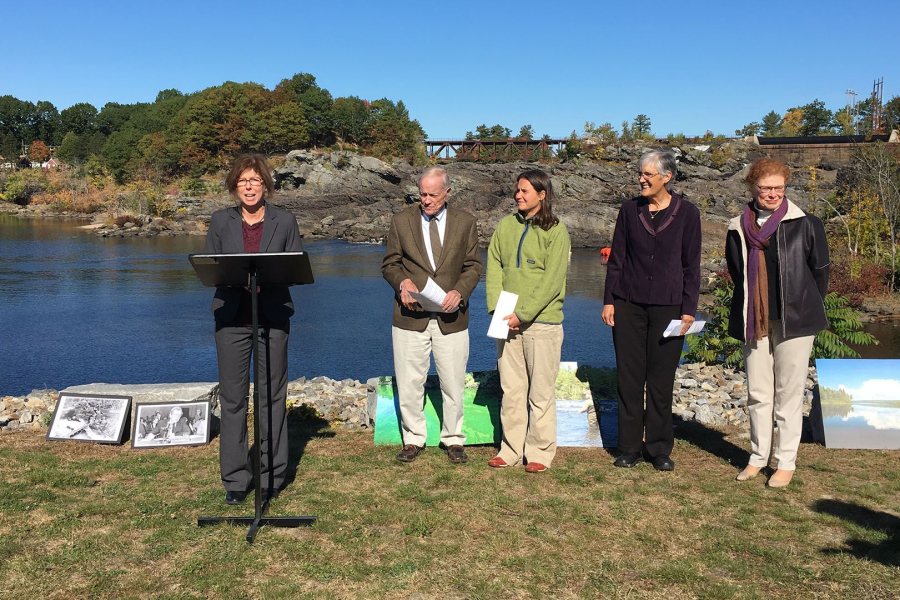

Bates environmental economist Lynne Lewis (left) speaks during a media event at Veterans Memorial Park along the Androscoggin River in Lewiston on Oct. 18. Also speaking were, from left, Dick Anderson, former Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife biologist; Natalie Lounsbury of River Rise Farm in Turner; Lisa Pohlmann, executive director of the Natural Resources Council of Maine; and Beckie Conrad ’82, president and CEO of the Lewiston Auburn Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce. (Courtesy of Lynne Lewis)

Last month, on the 45th anniversary of Muskie’s landmark Clean Water Act, Lewis offered some of that evidence as she spoke at a press event sponsored by the Natural Resources Council of Maine and held along the Androscoggin River:

Good morning. I am an environmental economist. Many people I meet ask what that is. Environmental economics is, in part, focused on measuring the costs and benefits of environmental policies. The Clean Water Act, authored by Sen. Edmund Muskie, a graduate of Bates College here in Lewiston, has been enormously successful in economics terms — meaning providing economic benefits well in excess of the costs of compliance.

The Clean Water Act provides billions of dollars in economic benefits annually, by protecting the water we drink and in which we fish, swim, boat in, and live near.

For a state like Maine that is literally filled with rivers, lakes, streams, and coastline, clean water provides enormous economic value to our state in the form of reduced health care costs, improved recreational opportunities and tax revenues to the state from increased tourism. From my research and that of others, it is clear that clean water significantly increases waterfront property values for both homeowners and businesses.

Thriving businesses and community events take place along rivers such as this. These revenue sources did not exist before the Clean Water Act. The Clean Water Act has resulted in a rebounding of river herring and other sea-run fish, contributing to the health of our Gulf of Maine fisheries.

The crowd-pleasing success of the Great Falls Balloon Festival underscores the value of a cleaned-up Androscoggin River. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

According to a study by the University of Maine, our lakes contribute an estimated $3.5 billion to Maine’s economy annually, supporting 52,000 jobs. Clean coastal waters support the thousands of lobstering and fishing jobs that deliver landings of more than $700 million annually.

As a result of the clean water quality in Maine, the Portland Water District is one of only 50 water districts in the U.S., out of 50,000, that can forgo having a filtration plant. It would cost $70 million to build a filtration plant and an additional $1 million a year to maintain and operate that plant.

The Clean Water Act has done more to clean up our lakes, streams and rivers than any other single piece of environmental regulation.

Scott Pruitt’s efforts to cut EPA funding for programs that keep Maine’s waters clean, and undo a major water protection rule are examples of his moves to quickly and stealthily dismantle environmental regulations at the expense of those of us who benefit from them.

The Clean Water Rule, enacted by the Obama administration, was designed to take the existing federal protections on large water bodies and expand them to include the wetlands and small tributaries that flow into these larger waters. This rule closed loopholes that had left more than 55 percent of Maine’s stream miles and thousands of acres of wetlands at risk for pollution, thus threatening the drinking water of Mainers across the state.

Back in 2015, the EPA and the U.S. Department of the Army issued a report examining the costs and benefits of expanding the protected waters of the U.S. The original estimate concluded that the water protections would indeed come at an economic cost — between $236 million and $465 million annually.

But it also concluded, in an 87-page analysis, that the economic benefits of preventing water pollution would be much greater: between $555 million and $572 million.

It’s no surprise that the benefits of protecting America’s rivers, lakes, and streams far outweigh the costs. Whether we’re fishing or swimming or just drinking the water that comes from our taps, protecting our streams and wetlands is a win for all Mainers.

The need for clean water is not controversial. Our own Sen. Muskie, the driving force behind the Clean Water Act, knew this. We can’t afford to go backward on clean water protections. The Clean Water Act benefits all of us.

Held at Veterans Memorial Park on the Androscoggin — Exhibit A when it comes to the beneficial effects of Muskie’s landmark legislation — the gathering’s speakers also included Rebecca Conrad ’82, CEO and president of the Lewiston Auburn Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce. No stranger to the area — she co-owned an Auburn business for 20 years and has worked at Bates — Conrad said she knows “firsthand the river’s power and potential as an economic driver in the community.”