In August 1926, John Preston Davis sent a letter to Louis Costello, a Bates alumnus and former debater who was now a college trustee and Lewiston newspaper executive.

Davis himself had graduated that spring, leaving an impressive legacy as a debater. President of the Debating Council and editor of The Bates Student, he competed internationally and was part of a team that defeated debaters from Oxford. After graduation, Davis moved to New York City, to put his written and oratorical talents to practice in the flourishing Harlem Renaissance.

“Delta Sigma Rho should not be allowed to continue as a Bates organization.”

In New York, Davis decided to escalate his efforts to correct an injustice that he felt the college had not done enough to address. At the time, the highest honor a Bates debater could achieve was induction into Delta Sigma Rho, the national debating honor society. Davis met every requirement except one: The society did not admit black members.

In 1926, recent graduate John P. Davis protested Bates‘ membership in Delta Sigma Rho, a debating honor society that at the time excluded black debaters. Here, he is pictured, second from left, with H.H. Walker ’26, debate coach A. Craig Baird, Erwin Canham ’25, and Fred Googins ’27. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections)

In his letter to Costello — himself a Delta Sigma Rho member of the Class of 1898 — Davis said that “either Negro students should be frankly told before being mis-led into coming to Bates that privileges which are open to other students are in their case to be abridged; or else, Delta Sigma Rho should not be allowed to continue as a Bates organization.”

Davis’ letter was the latest to point out this stark conflict between Bates’ ideals and the reality in which it operated. Correspondence, articles, and meeting minutes in Bates’ Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library tell the story of the fraught and frustrating effort the college and its debaters made to get Delta Sigma Rho to admit black members.

Ultimately, it took two decades and a change in the national organization’s leadership before the society reversed its exclusion of black debaters.

Founded in 1906, Delta Sigma Rho’s central goal was to promote excellence in debating and raise the prestige of its members. The Bates Student trumpeted the creation of a chapter at Bates in 1915, even as it assured its readers that despite the Greek letters, it wasn’t that kind of fraternity.

“This is an honor reserved for colleges that have made their mark in intercollegiate debating contests, and is an honor that all Bates people will prize,” said the Student.

When Bates joined, Delta Sigma Rho did not have a formal rule excluding black debaters. But when Bates advanced the nomination of one of its star debaters, Arthur Dyer, who was black, the team quickly found out that the national organization enforced an unwritten policy of segregation.

“This provision must be adhered to by all chapters,” wrote national secretary-treasurer Stanley B. Houck in 1916 to Harry Rowe, Bates Class of 1912.

Rowe, the chapter’s secretary, was just beginning his long tenure as a Bates administrator, and Houck, his correspondent, would be a fixture in the national organization for decades to come. To prevent integration Houck would, at least on paper, appeal to the cohesion of the organization.

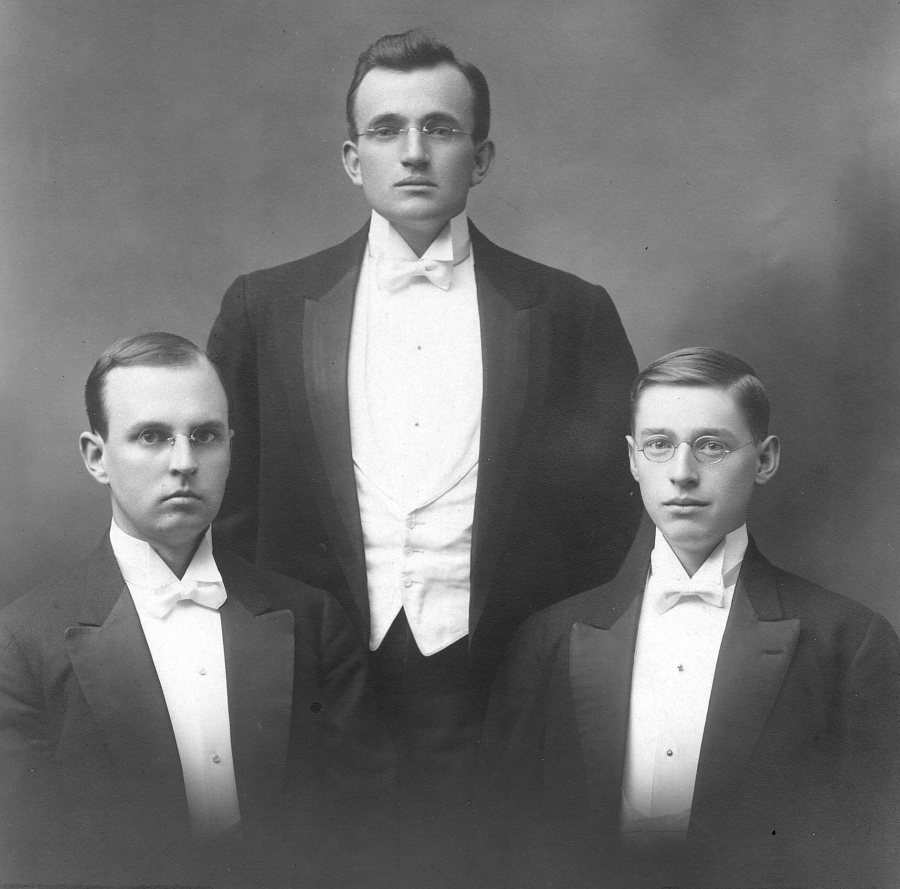

Arthur Dyer (left), Class of 1917, was the initial African American debater from Bates to be excluded from Delta Sigma Rho. He poses with fellow 1916–17 debaters Mervin Ames, Charles Mayoh, and Brooks Quimby. As Bates’ director of debate, Quimby would later take up the fight to integrate Delta Sigma Rho. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“The possible injury done to a few negroes by excluding them from membership would be offset by the good which the society could do in the South,” he wrote. “The welfare of the society required that there be no split between the Northern and Southern chapters on this issue.”

The Bates debate council went ahead with solidifying its Delta Sigma Rho chapter and inducting members, but at its first annual meeting in 1916, Rowe was told to write again to Houck “concerning Bates’ feeling in the matter of exclusion of negroes from membership,” according to the meeting minutes.

Rowe also sought other colleges’ support for a petition ahead of a National Council meeting in 1917, asking the University of Chicago for “your moral and active support in presenting a re-opening and re-consideration of the matter.”

“It seems to me,” Rowe wrote, “that if Phi Beta Kappa, an old and long established honor society makes no reservation as to race, color, creed, or sex, that Delta Sigma Rho might well follow this good example.”

Other Northern colleges seemed to be on the same page — Williams College asked Bates to support its own measure at the national meeting. Their efforts failed. “I personally appeared before the National Council at New Haven and remonstrated on their ruling, and was told that Chapters were not admitting colored men,” Rowe wrote in 1920 to Arthur Dyer, who had graduated three years earlier.

In 1920, Rowe wrote to the national conference, again asking it to change the rule. That year, Benjamin E. Mays, the future civil rights leader who served as president of the Debating Council and would have been eligible for Delta Sigma Rho membership, had graduated.

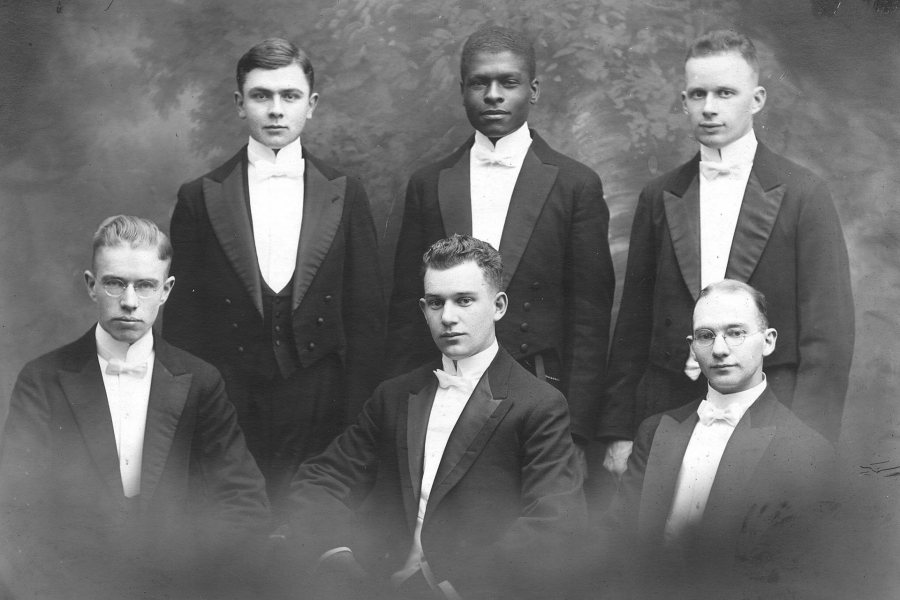

As a longtime Bates administrator, 1912 graduate Harry Rowe (left), a Delta Sigma Rho member, was the Bates point person in efforts to change the honor society’s racist membership rules. He’s shown in 1912 with fellow debaters Wade Grindle and Gordon Cave. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Not only were those efforts unsuccessful, but the society doubled down, officially changing its constitution to prohibit black members. Delta Sigma Rho held another national council in 1922, but since it was in Iowa, Bates could not send a representative. The chapter did, however, submit a petition to strike the phrase “not a negro” from the national constitution’s list of membership requirements.

The petition was less about taking a moral stand against racism and more about appeasing the chapters that did want to exclude black members; it emphasized that local chapters should have as much autonomy as possible. “The policy of local autonomy is very definitely limited by inability to elect negroes to membership,” the petition said. That petition, too, failed.

Meanwhile, Bates enjoyed the prestige and the networking opportunities that the society afforded its white members. Bates’ debating victories and its methods were covered extensively in Delta Sigma Rho’s publication, and debate faculty contributed articles. Around Commencement each year, The Bates Student published the names of new inductees, along with those inducted into Phi Beta Kappa.

In 1926, John P. Davis became eligible for membership in every way except his race. Meeting minutes in June of that year record that Marion J. Crosby, the chapter secretary-treasurer, was instructed to write to the national secretary, asking permission to induct Davis.

Houck, now the president of Delta Sigma Rho, replied with a firm, racist no. “Several negroes had been elected to membership with exactly the same result in each case, namely, the wrecking of the chapter and its practical non-existence as a functioning organization until the negro passed out of college and the memory of the members of the chapter,” he wrote.

(The society did not, as it happened, have a problem with women and with members of other minority groups becoming members).

“The Bates College chapter of Delta Sigma Rho can officially bestow upon and accord Mr. John Davis any distinct and special recognition for his ability as a debater which it considers desirable or appropriate,” Houck wrote, “so long as the recognition does not take the form of membership.”

Three weeks later, Davis wrote his letter to Costello, prompting Rowe, debate coach and professor J. Murray Carroll, and Bates professor and Delta Sigma Rho member Oliver F. Cutts to submit a statement to the college trustees.

“Some feel that Bates should no longer retain her charter,” they wrote.

“Others believe that altho the attitude of the national organization is regrettable, it is not the fault of Bates, but rather a part of the general disability under which negroes labor, and if Bates takes this course it will only deny her students the advantages of affiliation with this honor society without in any degree furthering the rights of the negro.”

The question of racism “stirred us up a bit,” wrote Brooks Quimby, the 1918 graduate who would later become a college legend as director of debate.

In 1920, Benjamin Mays (standing at center, with members of the 1919 Bates debate team) became the second Bates debater to be excluded from Delta Sigma Rho. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Getting the segregation rule changed, however, only became more difficult. During the 1920s, Delta Sigma Rho changed two key procedural rules: Not only did meetings now take place every five years, but any constitutional changes required the approval of four-fifths of the local chapters.

So the Bates chapter began, again, to gather support for a rule change ahead of the 1931 national council. Case Western Reserve University mounted its own campaign on behalf of one of its debaters, and the Wisconsin Legislature even passed a resolution urging Delta Sigma Rho to integrate so that a star University of Wisconsin debater could join.

“I see no credit in such logicians in a society like ours.”

Before the conference, Quimby wrote to Houck to let him know that Bates’ delegate would again try to get the chapters to vote to change the rule. Houck replied that he himself would put the matter to a vote — but he didn’t do so.

“Our delegate felt that both Houck and [vice president Gilbert] Hall did all they could to prevent the vote,” Quimby later wrote. “Mrs. Hall made the most remarkable argument to our delegate; that the reason that negroes wanted to get into D.S.R. was so that they could marry white women!”

Bates had not asked for full integration of Delta Sigma Rho, but that each chapter be allowed to make its own decision. “We shall be sorry if this causes any chapters to leave,” Quimby continued, “but, personally, I see no credit in such logicians in a society like ours.”

In the end, the 1931 national council did vote on whether to admit black members, and a strong majority voted yes — but not the four-fifths required for the measure to pass.

Delta Sigma Rho therefore remained segregated, but the damage to its leadership was done. Houck was re-elected president but, sensing a loss of support, resigned a couple months later. The new president was H.L. Ewbank of the University of Wisconsin, with Quimby joining the national leadership as vice president.

The groundswell of support for integration and the leadership shakeup did not translate into a sense of urgency — or perhaps procedural rules prohibited swift action. It was another four years before the prohibition against black members was finally lifted. Dyer, Mays, and Davis became eligible for Delta Sigma Rho membership.

By then, Davis had earned a law degree and was deep into a fight to ensure that African Americans were included in New Deal programs. In 1935, he helped found the National Negro Congress, an important civil rights organization, and became its executive director.

It seems Davis did not join Delta Sigma Rho. Over the next several decades, the organization would merge with a rival debating society. Bates is no longer a member.

Likely taken in Washington, D.C., in April 1940, this photo shows Bates alumnus John P. Davis (left), then executive secretary of the National Negro Congress, with Max Yergan (center) and U. Simpson Tate, congress president and treasurer, respectively. (Photo by Scurlock Studios/ Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History Archives Center)

Mays sent Brooks Quimby $17 for his membership dues. Soon to become the president of Morehouse College and earn the title “schoolmaster of the Civil Rights Movement,” he would be featured prominently as a distinguished Delta Sigma Rho member.

“It was my impression when I was in college that Bates had tried to make it possible for Negroes to become members of the National Forensic society of Delta Sigma Rho,” Mays wrote. “It is gratifying to know that Bates has kept on the job, and that after many years of effort she has won.”

Sources

For his senior honors thesis, Tom Connolly ’79 chronicled the history of Bates debate, including an entire chapter on the Delta Sigma Rho controversy. The thesis includes materials and personal conversations that are not available elsewhere, and is an invaluable source for future histories. It is available in the Bates archives.

The late Professor of Rhetoric and Director of Debate Robert Branham contributed a chapter about Benjamin Mays’ experience with debate, including the Delta Sigma Rho controversy, to Walking Integrity, a Mays biography. Branham, who died in 1999, also produced several documentaries, including one on John Davis (Lift Every Voice: John Preston Davis and the National Negro Congress).

The Delta Sigma Rho issue is also addressed in the college history Bates Through the Years, by the late Charles Clark ’51.