The universe has hundreds of billions of galaxies, many of which spit out gas and dust in a phenomenon called galactic outflow. It’s a high-speed process: In the most extreme cases, outflows can top 1,000 kilometers a second.

In a rare collaborative senior thesis project, Cristopher Thompson of Macon, Ga., and Kingdell Valdez of North Andover, Mass., are using data from the Hubble Space Telescope to, as Valdez says, “find out the characteristics and properties of our galaxies that are responsible for these extremely fast outflows.”

In doing so, they’re helping to wrap up a multi-year, NASA-funded effort to understand how gas leaves galaxies, which in turn can tell us about the nature of the stars and black holes in the galaxies.

Thompson and Valdez’s adviser, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy Aleksandar Diamond-Stanic, runs the Bates Galaxies Lab, which looks at how gas enters and leaves galaxies and the role of gas in the formation of stars.

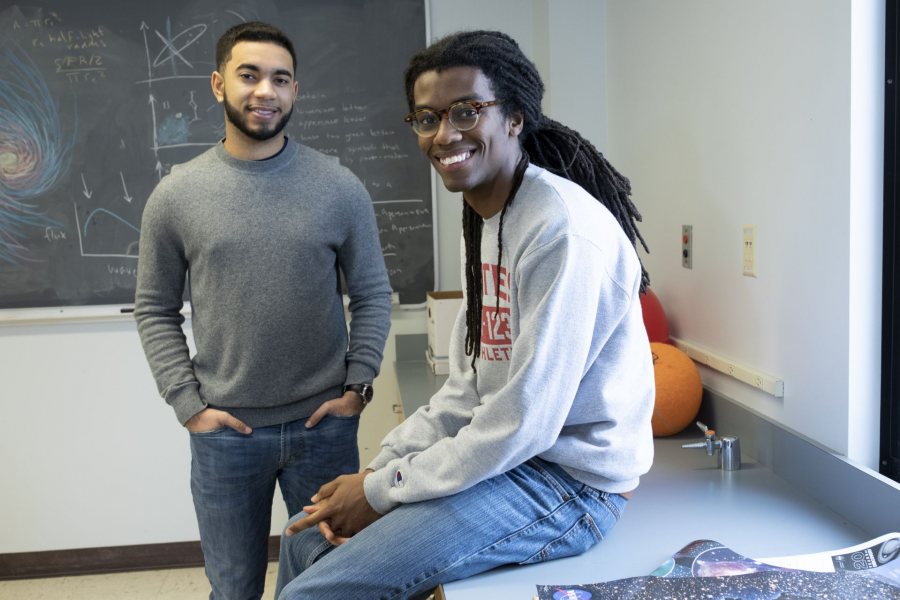

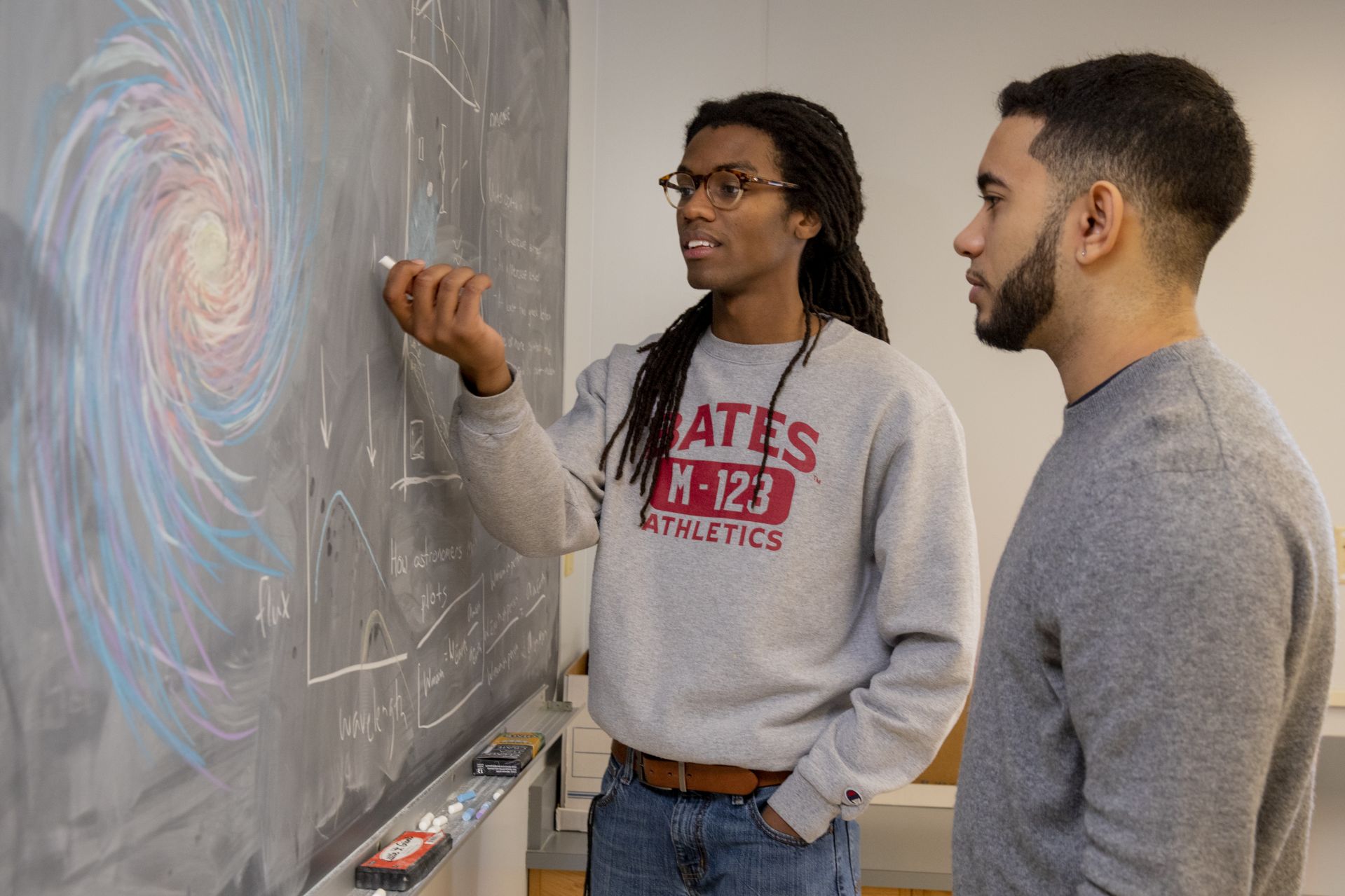

Kingdell S. Valdez ‘19 and Cristopher Thompson ’19, pictured in a physics lab in Carnegie Science Hall, analyzed 12 distant galaxies using data from the Hubble Space Telescope. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

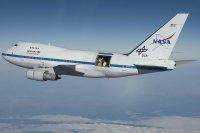

The Galaxies Lab has two overarching projects: contributing to the MaNGA project, which maps nearby galaxies using the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico; and looking at galaxies with the most extreme characteristics, using Hubble data. Other telescopes come into play as well: In 2018, Diamond-Stanic’s lab used NASA’s high-flying SOFIA telescope to zoom in on a single galaxy.

As in most Bates science labs, students are integral to the research, in this case analyzing the data that comes in from the telescopes. Credit for their senior thesis might just be for one semester, but the work that goes into the final document might span years.

“To see a project from beginning to end takes more than a semester, takes more than an academic year,” Diamond-Stanic says. “Being able to combine work over the summer with work done for thesis gets you closer to being done.”

Thompson and Valdez have both worked as summer research assistants in the Galaxies Lab and continued to work in the lab over the course of a few semesters. Once it came time to do their thesis, they both pivoted to galaxies with extreme outflows as captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Their work is supported by a grant from the Space Telescope Science Institute, a NASA organization that operates Hubble. Diamond-Stanic is the principal investigator on the grant, which includes several institutions across the U.S. and U.K.

Several students over the past two years have worked with data from optical light profiles of the 12 extreme galaxies — pictures of the wavelengths of light that are visible to us. In addition to optical wavelengths, Thompson and Valdez are now looking into images depicting wavelengths that are too short or too long for the human eye to see.

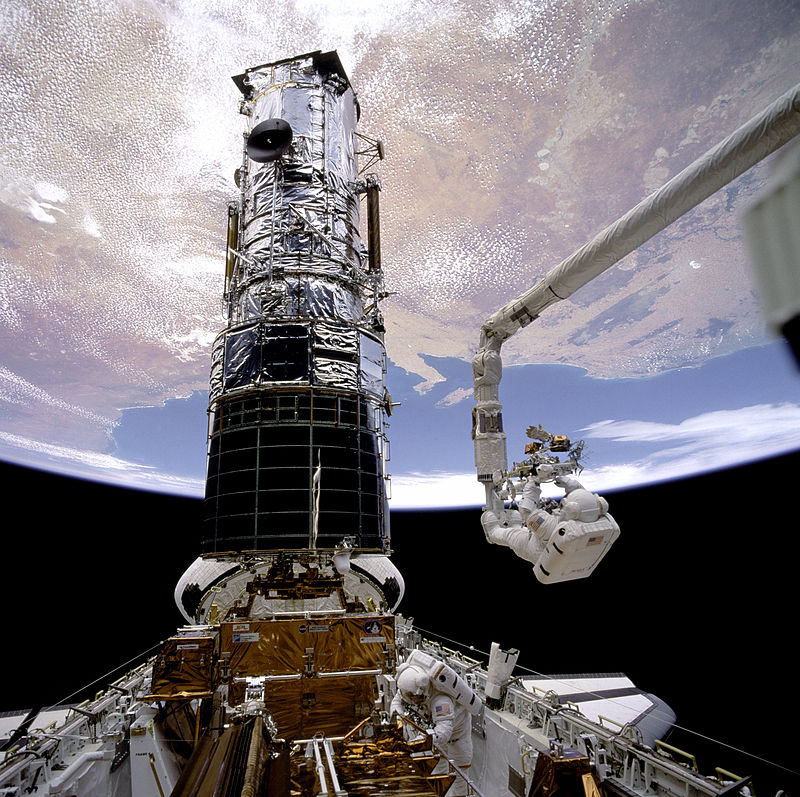

Astronauts F. Story Musgrave and Jeffrey A. Hoffman repair parts of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1993. The telescope provided data for a three-year project, headed by Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy Aleksandar Diamond-Stanic, on galaxies with extreme behaviors. (Wikimedia Commons)

Thompson and Valdez will turn in separate thesis documents at the end of the semester, but their work on the dozen-galaxy sample is intertwined. Thompson is measuring the radius of each galaxy and figuring out how bright it is at the center and edges.

He’s “taking the radii, putting it through a program that’s already been written, getting these effective values for these radii, then trying to understand how the system is actually producing these radii,” Thompson says.

Valdez, meanwhile, is concerned with the mass of the stars in the galaxies. “I have to look at the ages of these galaxies, and I have to look at dust attenuation,” or the way that dust filters light as it reaches the telescope, he says.

For both seniors, the research involves poring over work that other astronomers have conducted, understanding what previous thesis students have done, and writing codes that form raw data from the telescope images into a model that explains the galaxy’s characteristics.

“You’re going back and essentially revising this code, leaving in your footprints and comments that point to what [piece of code] does what, in addition to when it works,” Thompson says. “Those are the moments when you’re like, ‘Awesome!’”

“It feels good to leave your footprint for upcoming years.”

Thomson’s and Valdez’s efforts have supported and added detail to conclusions that other astronomers have reached, and their analysis has added information that will help astronomers infer how much mass the stars in each galaxy have, as well as the stars’ ages and other characteristics.

So why do the dozen galaxies have such fast outflows? They’re “compact starburst galaxies,” Valdez says. “They have a relatively small volume, and they have lots of stars being formed at an abnormally fast pace. There’s all sorts of properties that are implied from those two characteristics that result in the higher outflows.”

The project has given Thompson and Valdez the chance to present their research and join a larger community of scientists. In October, they presented a poster at SACNAS, the National Diversity in STEM Conference.

Cristopher Thompson and Kingdell Valdez discuss a physics problem in a Carnegie Science Hall physics lab. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“When I got there I was like, I didn’t know this many people of color studied STEM,” Valdez says. “It was a great relief, especially being here at Bates. Oftentimes we’re the only ones in our classrooms that are people of color studying physics.”

At the end of summer 2019, when the Space Telescope Science Institute grant period ends, Thompson’s and Valdez’s work will be key to a paper Diamond-Stanic will submit to The Astrophysical Journal.

“It feels good to be able to contribute something to Aleks’s lab, to leave your footprint for upcoming years,” Thompson says.

“We’re also standing on the shoulders of giants,” Valdez adds. “There are others who have done lots of work with Aleks that we’re piggybacking off of, but also building on top of.

“There’s a good mixture of relying on the past but looking towards the future.”