When the HIV/AIDS crisis emerged in Maine three decades ago, many residents didn’t realize it was a problem.

“People in Maine, whether they were queer or not, viewed themselves as immune and separate from HIV/AIDS, because they conceptualized it as an urban phenomenon,” says Ian Erickson ’18 of St. Albans, Vt.

But activists — most of them serving LGBTQ communities — knew about the disease almost as soon as it became widespread in the early 1980s, and they mobilized to help people prevent and manage it, whether they lived in Portland or northern Aroostook County.

For his senior honors thesis in politics, Erickson did a case study of HIV/AIDS-related activism in rural Maine in the 1980s and 1990s. By looking at a trove of meeting minutes, public service announcements, press releases, posters, pictures, and government documents at the Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine at the University of Southern Maine, he got a sense of the strategies that activist groups used to educate and advocate. And he learned about how they conceived of themselves and their work.

His adviser, Associate Professor of Politics Stephen Engel, believes that Erickson is poised to make inroads on a topic that scholars of political sociology and LGBTQ studies have ignored. “He’s bringing to the foreground a lot of history that has not been systematically covered,” Engel says.

Erickson, who recently presented his research as part of programming surrounding the Bates production of Angels in America, hopes his work sheds more light on the lives of rural Mainers during a particular political moment, especially since rurality is often painted with a broad brush today.

With his honors thesis research, Ian Erickson is “bringing to the foreground a lot of history that has not been systematically covered,” says his adviser, Professor of Politics Stephen Engel. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“A lot of people assume rural areas are conservative and unfriendly places to all of these different identity groups,” he says. “I was interested in dislodging that notion. It’s true in some respects that rural places are more conservative, but I thought it was interesting to take it beyond these heavily partisan narratives and look at actual lived experiences.”

Erickson came to the idea of studying AIDS activism by delving into rural queer studies, an emerging field that looks at the experiences of LGBTQ people who don’t live in cities. The approach challenges “metronormativity,” the idea that LGBTQ people can only live happily in cities, and those who live in the country either stay there unhappily or are preparing to migrate to cities.

Though HIV/AIDS doesn’t affect only LGBTQ people, Erickson focused on the disease after he realized there weren’t many historical accounts of how rural Maine was affected by the pandemic.

As he read and researched, Erickson found that ideas about AIDS contributed to metronormativity.

“When you apply AIDS, it’s, ‘You only go back to your rural hometown to die,’” he says. “It’s a cycle of migration and movement and life that posits the city as being a queer utopia and rural areas as being a place of secrecy and silence and loneliness.”

Activist groups in rural Maine — and there were a surprising number of them, Erickson says — directly challenged that narrative.

Almost from the beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis, they worked to persuade people who lived in the central Maine city of Bangor that AIDS wasn’t just a Boston or a Portland problem, and people in smaller towns that it wasn’t just a Bangor problem.

Some groups, like the Eastern Maine AIDS Network, raised awareness by making it clear that AIDS did not only affect LGBTQ people — though the “de-gaying” of AIDS had the unintended consequence of erasing the experiences of LGBTQ people, Erickson says.

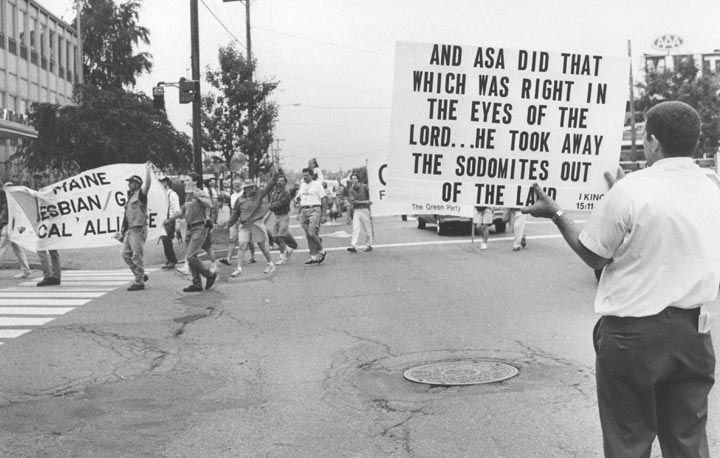

Members of the Maine Lesbian/Gay Political Alliance march past a protester during a pride parade in Bangor in 1993. (Bangor Daily News)

Like such urban organizations as ACT UP, which had two chapters in Maine, groups like the Eastern Maine AIDS Network and the Down East AIDS Network created community resources and held marches and vigils. But they also organized transportation to get people to medical care.

Northern Lambda Nord, which worked in northern Maine and Quebec and published materials in both English and French, helped people network and served as an information clearinghouse. In this way, the group challenged another narrative about rural LGBTQ people: that they were isolated and therefore lonely.

LGBTQ people in rural areas weren’t all that isolated, Erickson says. They were well-aware of national trends and had access to information and medical care, thanks in part to Northern Lambda Nord’s and other groups’ efforts.

And they didn’t consider being isolated a bad thing in the first place. At the archive, Erickson saw letters from out of state to Northern Lambda Nord, asking what it was like to be gay in northern Maine. The answer was often that there was a growing community and a live-and-let-live attitude.

“These people were crafting really specific communities, but they weren’t doing it because they didn’t want to be isolated,” he says. “They loved being isolated.”

Erickson thinks a more potent challenge is loneliness, the danger of not being able to talk to or connect with anybody like oneself. In addition to providing services, Northern Lambda Nord worked to build a community — people could call its phone line to get information about HIV/AIDS, but also to be connected to other people.

“Community-building, phone lines, connecting people to people — those combat loneliness,” Erickson says. “That’s a unique aspect of rural HIV/AIDS activism.”