Collection Highlights: Contest by William Pope.L

I was thinking about the way people use bigoted language. It’s almost a physical act. It’s like you are throwing something at someone. I began doing these experiments where I would just write something and think about the delivery of it. According to how you wrote it, it could be a slogan, or perhaps something even more indifferent, a statement. Is this being said as an accusation? A description? 1

Pope.L

Throughout his work, Pope.L explores race, labor, capitalism, and materiality while foregrounding the bodily experience to render ideas more visceral. Though most notably celebrated for his performance art, multidisciplinary artist Pope.L was equally invested in writing. In fact, poetry was Pope.L’s first introduction to creative expression. In a 1989 BOMB Magazine interview with Martha Wilson, the artist ruminates on his early memories caught in the rapture of spoken poetry in his kitchen. He recounts his mother and aunt quoting Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes, “laughing and bubbling it up. It was neat. Then my Aunt or my Uncle would respond, making up their own lines. And it would fly like that. Like freestyling rap it would take on a life of its own.”2 From a young age, Pope.L sensed the power, joy, and creativity that stemmed from the written word. As a burgeoning artist freshly graduated from Montclair State University in the 1970s, Pope. L continued to dedicate himself to poetry, more so out of necessity; “I knew I was going to be as poor out of school as I was while in school. Writing was a very portable thing I could do.”3

Most potent in these anecdotes for me are the connections that reveal themselves between writing and physicality. The poems introduced to Pope.L early in his life were not stagnant, two-dimensional texts tied down to a sheet of paper. Rather, they were charged with life and given shape, form, and breath; The vibrating tremor of his aunt’s voice and her oscillating breath mediated by the acoustics of his kitchen created a notion of language for Pope. L that was palpable, bodily, and site-specific. Furthermore, his proclivity for writing’s portable quality highlights his negation of object or artifice for a preference for what is always available–the body, our surroundings, a pen, some paper. Writing’s stripped down nature and its relationship to movement as something that you can carry with you anywhere correlates directly to its own physical practice of drawing ink across paper. Even when not explicitly enacted through the body, much of Pope.L’s work is charged with a sizzling physicality, including his text-paintings, like this one in the Bates Museum of Art’s collection.

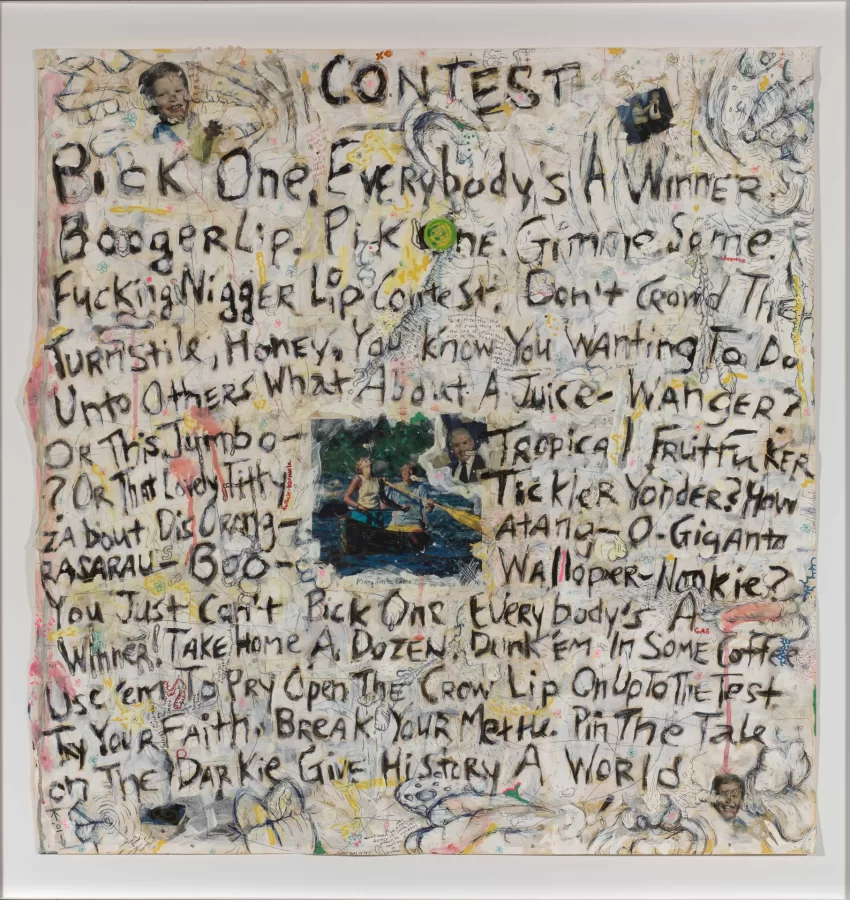

At first glance, Contest appears as a text more than anything else. Stark black words seep up from their murky-white backdrop as if wet and soggy. The letters are oddly shaped, slightly smeared by white paint, and they bob up and down in wavering bands. From a distance, this work transmits light-heartedness and joy. Its white backdrop is laced and dotted with bright pastel colors, and a photograph in the center depicts a man and a woman laughing on a rowboat in the sunshine. Not long into looking at this work, however, the words crystallize and quickly complicate the collage’s seemingly joyful temperament. The text is an incongruous assemblage of words spliced with racial slurs, made-up words, and stunted with question marks. It is hard to discern, and incites uncomfortability and curiosity.

Searching for more information, I look closer to find pen illustrations of body parts: ears, hands, and many lips, large and pillowy. Small cut-out faces of white boys smile at me, in a frozen and creepy sort of way. In miniscule writing, addendums hide: such as, under the rowboat image, “Many Contests Come by Boat.” Scanning over the black words again, I respond viscerally; the fragmented statements are chucked at me in short spurts. As a whole, the work’s layered haziness, and its jumbled, mixed-up pot of words and images elicit a feeling of troubled frenzy. It is alive in movement and cluttered with sound. The frayed left edge of the work tells us the paper was once torn. Pink paint ceaselessly drips. Lips pucker. Mouths pry open. Hard T’s cut the air. Suddenly the whole work feels like it’s going to suck me into its cloudy, cacophonous mess.

“It’s not that I have the arrogance to believe that I know what should be done,” Pope.L told Martha Wilson in the BOMB Magazine interview. “In fact, I’m afraid of the responsibility, but something should be done. And if I can construct works that allow people to enter themselves, thus, enter the mess – then it’s a collaboration and maybe, possibly, who knows, why not – I’ve nudged something.” In this work, Pope.L pulls the viewer–their entire sensing and bodily self–into the complexity of racism, consumerism, and capitalism. He explores the sonority and movement of bigoted language and magnifies racial stereotypes. The large puckering lips, for example, seem to depict the stereotype that Black people have big lips. “Everybody’s A Winner! Take Home A Dozen.” seems to be a nod to consumerist-oriented American game shows. The small addendum “Many Contests Come by Boat” might reference the arrival of Europeans by boat, the stealing of Indigenous peoples’ land, and the ensuing and ongoing cycle of violence and exploitation. Playing with both poeticism and abstraction, Pope.L seeks to describe the feeling and the effect of hateful language over its literal meaning or direct references.

As a dance-artist interested in durational and experimental modes of performance, I first came across Pope.L’s work through personal research. As he also happened to have been a Professor of Theater and Rhetoric at Bates College from 1990 to 2006, his presence echoes in the very spaces I occupy everyday. As an early museum intern, I remember filling up with intrigue upon hearing about how Pope.L’s use of everyday objects can pose a challenge for museum preservation. When deciding on a work to write about that spoke to me in the collection, a Pope.L work seemed obvious to return to three semesters later, as this artist has continuously captured my curiosity.

While this work is in our collection, Pope.L is most well-known for his New York City crawls (1978-2001). In these provocative disruptions of public space, the artist drags himself against hot summer asphalt, moving in a contradictory way to the monotonous churning of a great corporate machine. Through these crawls, the artist practiced obtaining a new perspective and prompted passersby to also shift their awareness downwards. Embodying a kind of horizontality that referenced the growing houseless population of the time–to which Pope.L was closely related with his father and aunt living on the streets– Pope.L attempted to bring awareness to a rising and personal issue.4 In realizing this work, he wondered, “Is there a way to align myself with a people who have less than I do (materially) without making fun of them? I decided to literally put myself in the place of someone who might be homeless and on the street. I wanted to get inside that body. Like, what does it feel like?”5

Pope.L takes an extreme approach to kinesthetic empathy and invites his audience to experience his art in similarly visceral ways. He is intent on shaking viewers up, probing bodily reactions and writing in bold those taboo issues that are sometimes easier to ignore. Pope.L reminds us that these issues exist whether we decide to look at them or not, and shows us that their effects are often stored and left to fester in the body. As a dance-artist, it was Pope.L’s commitment to embodying these complex issues that first drew me into his work. As an audience member, now having spent time with this piece in the Bates Museum of Art’s collection, I am left contemplating my role in perceiving it. Are people interacting with this work just as integral to its meaning as its own physical components–its text, illustrations, and magazine cut-outs? Through its leaking and disruptive nature, Contest incites dialogue, interaction, and builds an interconnected relationship between audience and art–ultimately crafting an experience of viewing that latches on to us, and one that is, afterwards, hard to shed.

- Basciano, Oliver, “I’m not Jeff Koons!’ – the endurance crawls, weird texts and guerrilla brilliance of Pope.L,” The Guardian, 2021. ↩︎

- Wilson, Martha, “William Pope.L,” BOMB Magazine, 1989. ↩︎

- Basciano, “I’m not Jeff Koons!” The Guardian, 2021. ↩︎

- “Pope.L. Is Making a Commitment to Art.” Louisiana Channel on YouTube, May 18, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTs5QkK20M4. ↩︎

- Wilson, Martha, “William Pope.L,” BOMB Magazine, 1989. ↩︎