Senior Thesis Exhibition 2020

Haiyao Tian, My Room #01, 2019, digital photograph, 13 x 19 inches

Featured through June 7, 2020

Since its dedication in 1986, The Bates College Museum of Art has maintained a special relationship with the college’s Department of Art & Visual Culture. Part of this is a commitment to supporting the work of Bates students through our Annual Senior Thesis Exhibition. The exhibition highlights work selected from the thesis projects of graduating seniors majoring in Studio Art.

Thesis projects vary from student to student, each pursuing an individual interest. The emphasis of the program is on creating a cohesive body of related works through sustained studio practice and critical inquiry. The year-long process is overseen by Art and Visual Culture faculty, and culminates in this exhibition.

Student thesis work is displayed below and includes thesis statements and a gallery of images for each artist. To view the 2020 exhibition, click on individual artist’s names and scroll down to read their statement and see a selection of artwork. An illustrated exhibition brochure is downloadable by clicking here.

+Ariel Abonizio

Sometimes, things feel more present when they are gone – like a missing family member, an abandoned house, or a single sock without its mate. In my life, absences often resemble apparitions, events from my past that linger on despite not being actually there. When something is forgotten, I can still feel its contours, as something still remains. It is as if silence could be louder than words.

Other times, the opposite happens: presence is unfulfilling and resembles absence. It is like seeing a fake smile or being in a house full of strangers. The moments when presence vanishes and turns to nothing are more haunting than ghosts.

And yet, within this atmosphere of loss and grieving, the paradox of presence and absence also evokes comedy. In my artistic practice I try to capture the hole in every donut. Through photographs, videos, and installations, I document what is not there. I make copies of a reality that never truly existed, not even in my dreams – I make unicorns.

About unicorns, Greek philosopher Pliny unironically wrote: “It is the fiercest animal, and it is impossible to capture one alive.” Similarly, presence and absence cannot be directly apprehended. To see a unicorn, you first have to close your eyes.

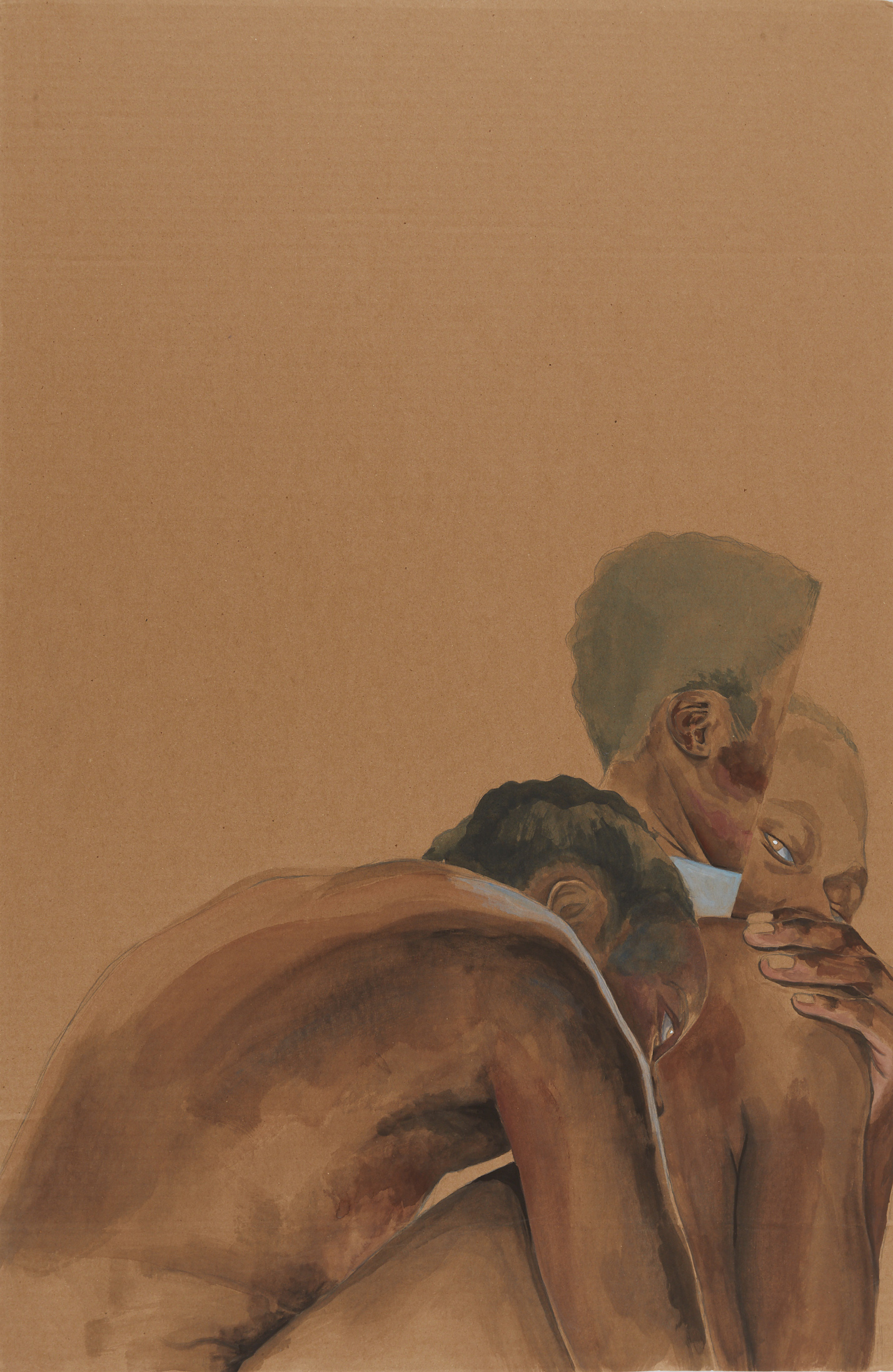

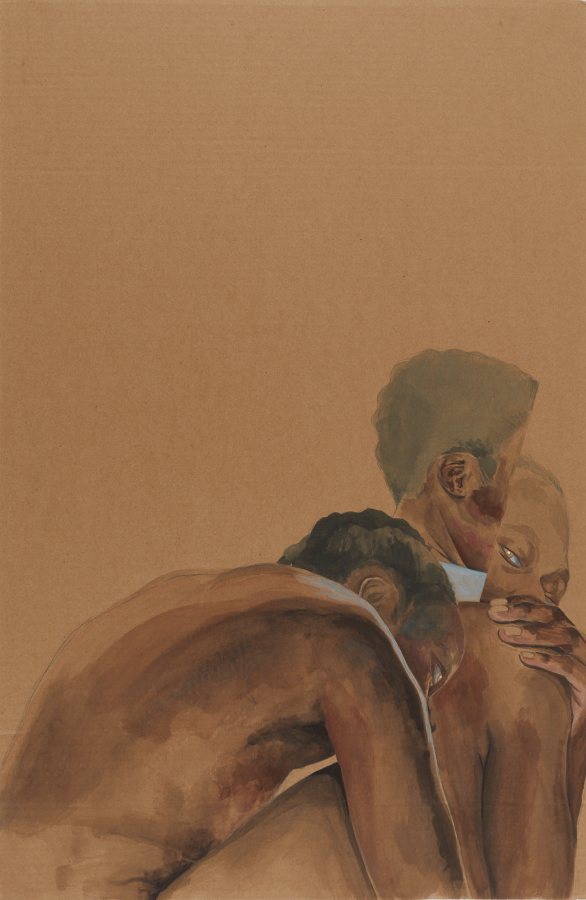

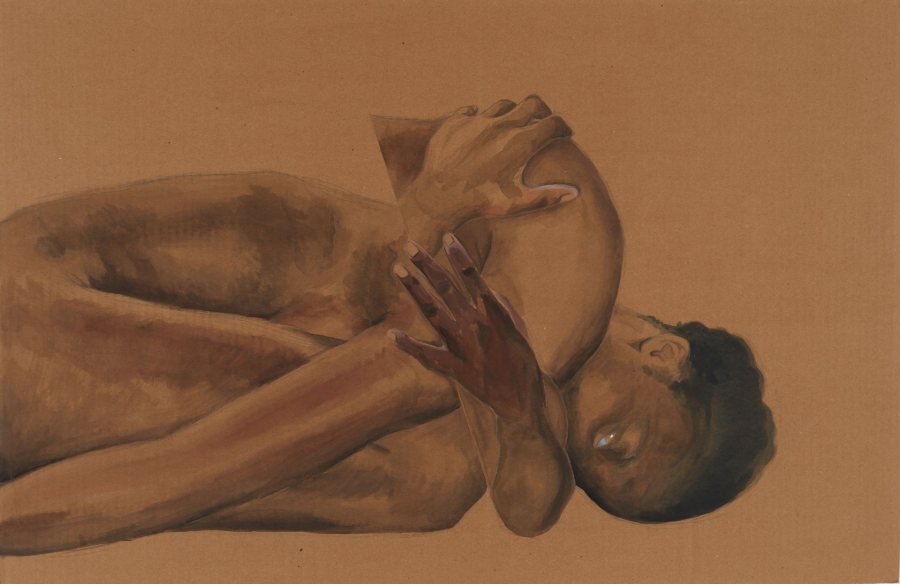

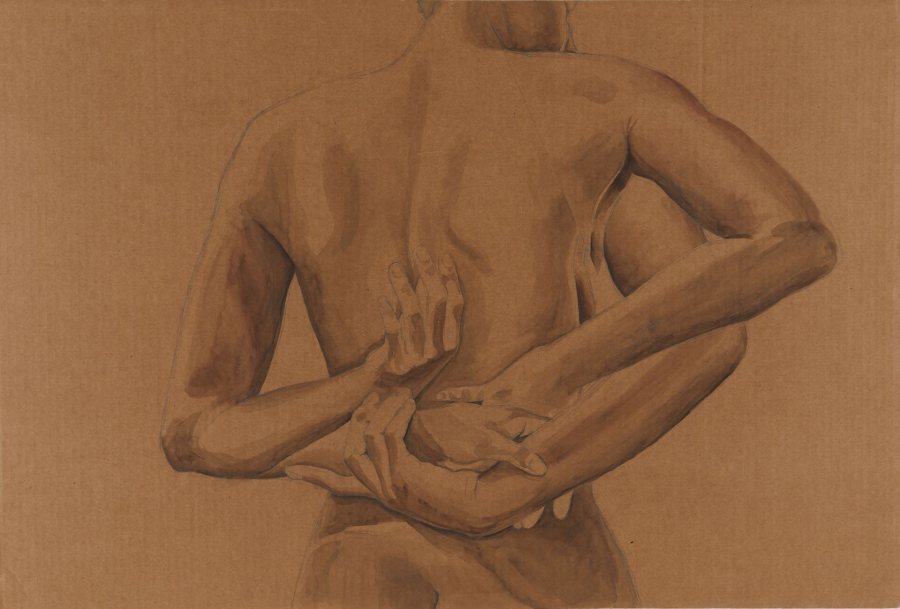

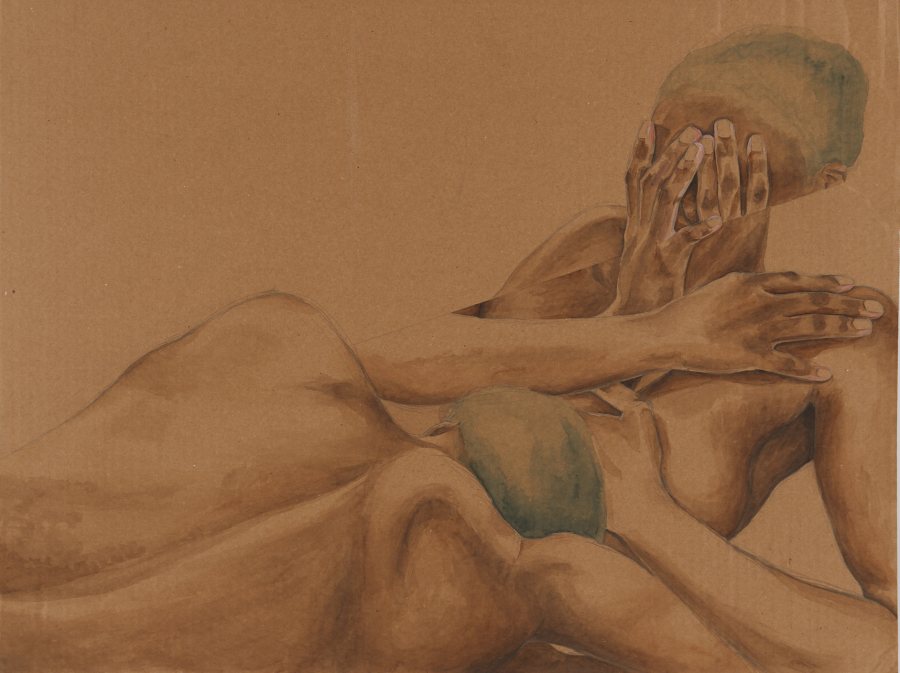

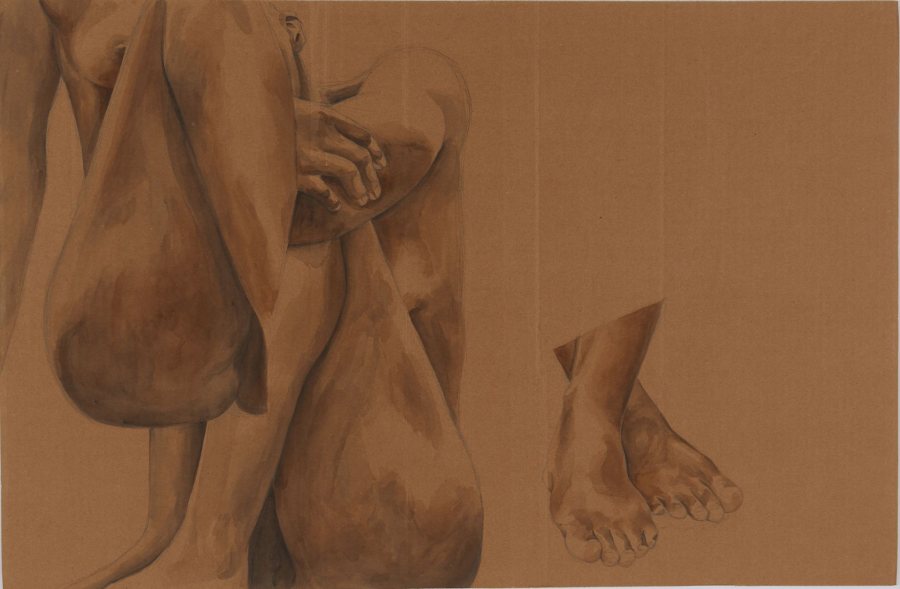

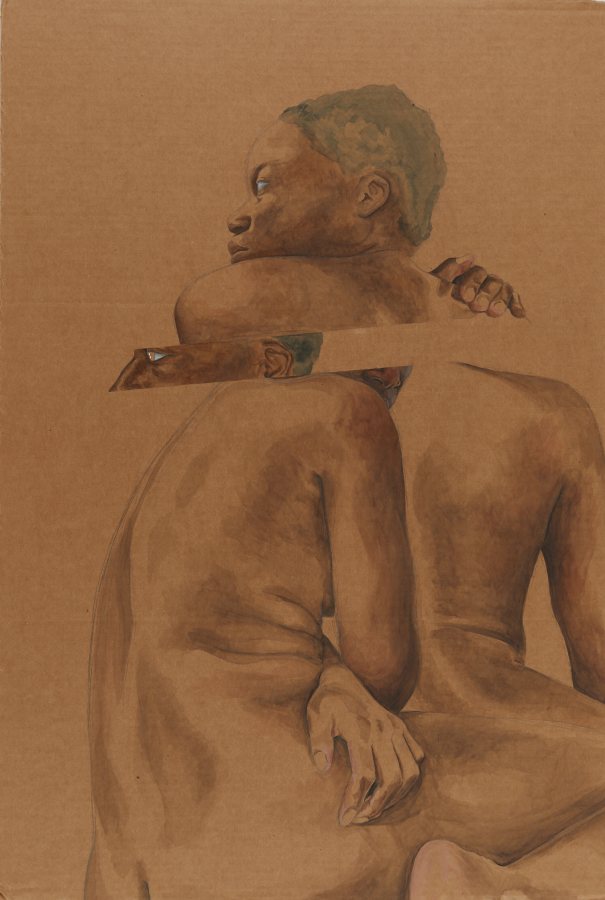

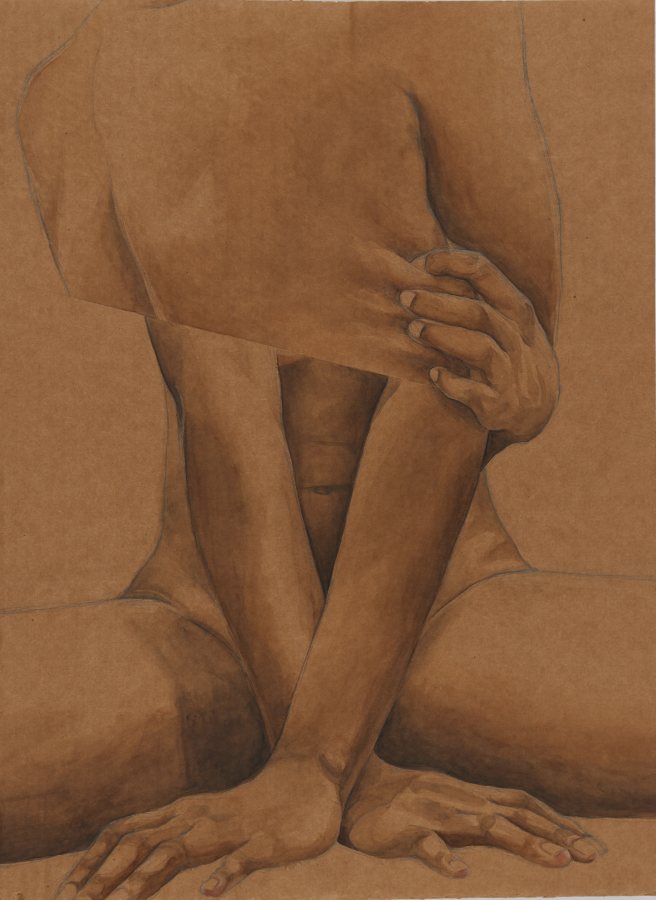

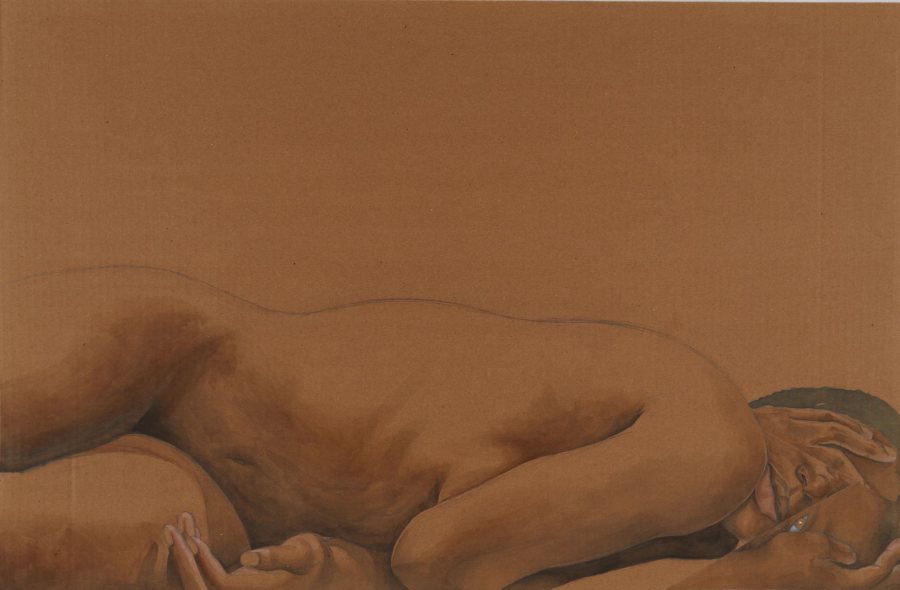

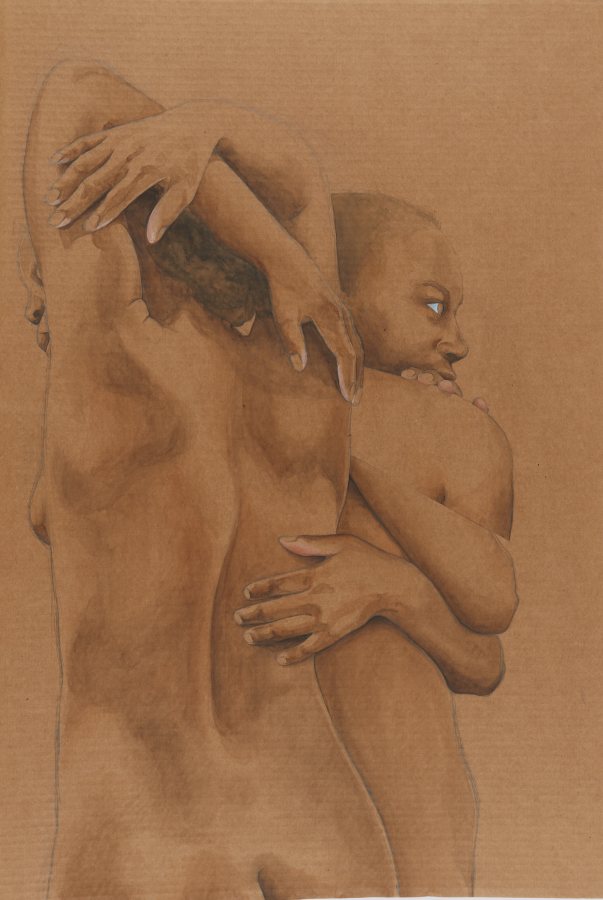

+Mayele Alognon

Is there one authentic version of self or are there multiple—even infinite—versions that are all equally authentic? My work investigates this question, on the assumption that the latter is closest to the truth. I paint to validate all of these versions, making nude self-portraits on cardboard as an exploration of the multiplicity of my being, as well as experimentation of how surface can transform object and the inverse.

I paint my body in multiple instances to consider the number of identities that occupy my one being. It is not sufficient to paint only one version or a singular figure to represent myself, because I am never one single thing; I am never just embodying one aspect of my identity, nor drawing from a single emotion or experience. I am African American. I am female. I am an immigrant. I am a daughter. I am a sister. I try to paint myself in my entirety, keeping in mind the vulnerability, the shame and the excitement that are all present within the process of creating this work.

Although the concept of wholeness is a significant component of my paintings, I paint my body in fragments. Parts of me are hidden, obscured or spliced. In some paintings, it may be difficult to tell where one figure begins and where another ends, because with this multifaceted process comes complexity and ambiguity.

First, I take photos of myself, then I choose three or four that have similar focus either on a specific body part or indefinite emotion that I attempt to work through. Next, I make a line drawing on cardboard, and finally, I begin to paint with gouache, an opaque type of watercolor. The paintings are mostly gouache on cardboard, a textured and imperfect surface.

I use cardboard for a few reasons. I am interested in reusing materials and finding a purpose for items that are often thrown out without a second thought. I am also interested in seeing how medium and surface work off of each other. The meaning of a painting can change knowing the previous uses of the surface and its near fate as garbage. Mainly, it is my goal for the brown gouache to look as if it is emerging from the cardboard, so that the materials normalize blackness and black skin as well as the imperfections, roughness, complexity and ultimately the beauty that it inherently carries.

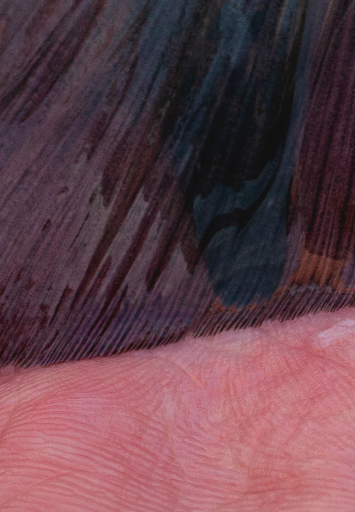

+Nick Eaton

Fly fishing and photography have taught me similar things; patience, respect, and sensitivity. Throughout my work, I use both of these passions to examine my relationship with nature, and the beauty that can be seen when an effort is made to stop and observe.

The process of producing photographs of a fish in its own habitat is challenging. In order to get these shots, I first had to catch the fish using a hand-tied fly. After securing the fish, I held it gently in the water with its scales visible to the camera, in order to keep its gills submerged. As I stood there in cold, waist-deep water with wet, salty hands trying to get the perfect shot, I admired the sheer magnificence and strength of this fish. As a fly fisherman, it is very important to me to make every effort to ensure long-term health of the beautiful fish I am lucky enough to encounter, so I work quickly and then release the fish back into the water.

Catching the fish is the culminating event at the end of long sessions at my table creating life-like flies out of elk and deer hair, rabbit fur, and hen feathers. This entire process adds another personal dimension to my work.

My photographs of Maine-caught striped bass are intentionally printed in a small format to bring the viewer in closer, to examine the intimate nature of a human hand caressing the fish. In addition to intimate photographs, I also work on a larger-than-life scale. The macro-photographs of hand-tied flies unpack and reveal layers of detail that would be nearly invisible to the naked-eye. Whether looking at the natural iridescent color on the fish’s scales, unique pattern of the human hand, or the coarse elk hair in the fly, all these subjects hold unique details that help tell their story.

By contributing towards the appreciation of the intimate relationship that is shared between fly fishers and their catch-and-release fishery, I aim to complicate something that is too often associated with hypermasculinity, killing, and disrespect for the environment.

Fly fishing is about so much more than just catching fish. It is a practice where everything is intertwined; from tying the flies by hand, to understanding entomology and the weather in order to know when to use a certain type of fly. Those who fly fish are conservationists committed to ensuring a healthy environment and ecosystem, keeping our rivers running cold, and preserving fish stocks for generations to come.

+Celia Feal-Staub

I am motivated by an object’s intrinsic ability to affect us and our experiences. My work in clay began with function: mugs, bowls, pitchers, jars, plates, and other utilitarian objects to use in one’s everyday life. As I learned how to throw functional pots on the wheel, for me the practice became a form of complete and utter control. I controlled the speed of the wheel, and the pressure of my hand which pushed the clay wall out, creating a different curve each time.

Now I have moved away from functional pottery and from this intense desire for perfection. I focus on allowing myself to give up such extreme control. I now give myself the freedom to fully experiment with form, and also with collapse. I allow my feelings of anxiety and desperation and joy and compassion to seep into my work, rather than barricading emotion out.

I use varying levels of distortion, inflation, and deflation in a tactile way to explore the concept of what an object’s force can be. When I work, I think about breath – deep, calm, truly content breath, or panicked, shallow, and rapid breath. I bring this into my work in a literal sense, by breathing into some of my vessels and removing the air from others.

The human-esque, emotive nature of these vessels is what compels me to make more. With a squeeze of the vessel’s neck, or push to the belly, they take on entirely new forms – perhaps forms of people in love, listening deeply to each other, enveloped in hatred, rejection, longing, acceptance or the lack of it, or empathy.

What do you see? What do you feel? I am fascinated by the way that meanings and narratives are assigned to my work.

I think of my collection of vessels as a visual calendar and journal. Every touch, indent, or deflation I make represents a specific moment in time. As I make more and more of these vessels, I am increasingly drawn to what happens when the quantity of vessels nears hundreds, and my own time and labor are explicitly represented. One vessel on its own does not evoke as many stories or emotions, but when the vessels amass, relationship dynamics and narratives begin to emerge. The vessels collapse into each other to create not merely a collection of items, but also one large cohesive moment.

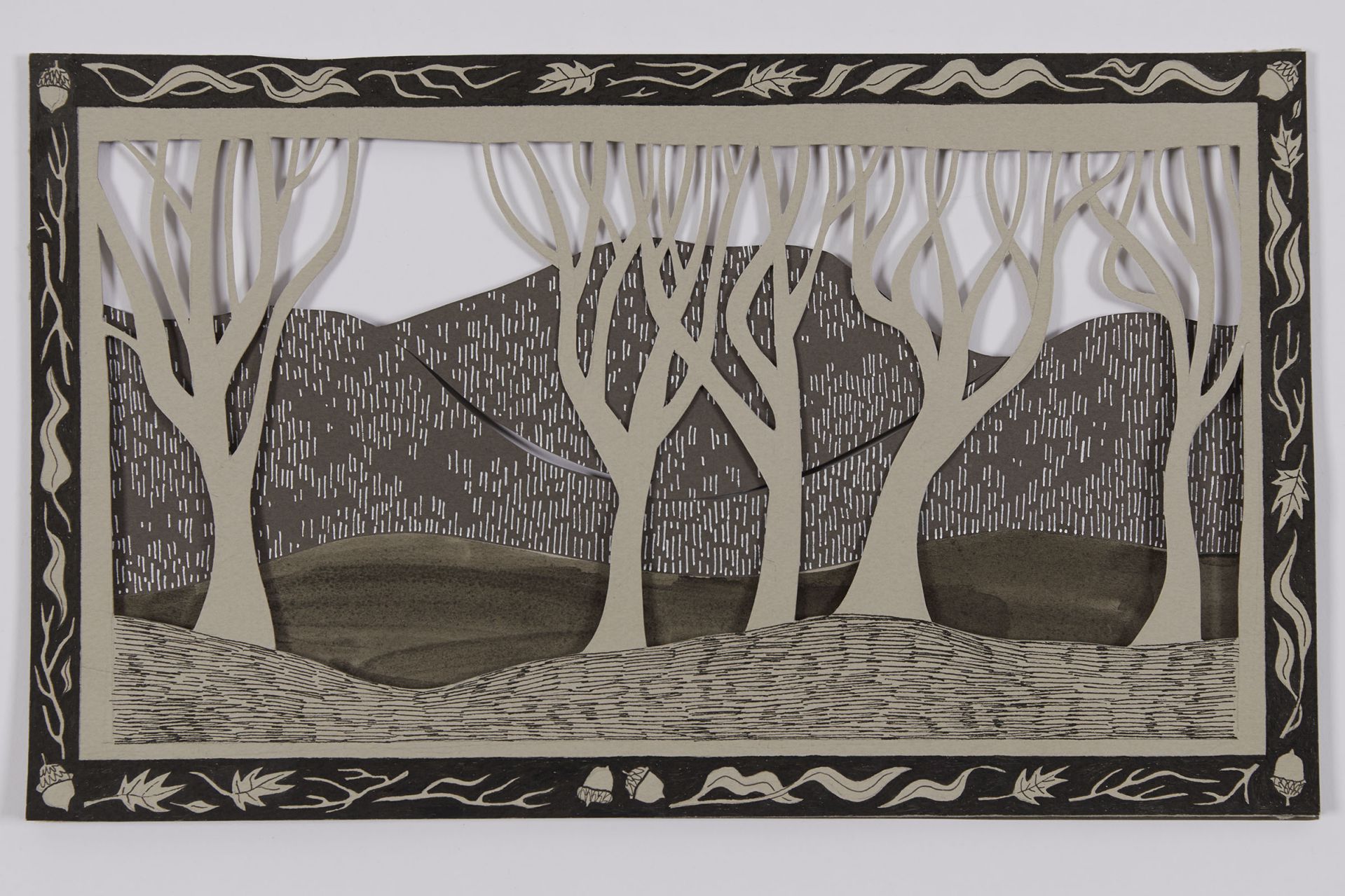

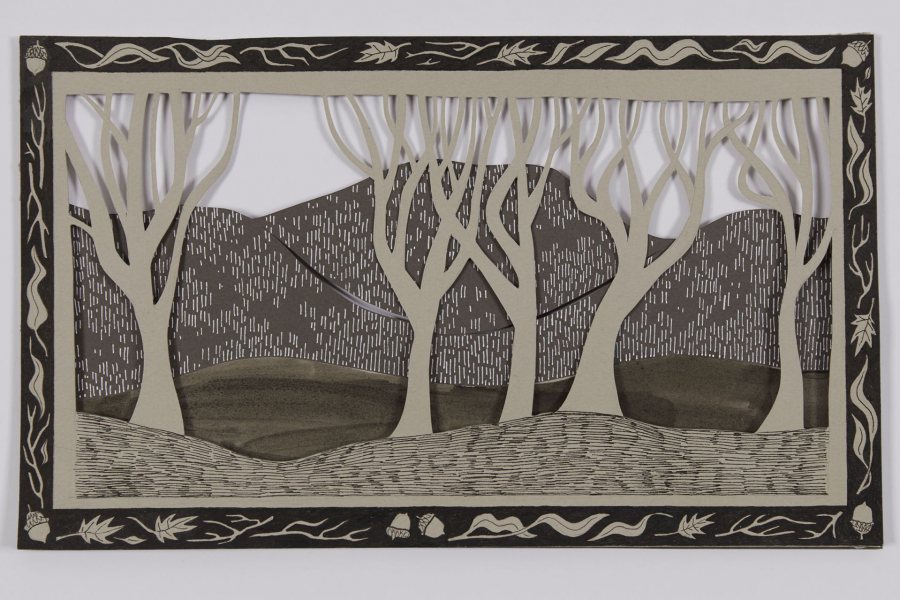

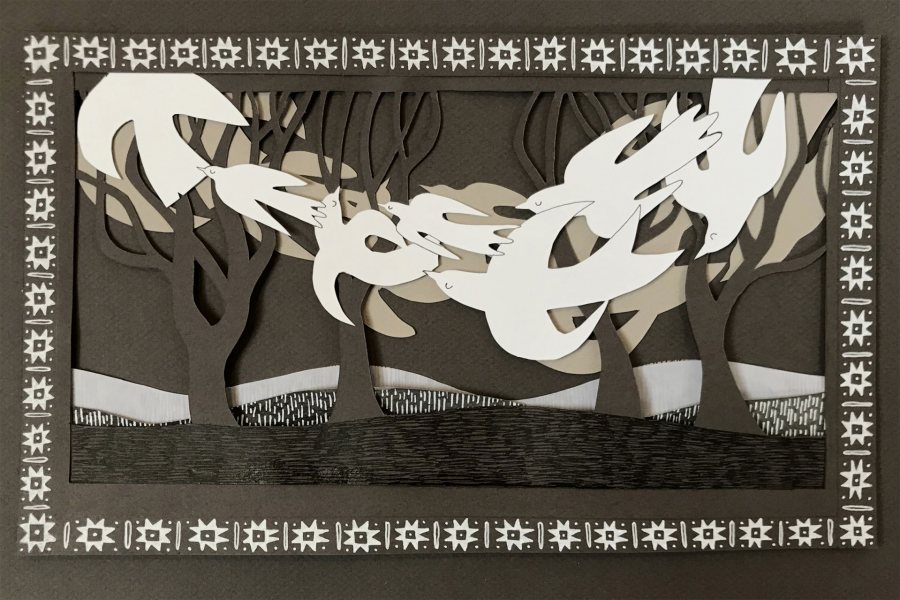

+Sophie Gerry

While working in the studio I ask questions about my relationship to home. How do I perceive, experience, and remember the landscapes I have spent my life in? How do I move through those places and why do they feel so comfortable? These questions, and others like them, have guided me in identifying nuances in natural landscapes and personal memory.

I develop artwork that emphasizes multidimensional, expansive views of the natural world based on the woods and mountains surrounding my hometown. These landscapes, botanical studies, and gently moving mobiles begin to capture the visual experience of moving through a natural setting.

I cut and fold weighted, colored, and textured papers. I illustrate and pattern these papers using pens, pencils, ink washes, and cut-out shapes. Placing cutout forms on top of and in front of each other logically leads to working with paper mobiles. Layered images and moving mobiles both ask to be looked at from different angles. Changing the levels and positions of these pieces, reveals new shadows and versions of the imagery.

I have looked to the installation work and written statements of the Danish-Islandic artist, Olafur Eliasson. Much of Eliasson’s work is based on perceptions of space. He writes about the way movement through space strengthens connection and creates vivid sensory memories of specific locations.

My work is both irregular and controlled, detailed and simple. I have studied Norwegian folk art, and modern and contemporary Finnish and Swedish design. The roots of this visual and material culture are embedded in Scandinavian life: values such as practicality, simplicity, and sustainability link to appreciating and utilizing local landscapes. In this context I have worked to distill images of complex natural features into simplified and whimsical forms.

I carry mental images of the trail systems that surround my hometown. They sweep through shaded woods and open meadows, and cut across hillsides. I know the contours of the mountains and can map the turns of each trail. Although my memory of those places is strong, the landscape shifts and evolves with each season. Similarly, my perceptions flicker and change over time. The art I make is my act of remembering. I work to keep in close contact with the places that have so positively impacted me.

+Emma Blair Hall

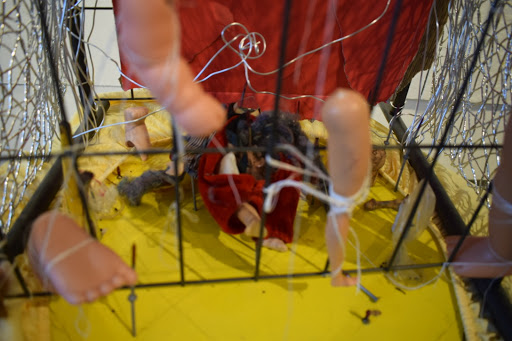

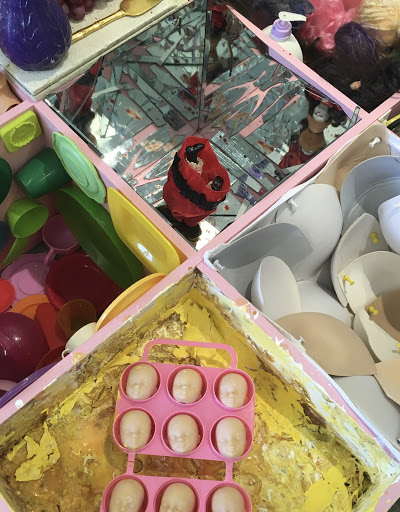

I am a mess maker. Working with my hands, I am interested in the messiness of the human experience. The themes of my work center around my experiences with the instability in lust, love, death, and life. Process is everything to me. I spend a lot of time alone, writing out thoughts and challenging the ways I was taught to look at the world.

All of the materials and objects I use are unwanted, rejected, or forgotten. Sculpting, I combine any number of unwanted objects to capture an emotion or a story that otherwise may not be heard. Some of my favourite materials to work with are tiny plastic toys or articles of clothing. I often think of my skin as cloth. My influences are artists who have created their personal stories, experiences, emotions into these abstract non-verbal interpretations that find homes in different media: such as Jeffrey Chueng, Sandy Skoglund, Ai Wei Wei, Nilüfer Yanya, Vanessa German, Caleb Yono, and Kader Attia.

One of my sculptures is an interpretation of Humpty Dumpty. The bottom half is a coordinated mess of rejected fabrics poorly covered in a gown-like yellow layer. It surrounds a wooden core with an excessively objectified pink interior. However, the pinkness within the core is not contained. It falls onto the path in front of it leading to the egg cartons, broken egg shells, horses, and legs that reside on this path too. Shoes circle around it, starting at where the path ends, waiting to walk across the eggshells. Choose your pair wisely.

A doll dressed as a ladybug is directly above the wooden core. It lies ripped apart like a dissected bug with a jagged piece of mirror over its face. The bloody nails that penetrate it from underneath form a circle around it. It is almost playful, like when little girls decapitate their dolls after aggressively chopping off all their hair. Surrounding the doll and the bloody nails is a larger cage. Dolls’ limbs are tied onto this cage. I’m not sure if they are lost, in the process of falling, or settling in. Either way, defining these as lost or found limbs is up to the viewer, not even the King’s horses or the King’s men can put you back together again. (Also if we really wanted Humpty Dumpty to be put back together again, we should have sent literally anyone other than “all the King’s men”.) There is a wired outline of a torso inside this cage. A round mirror rests on the top of the cage, facing downwards, towards the dissected doll’s own mirrored face. At the very top: the unremarkable doll head rest, almost lost in its own hairy mess.

All of it sits outside a dumpster now, waiting to be collected.

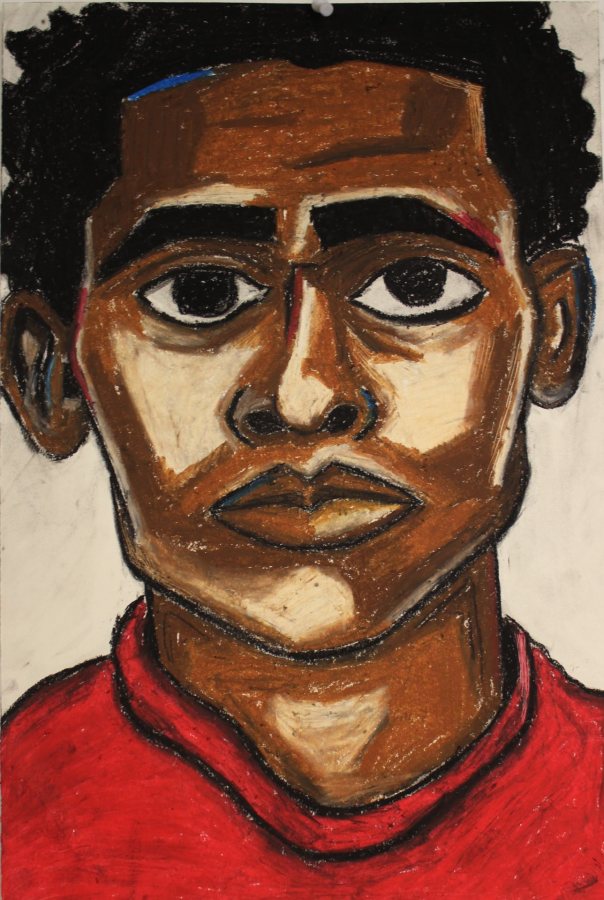

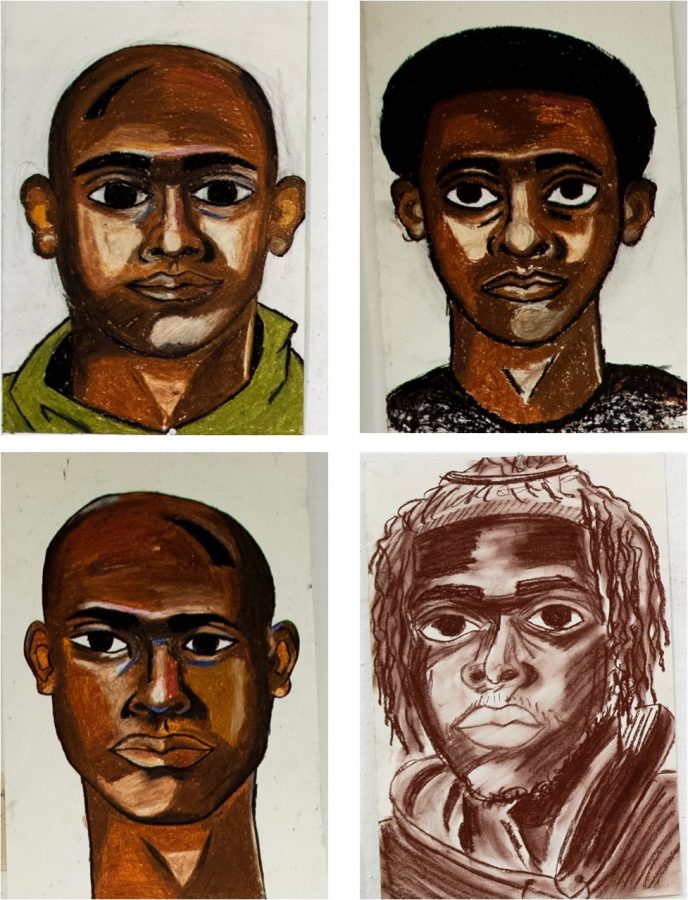

+Mike Hogue

I make portraits of brown and black faces to unpack the history of portraits. Throughout history, portraits of brown and black faces were often described as caricatures, presenting brown and black people as simple-minded and often subjugated. As a black man, I often feel underrepresented throughout daily life. Because of this I strive to activate and challenge the audience not only to confront the art, but the subject as well.

My process of trying to find which materials to work with has been difficult. I am combining media, including pencil, colored pencil, charcoal, and marker. I find that working within these constrictions gives the portraits a more realistic feel. Terrance Vann and Christopher Clark have been huge inspirations for my work.

Sometimes when I complete a piece, it feels like the subject has a direct gaze with the audience. I think the most successful portraits depict a direct gaze with the audience, and this is what I want to challenge the audience with. This direct gaze inspires me because it is forcing the audience to confront the subject–almost as if it is a mug shot. I would like to continue to explore this.

I hope this body of work helps make people feel more at ease with experiencing brown or and black faces, whether it be through art or the real world. In the same way Fredrick Douglass challenged the nation by posing for portraits that portray black freedom and dignity, I hope to challenge my audience to see brown and black people for who they are, rather than what people take them for.

+Mike Jones

My work consists of creating the characters that live in the world I am inventing. Utilizing conceptual fantasy ideas such as magical abilities, dynamic powers and destructive entities, I have constructed a world from my imagination which I call Lezeallion. I have developed particular character archetypes and stylizations from inspirations in the realm of fantasy media. The works from my childhood that influenced me in developing imagery and capturing the viewer include the Mistborn series of epic fantasy novels by Brandon Sanderson and Kuroko no Basuke by Tadatoshi Fujimaki. They provide a model for my vision of characters, stories of action and power, and the development of my world of Lezeallion.

These interpretations are primarily developed as ink drawings. I begin by replicating and re-creating characters from the media I enjoy. This leads to creating my own original characters, backgrounds and stories using my imagination. In addition to ink I also use colored pencils, markers and white gel pens, working to evoke a personality within each character. One of the enjoyments of making my work is creating the visions that I want to see more of in fantasy media and bringing these ideas to life. This can include characters with darker skin or anthropomorphic beings interacting in a human setting.

Focusing on story concepts and the “experience of the character, I find satisfaction in exploring the souls of my creations as real beings who face issues that can be metaphorically or literally relatable. My hope is to provide a path to my imagined world of Lezeallion, whether it is a physical, emotional or spiritual connection, and that the viewer is able to enjoy my drawings aesthetically as well.

+Otis Klingbeil

In a broad sense, my work explores how to represent a specific place on an emotional level. Woodstock, Vermont has been part of my family history for over a century now, a constant anchor in my life. I intend to represent the essence of this place by simplifying and abstracting rural barns around my town.

I work with oil paintings, collage, and three-dimensional paintings, deconstructing the barns to emphasize their architectural and structural elements through clarified planes of color and strong contrast between light and shadow. While my focus is on the abstraction of these familiar structures, it is important to me for them to still be recognizable as buildings.

I work from photos I took in Woodstock, but I am not trying to replicate the images in my work exactly. Instead, my photos are a tool to organize and inform my process. I maintain an emphasis on color composition, primarily using a warm palette of reds, pinks, and yellows. Sometimes I leave my paintings in their two-dimensional form, but other times I cut them into shapes and glue them at differing heights, building them out. I leave the edges exposed so the underbelly is visible, similar to the exposed rafters or support beams of a barn. I change the composition to work the angles; from the front the image is coherent, but it is more fragmented when seen at an angle.

Overall, I think of my work as a series of repetitive studies of these barns, letting each new piece inform the next. I am not so concerned with imperfections in the way I apply paint or make my cuts, instead letting myself be motivated by creating a body of work that is nuanced from a variety of perspectives.

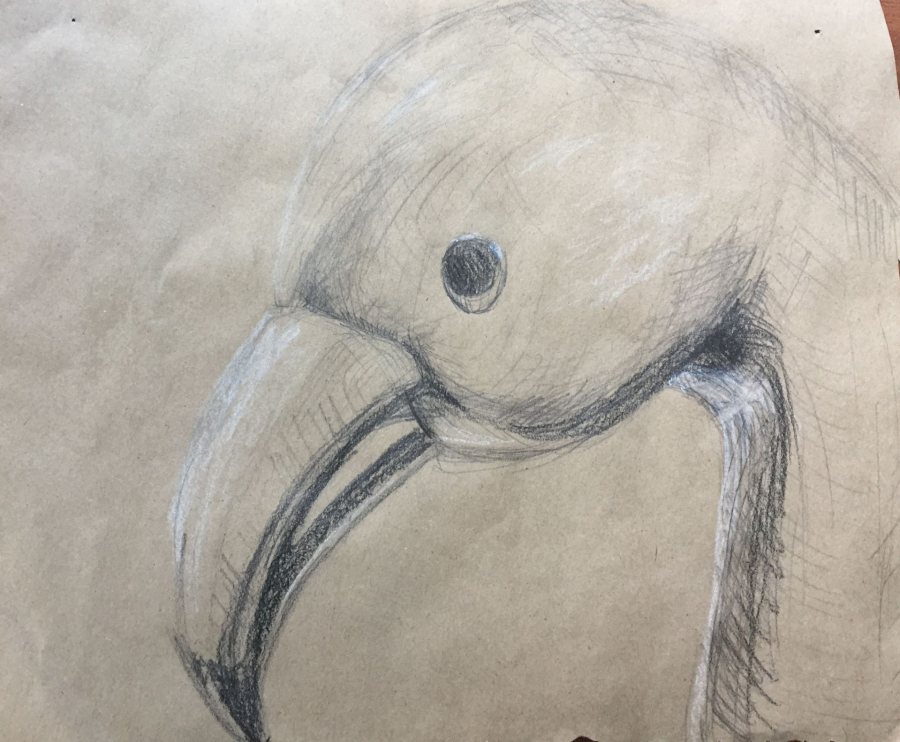

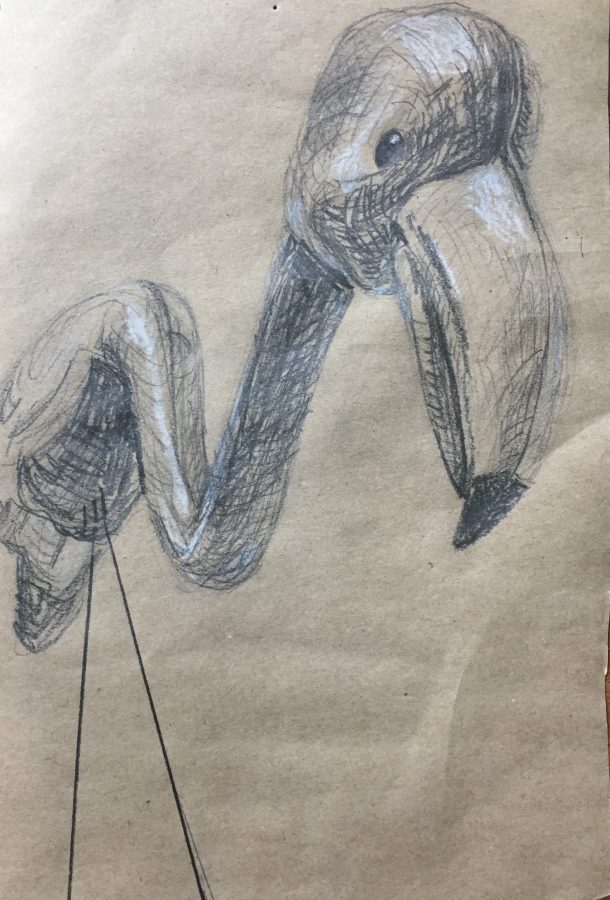

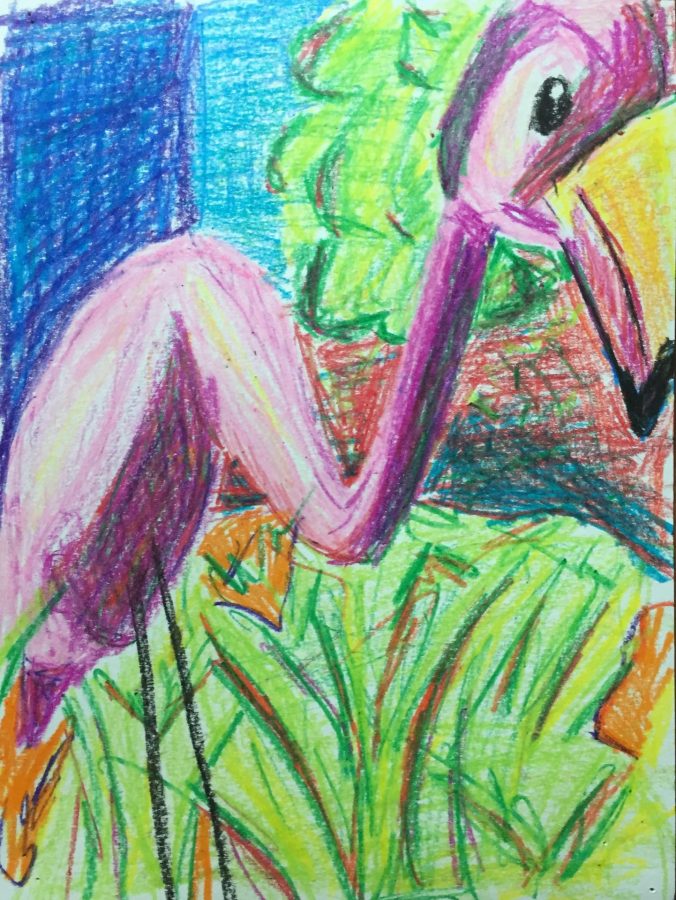

+Eden Rickolt

Flamingos don’t usually live in the United States, but plastic hot pink flamingos are everywhere. I am fascinated by the evolution of this lawn decoration as an American cultural icon. There is an inherent tension in the opposing ways that these creatures, both real and fake, are represented and perceived. Real flamingos are graceful, beautiful, and natural. They are tropical and exotic. They represent wealth and luxury and vacations. Plastic flamingos, on the other hand, are banal and tacky. They are funny and lighthearted. They are campy. They are a prank. Today, they are ironic. Who/what is being made fun of? The consumerism of American culture? Or, is it the alleged tackiness of the lower and middle class?

In any case, I find it interesting that while the symbol remains the same, the meanings of it change. My work was initially inspired by the curiosity of what happens when the visually consistent but symbolically erratic object is physically distorted. Whereas the ornaments are so utterly uniform and lifeless, my flamingos take on an eerie individualism.

With flamingos as the focal point, I create installations using quintessential elements of the American house and yard with the goal of creating new surreal places that are both funny and disturbing. I explore what is actually lurking underneath a veneer of order and innocence. I use a mix of recycled materials such as packing peanuts, bubble wrap, and cardboard to construct my objects. Then I apply paper mache to the form. I also use paint, fabric, and yarn in order to create a bright color palette. I like the idea of my sculptures resembling candy that is so sweet that just looking at it will rot your teeth. In other words, the colors become a parody of comfort and happiness.

My work is influenced by the comical and playful furniture, sculpture, and general aesthetics of designer Katie Stout. Her work helps guide me as I push mine into the realm of the absurd that is both playful and dark. The writings of James Tate influence how I think about the possible stories and moments occurring in the scenes I create. Specifically, his poems in “Return to the City of White Donkeys” inform my process of making surreal work based on distorting the seemingly ordinary. Through these distortions, I hope to challenge simplistic views of the iconized American suburbia by combining a sense of play with theatrical absurdity, and a threatening underbelly that challenges simplistic views of the iconized American suburbia.

+Madeline Schapiro

My work is a garden of permanence. Growing up, I spent every Saturday in the garden. My role was to comb through the soil to remove clay and then sow seeds. As I work today, I find myself in a garden made of red clay. Instead of discarding the clay, I cultivate it by hand, building with earthenware.

I work with earthenware because its red hue is similar to the clay I extracted from the soil. I focus on process and tend to my pieces. I begin by hand rolling the clay, and rake it to remove imperfections, then methodically smooth the piece, before cutting out each slab. Next, I fold and drape the clay, combining walls and smoothing them, leaving traces of my hand in the undulations of each piece.

The surface drawings are inspired by crops I planted as a child including tomatoes, peaches, lemons, and other produce. I am also inspired by 1800’s botanical drawings, Chaos Theory, and the intricate designs of William Morris’s botanical patterns. For example, I use small white dots (akin to seeds) to reference Chaos Theory: the interconnectedness between the white dots represents the chaotic behavior that exists in natural climates and underlying fractal patterns.

Once my pieces are fired, the botanical surfaces are sealed, permanent, ready to be used.

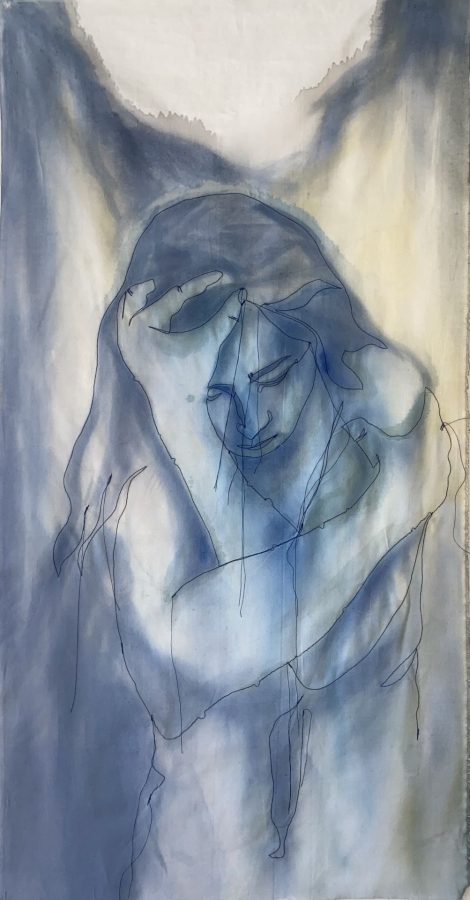

+Grace Smith

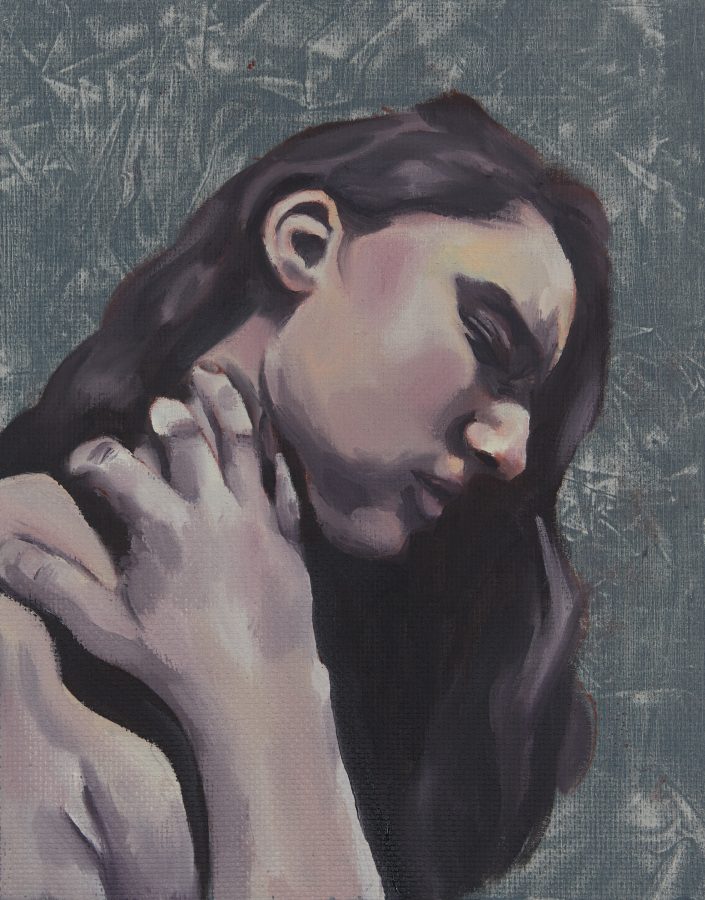

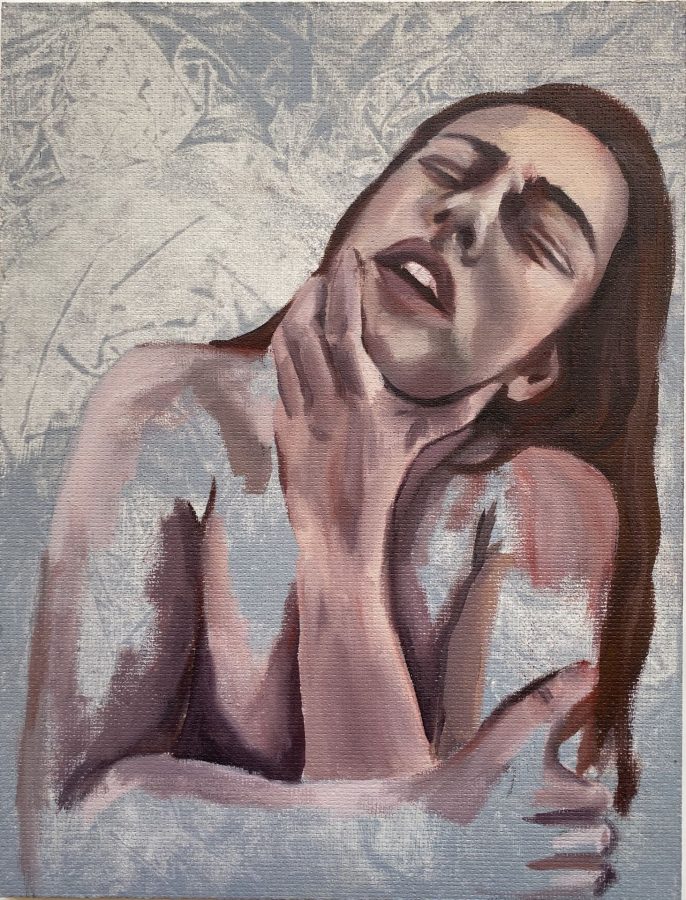

I am aware of intense emotions, anxieties, and the way people communicate through their bodies. I feel an urgency to convey and evoke emotion in my work, and try to better understand my own mental states through my artistic process. The resulting imagery depicts how the pain of experienced emotions manifests in body and mind. My artistic process has helped me work through the confusion, exhaustion, and complexity involved in my life. Most of my portraits move between multiple feelings simultaneously, in an effort to accurately describe how emotions are felt– all at once and often confused.

My work with expressive portraits includes traditional painting on panel, but I also make works that combine sewing, embroidery, and applique on muslin. My research includes looking at the work of Orly Cogan, Egon Schiele, and Gustave Klimt. I consider Cogan’s work for her use of embroidery, and am especially fascinated by Schiele and Klimt’s portraits, the way they are composed, and the poses of their subjects. They often depict women twisted or cramped into the frame, surrounded by elaborate patterns.

Recently, I have become fascinated with gestural contour portraits, which are made using a swift continuous line, never lifting the pencil off the page or even looking at it. Blind contour drawing gives me the freedom to let go and not worry about the outcome, which is a useful approach to life in general. I use blind contour drawing, especially fluid and gestural lines, and translate them into the more time-consuming art of sewing. In this way, the fabric pieces echo gesture drawings but are made in slow time, and hold onto feelings that are fleeting but impactful.

Certain fabrics featured in my work were given to me by my grandmother, and each holds a story. Some are remnants of clothing projects my great grandmother created for my grandmother to wear as a child. Others are upholstery fabric from furniture passed down through generations in my family.

The process of creating these portraits has been therapeutic as I work through personal pains, embrace scars, and consider how bodies can convey emotion without words. Our bodies are a record of our experiences, pain, battles, and torments.

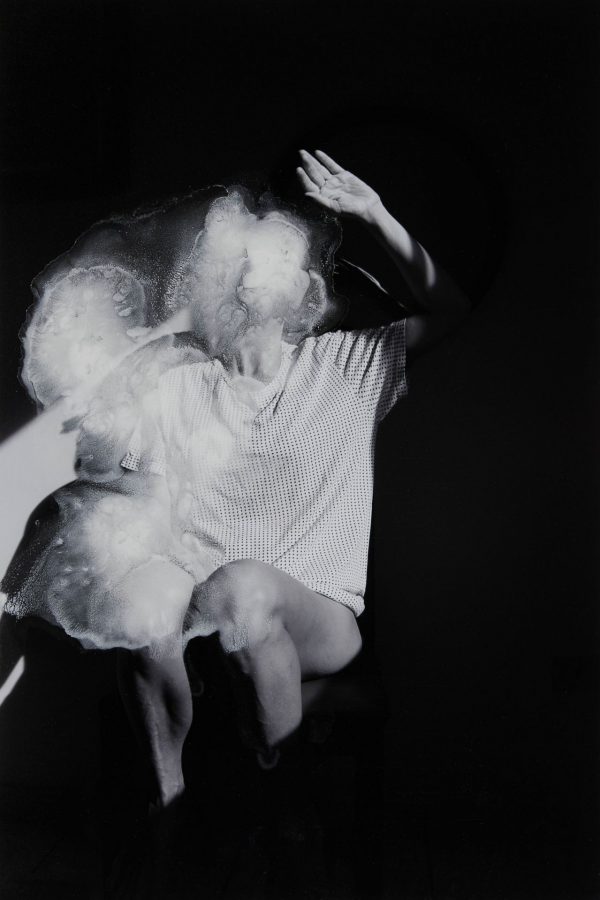

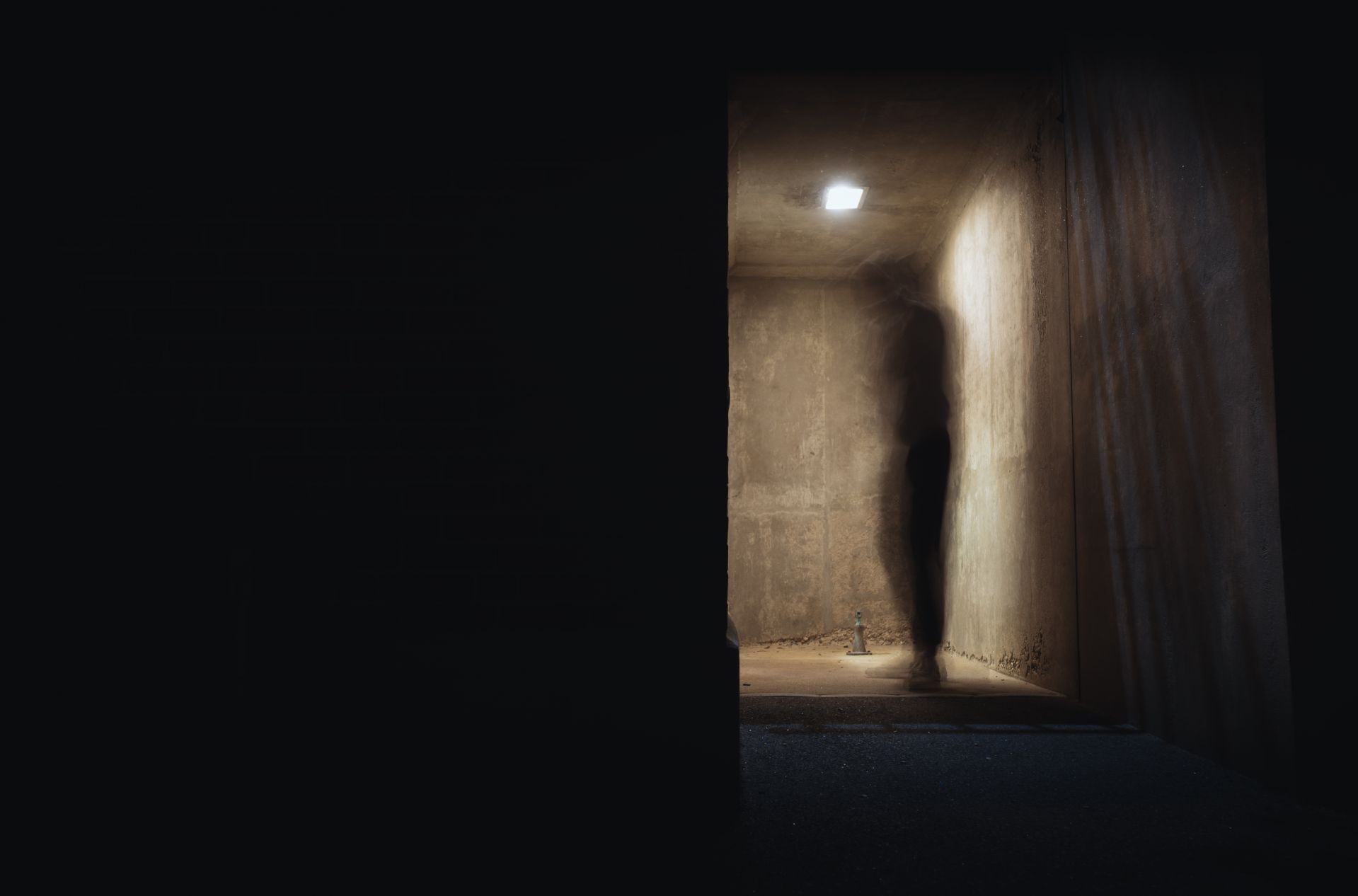

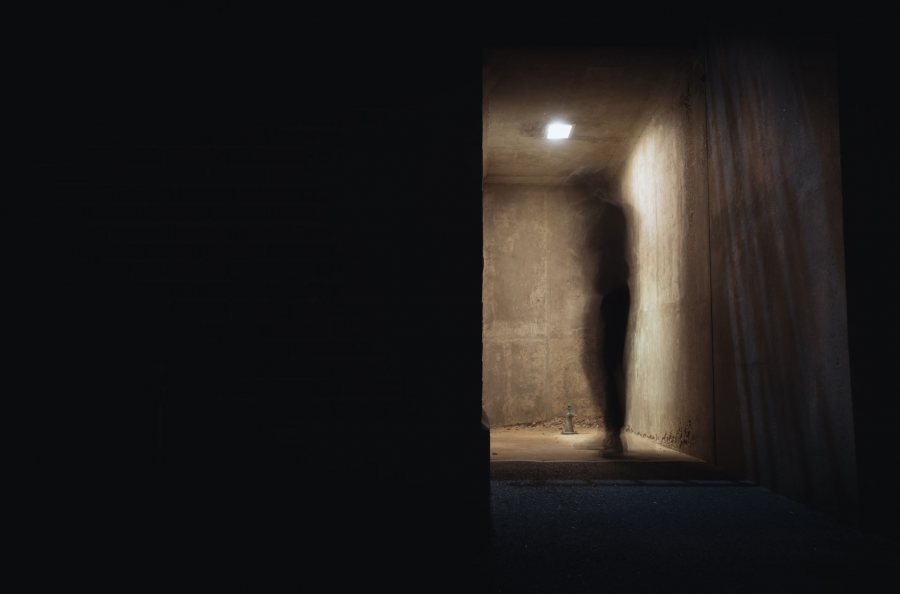

+Jeffrey Spellman

In this body of work, I utilize both photography and video. The group of portraits are all shot with shutter speeds slower than the typical speed associated with modern portraiture. Most portraiture today is captured with a fast shutter speed in an attempt to capture the most amount of detail with the least amount of blur. In contrast, the slow shutter speeds allow motion to be captured with both my own movement with the camera as well as the subject’s movement within the frame. The motion that appears in these portraits allows me to feel a deeper sense of emotion than typical portraiture. To me the subject in every image appears uncomfortable and distressed. This sense of discomfort is an important element throughout my body of work. Although I place the subject in an environment of my choosing it is ultimately their energy and emotion that dictates the tone of the image.

When photographing the subject, I ask them to move freely throughout the space. The subsequent unpredictability is what I enjoy most about the results. No two shots are ever the same and all of my preconceived ideas about what the shot will be are always incorrect. The difficulty is attempting to capture a noticeable amount of motion blur without completely obscuring the subject. It is not my goal to blur the subject beyond recognition. This means that a large portion of my time is spent experimenting with the length of exposure; too long the subject is unrecognizable, too short and the image becomes less evocative. My aim is to explore the space in between the familiar and blurred.

The work also includes a video that depicts the harsh realities of mass shootings. It serves as a chilling, instructional video describing what to do if you find yourself in a mass shooter situation. The video is purposefully devoid of human life other than the robotic voice present throughout the video. The video was inspired by the robotic response triggered by mass shootings in this country. The camera in this video serves as a character, and because of this the camera motion is perhaps the most important part of my process.

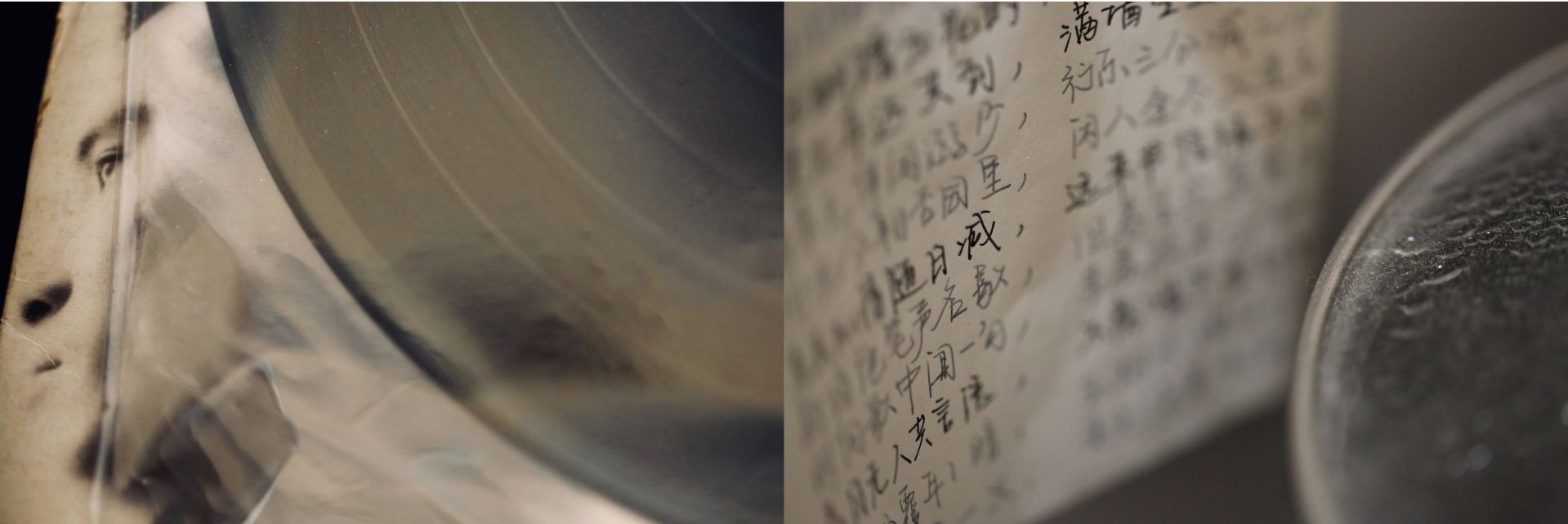

+Haiyao Tian

Objects tell stories of people, reveal their past and present, and speak to the inner world and individual experiences. My art is an exploration of personal narrative through objects.

I still vividly remember the day four years ago when I left home, with my life packed in two suitcases. I was so concerned about bringing my favorite books and pictures that I nearly forgot about more essential items such as medication. However, I never regret carrying so-called useless objects with me. It was these personal treasures I cherished that helped me to recreate a home away from home. I decorated my new room with incredible patience and a sheer tenderness, carefully arranging each item to ensure they would fit in well. Since then, I have spent countless days and nights in the wonderland I created for myself. My bond with this space is so strong that it is my sanctuary from the outside world, comforting me whenever I am frustrated or disorientated.

My art process involves attentive observation and fascinating repetition. I document my room day by day through digital photography, looking for beauty in the seemingly mundane.

I use wide-angle lenses, low points of view, limited frames, and shallow depth of field to create the sense of depth and ambiguity that I love in the work of Sally Mann and Todd Hido. I play with color a lot, referencing Williams Eggleston, the expert of color photography. I shoot from different angles, under different lighting conditions, and even with different background music. 70’s rock makes me feel energetic, while experimental music inspires me to include a sense of humor in my work. I want to push the boundaries of my imagination to make works that go beyond a simple documentation of personal objects, and instead are intimate, emotional, and meditative.

I set my heart on making diptychs to create harmonious yet exciting pieces by putting two images side by side. The pairings are partially based on similarities in composition, lighting, color, and geometric shapes, while also considering how well they blend in terms of content. I want the images to not only work in aesthetic ways but carry richer meanings when put side by side.

Ideally, every pair of images should be drastically different at first glance but match in nuanced ways. The juxtaposition of two images can be magical as if the two are having a dialogue with each other. And when many diptychs come together, they form a continuous narrative, a personal story, a private journal of being away from home, and a reflection on how objects carry one’s emotion, thoughts, memory, and identity. I have made a visual diary and to some extent, I would say this project is a personal portrait of myself.

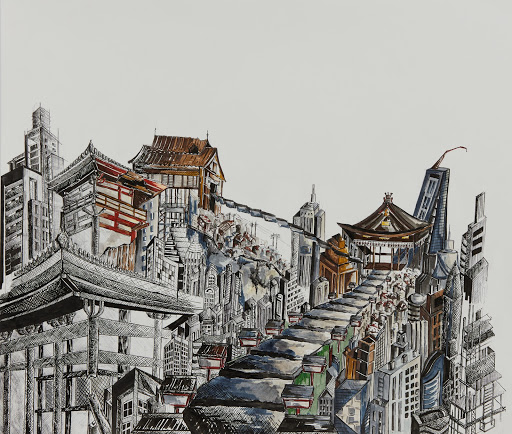

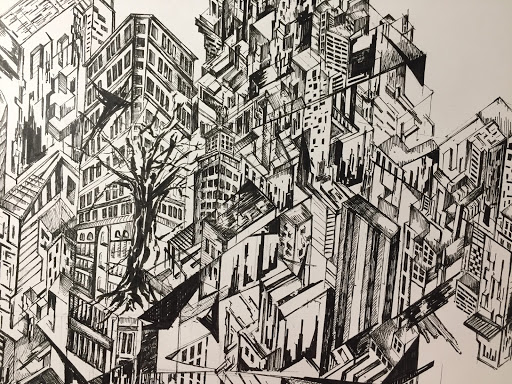

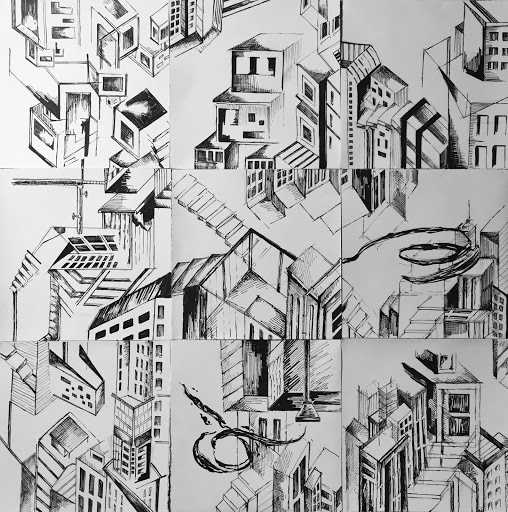

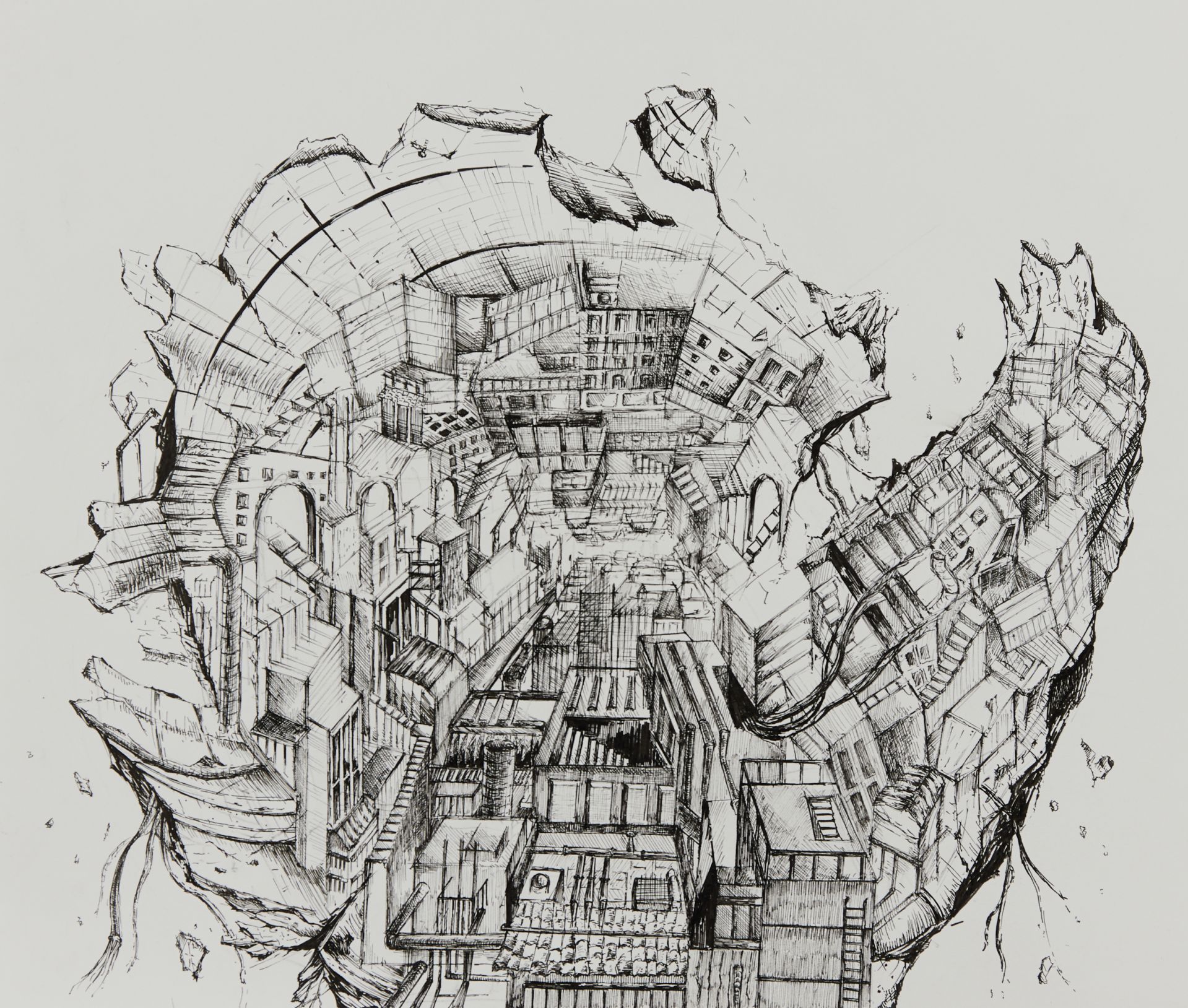

+Philip Wu

This body of work is my attempt to imagine a dystopian world by drawing different cityscapes. Growing up, I was instilled with the notion to not take the privileges I was given for granted, and I think about experiences and devastations I have been fortunate enough to avoid suffering. Our surroundings and the wider world reflect our actions and the consequences that follow, but few people choose to open their eyes and see what could and should be improved. I believe the landscape we live on today has the transformative potential to turn the world upside down and redefine the meaning of a happy ground. The concept of dystopia, meaning a bad place, crossed my mind as I thought about ways to investigate the pathway in which our reality has headed into. Using my interest in space and architecture, the approach I took to illustrate my perspective on dystopian cities is a twist reflecting possibilities that human actions can incur on the environment.

I work with pen and ink to create the drawings, and I applied color selectively to only a few of the pieces. By keeping the majority of my work monochromatic, I think each piece can transcend the boundaries of time. The series of work varies from detailed illustrations to abstraction, showing intersecting elements and structures that defy the norm and provoke confusion. While most of my work remains conceptual in nature, each work is conceived by integrating reflections of reality with fictional elements to construct a dystopian image. From my perspective, the theme of dystopia conjures up images of industries, machines, technologies, and the lost and constant renewal of history in an endless cycle. In one piece, temples that are conventionally viewed to have a spiritual connection to nature are surrounded by the mass constructed skyscrapers. The juxtaposition of modern and traditional structures constantly seen across this series was adopted to highlight the power dynamics in our environment. While drawing, I referred to photographs I took of cityscapes. My photos from different countries include slums, impoverished streets, nature, and skyscrapers. Sometimes, I abstract my illustrations by leaving the lines unconnected, to better evoke the fictional characteristic of dystopia.