Gardens, Goats, and Growth

This May, students in professor Christine Martinez’s Environmental Studies Short Term course saw the spring season through the lens of farmers and community gardeners. On the surface, their work was all about weeding, garden and food prep, and moving goats. As the students learned, though, the roots of the tasks they supported dug much deeper.

It was professor Martinez’s second time teaching “Local Food: Sovereignty and Justice” at Bates, which includes community-engaged learning in partnership with Gather to Grow (formerly known as St. Mary’s Nutrition Center), along with class visits to several other organizations including the Somali Bantu Community Association’s Liberation Farms and Presente! Maine. Professor Martinez leans into the opportunity Short Term presents to balance time in the classroom spent learning the research and scholarship of food justice and sovereignty, with time spent on experiential learning and solidarity work in downtown Lewiston, farms in Greene and Wales, and a fishway in Brunswick.

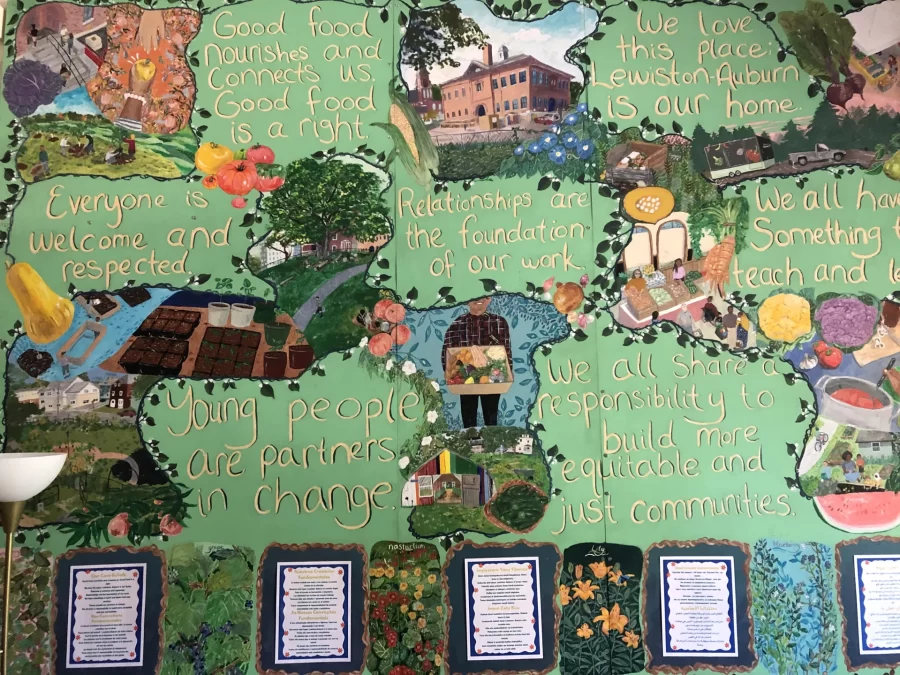

Students spent the largest amount of time working with a decades-old community partner with a brand new name. Recently establishing an independent 501(c)3 from St. Mary’s Health System, the former Nutrition Center has become Gather to Grow, with a mission of bringing “people together to collectively imagine and build a just food system and thriving community” (Gather to Grow, 2025). As evidence of how consistently professor Martinez can be found in the Gather to Grow community garden located behind the Harward Center on Wood Street, one can see her smiling face and fist full of beets on the front page of the Gather to Grow website. She models in her own community engagement the people and relationship-centered approach that her students also took away from the class.

Referencing the food pantry at Gather to Grow, one student reflected, “The volunteers and staff knew people’s names, what they liked, and their demeanor. A sense of consistency and care reminded me of what we discussed in class about relationship-centered food systems. These weren’t just people passing through a line, but they were neighbors. And the pantry wasn’t just about providing food but providing a space of care, stability, and even pride.” Similarly, another student emphasized how their perspective had been challenged: “I came into this class with some assumptions. I thought food justice work would be about charity, about giving to those in need. But I learned from the readings and on the ground that the most powerful food systems are built with communities, not for them.”

In addition to full class trips, students spent two hours each week volunteering on their own at either the community gardens or the food pantry, where they learned about both the consistency and flexibility required in building a just food system. As another student shared, “On my last visit to [Gather to Grow], I convinced some friends to join me. Although we weren’t able to garden due to torrential rain, we were invited into the kitchen, where Claudio put us to work chopping onions and garlic. On my 40th onion, I was reminded that when working in these kinds of positions—where we’re only completing one step in a larger process—it can be hard to see the end result and it can be easy to feel demotivated. Yet, when one of the women leading a course the following day saw that we had significantly cut her prep time, I was reminded that even when the result isn’t tangible, the contribution still holds value.”

This concept of being a small part of a much larger movement is one that we at the Harward Center strive to make clear to all community-engaged learners. For one student working on one small task within one class in one semester, it can be hard to grasp the meaning and impact of community-engaged work as a whole. For a bit of perspective on the larger picture, Bates has been partnering with Gather to Grow since its founding as the St. Mary’s Nutrition Center in 1999. Kristen Walter, Bates class of 2000, leads the organization as its founding executive director, and countless Bates students, faculty, and staff have worked alongside Kirsten and others to provide volunteer labor and to undertake mutually beneficial research and resource-development projects.

In similar fashion, professor Martinez’s students also spent time during Short Term moving goats (yes, you read that right!) at Liberation Farms in nearby Wales–an activity rooted in the long-time collaboration between professor emeritus of Anthropology Elizabeth Eames and the Somali Bantu Community Association headquartered in Lewiston. A new generation of Bates students found their work with Liberation farms a source of perspective change: “Working with goats was something completely new to me.” reflected one of Martinez’s students. “I’d never engaged with livestock before, and it opened my eyes to the scale and care involved in maintaining even a small herd. Goats are not just animals but also part of a sustainability, nutrition, and cultural heritage system for many of the farmers there. Livestock offered food and economic security, and it challenged my assumptions about what counts as a food system. It’s not just vegetables in neat rows, but land, labor, and livelihood all at once.” In addition to being a great learning opportunity, helping out with the baby goats infused a healthy dose of cuteness into the field experiences of the class.

Below the surface experiences of pulling bindweed, chopping onions, snuggling baby goats, and pulling up more bindweed, students’ critical reflections expose the deeper purpose of community-engaged learning: assumptions challenged, new sources of knowledge and expertise explored, and becoming a small part of a much larger ecosystem of community organizing and social change. Another participant reflects a final takeaway of community-engaged learning: “It wasn’t until this class that I actually felt like a part of the Lewiston community. Being able to meet people outside of Bates and contribute to the common good, I now feel much more grounded in my new home.”