Carl Sprinchorn and his Maine Odyssey

Many times, in my years at Bates thus far, I have thought to myself, “How did I end up in Lewiston, ME? I am not at all disparaging the school that I have called home for the past couple of years, a place I have grown fonder of with time, but I am genuinely interested in the paths which have led people from all over the country—and all over the world, in fact—to this picturesque, semi-urban campus in the northeastern corner of the U.S.

One could say the very same of Swedish-born American artist Carl Sprinchorn, a prolific artist who I have had the good fortune of exploring in my work as a Collections Management intern for the Bates Museum of Art. Born in 1887 in Broby, Sweden, Sprinchorn came to the U.S. in 1903, when he was just 15 years old, to study under renowned American artist Robert Henri at the New York School of Art, and later at the Henri Art School. Quickly establishing his roots in the New York art scene, Sprinchorn and his work found its way to smaller, group exhibitions and one-man shows in area galleries. Sprinchorn also formed influential friendships with avant-garde artists and patrons such as Florine, Carrie, and Ettie Stettheimer. While tied to New York through the tutelage of Henri, his early success in well-known galleries, and his notable patrons and collaborators, a new location and a new subject matter beckoned Sprinchorn: Maine.

In her article “Carl Sprinchorn, American Artist from Sweden,” Mary Towley Swanson explains how, when first coming to the Maine woods in 1919, Sprinchorn was drawn to a climate and landscape similar to his home country of Sweden, and also to a settlement in Monson, ME where a friend of his mother lived (and where Swedish was most likely still spoken). For two years afterward, Sprinchorn resided in the Maine North Woods, executing a number of landscape paintings and drawings of woodsmen, lumberjacks, and horse teams, documenting the life and work of the log drives. This was not Sprinchorn’s only sojourn in Maine, and he would return sporadically from 1937 through the summer of 1952, residing in the Patten/Shin Pond area, and forming lasting relationships with the farmers and woodsmen who inspired his work.

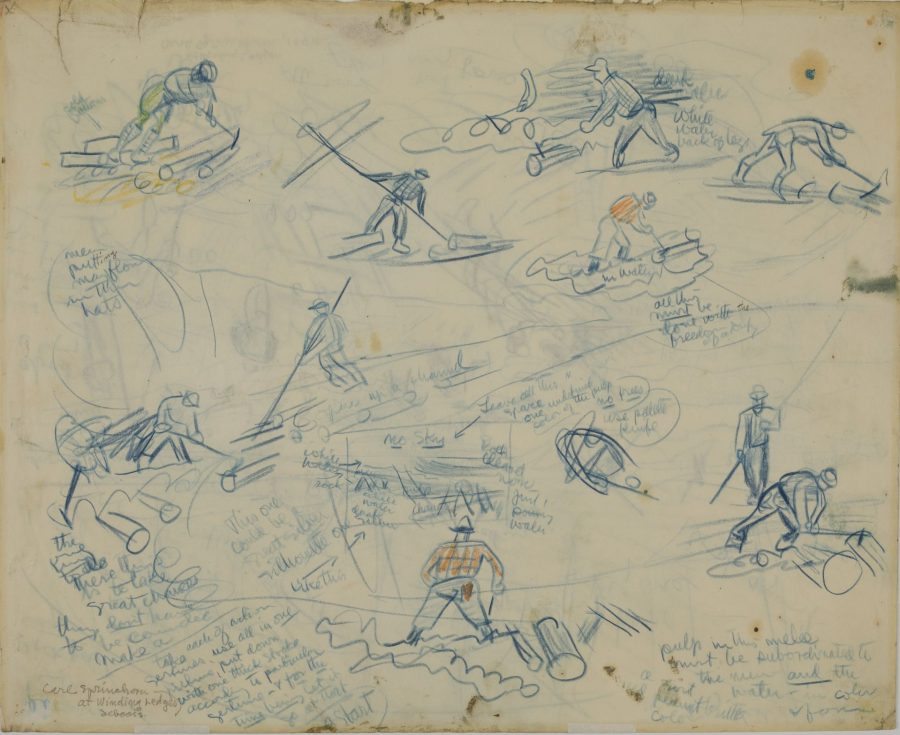

Maine’s natural beauty and its similarity to his Swedish homeland can partially explain Sprinchorn’s journeys up north, but why the seeming obsession with the workingmen of the forest? Perhaps Sprinchorn can explain it best. In his unsuccessful application for a Guggenheim fellowship in 1942, Sprinchorn wrote about his future plans: “The continuation of my recent, purely creative work in the Penobscot River country of Maine, interpreting the way of life of the woodsman who, as lumberjack, trapper, or hunter continues today his traditional, heroic and picturesque labors, without having been tendered the homage, through the art of painting, that he humanly and historically deserves.” It seems that in the woodsmen, Sprinchorn saw much more than the tedium of manual labor, he saw the universal. As a close friend and confidant of Sprinchorn’s, Henry W. Wells, described for The American Scandinavian Review, many of Sprinchorn’s works were concerned with subject matter quintessentially realist (i.e. lumberjacks, horses, forested landscapes), yet rendered in a manner which eschewed Realism, instead celebrating the act of painting itself.

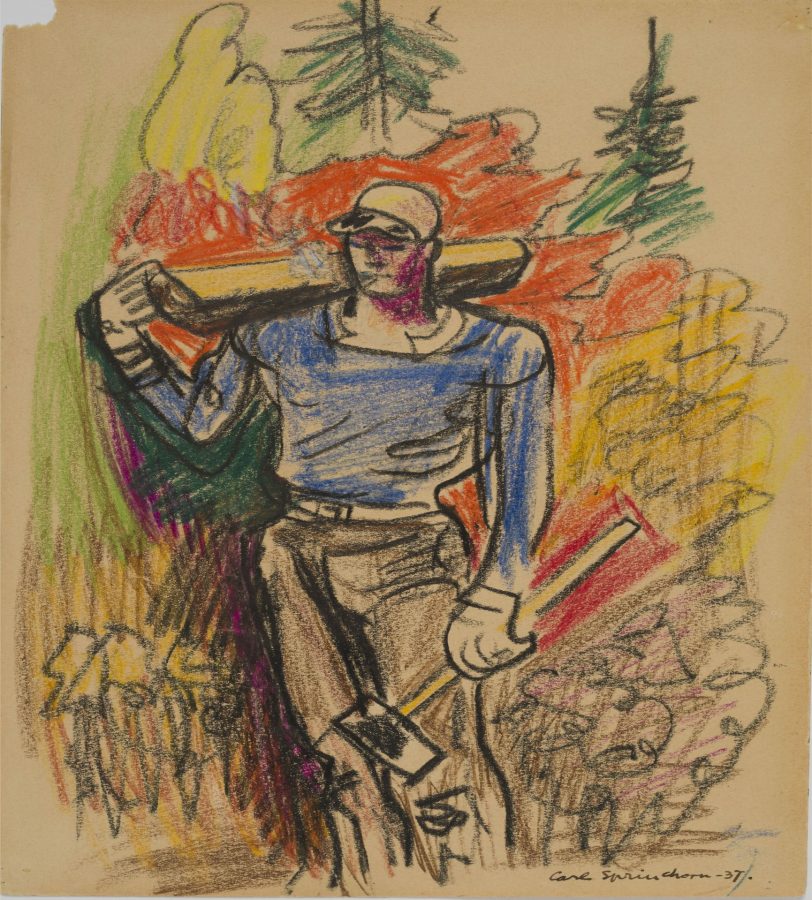

Looking at two of Sprinchorn’s drawings in the Museum’s collection—part of an extensive gift of over one hundred works donated by the Carl Sprinchorn Admiration Society in 2018—one can see how Sprinchorn’s appreciation of the meditative nature of the Maine woods and his exploration of universal themes overlap. In his crayon drawing One of the Getchell Boys, Shin Pond Maine from 1937, Sprinchorn depicts a lumberjack paused in the midst of his work, seemingly unaware of our presence. A log slung over his shoulder and an axe grasped in his other hand, this worker of the woods gazes at a scene that we cannot see. This figure is contrasted by a colorful, sylvan background which epitomizes Sprinchorn’s habit of juxtaposing the subject matter of the everyday with a technique increasingly abstract.

Similarly, in another crayon drawing from the same year titled Lumbermen Playing Cards, Sprinchorn illustrates a commonplace logging-camp scene, but with connotations which stretch beyond. Much like the previous drawing, Lumbermen Playing Cards is the manifestation of Sprinchorn’s experiences and observations living amongst woodsmen, lumberjacks, and teamsters alike in the deep woods of Maine. He is privy to this intimate, social, and—one could even say, mundane—scene of lumbermen enjoying one another’s company because he knows them personally. However, one also gets the sense that this scene signals more, perhaps also serving as a consideration of the human tendency to come together, even in the most remote places and with the most solitary-minded people.

Perhaps I am overanalyzing this but it is nonetheless inarguable that Sprinchorn found a poetic beauty in the wooded landscapes of Maine and the people who lived there. Sprinchorn is often examined and talked about in conjunction with his close friend, and Lewiston, Maine native, Marsden Hartley. As Swanson accounts in her article, Hartley penned four different essays about Sprinchorn’s works, and he argued that (in conjunction with Sprinchorn), “together we have given a reasonable account of the qualities of Maine.”

Between Hartley’s prized landscapes and figure drawings and Sprinchorn’s extensive oeuvre, I very much agree with this statement. While the Bates Museum of Art is known for its vast collection of artworks and belongings of the more well-known Hartley, and while their friendship is certainly important to consider in terms of their influencing one another, I think it is time for Sprinchorn to gain new appreciation here in Lewiston, ME.

And while my time as an intern with the Bates Museum has been punctuated by a modicum of tasks that one could deem boring and tedious, examining and cataloguing Sprinchorn’s works, researching his life and what others have said about him, have taught me to the appreciate the beauty of the mundane and the value of doing the little things right.

A special thank you to the friend I never met and never knew I needed—I appreciate you Carl.

Bridget Thompson ‘22

Art & Visual Culture and History Major

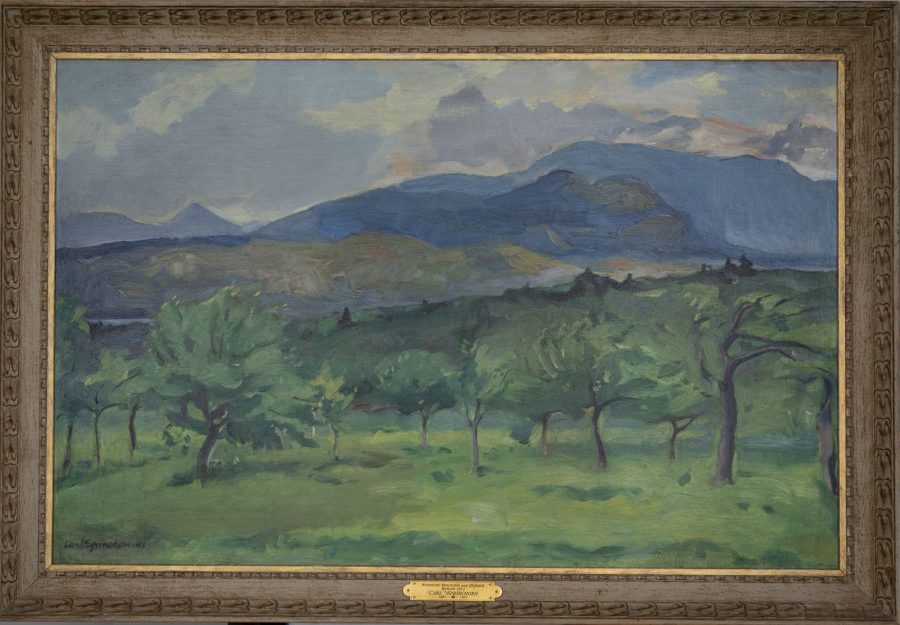

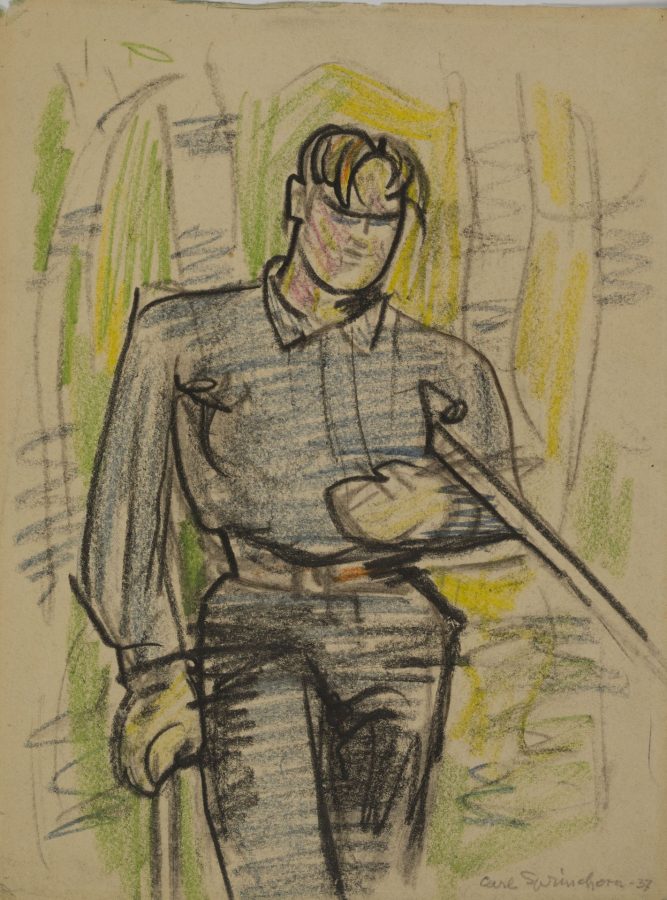

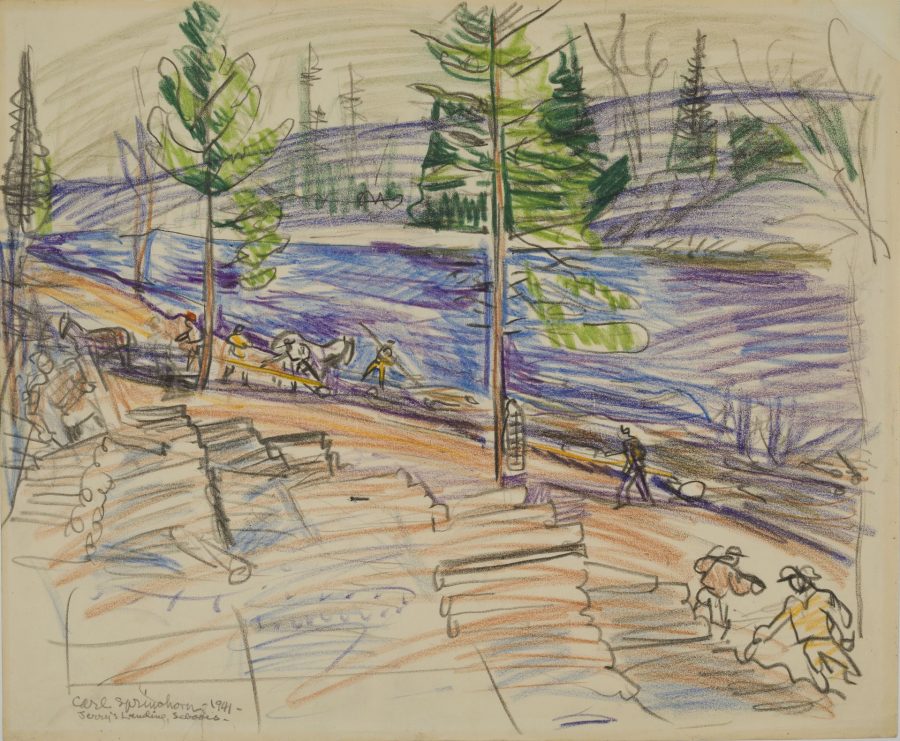

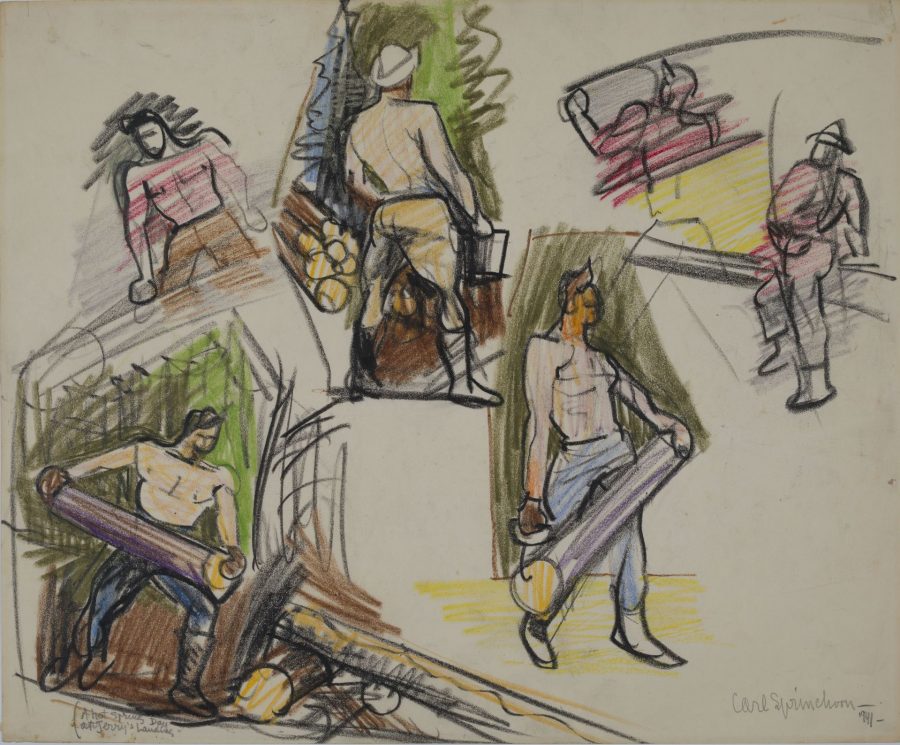

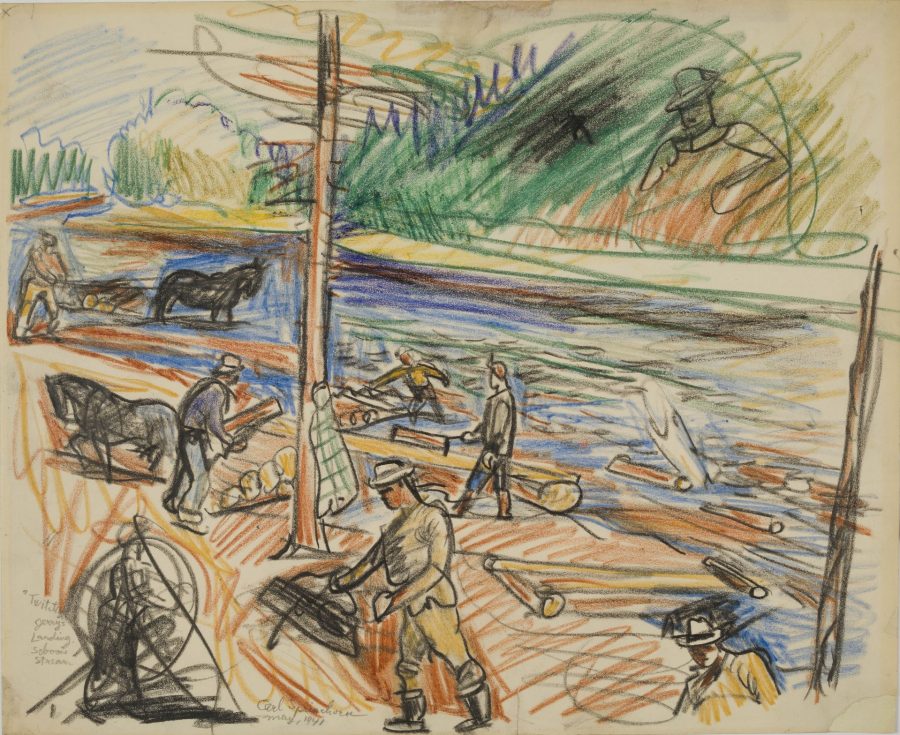

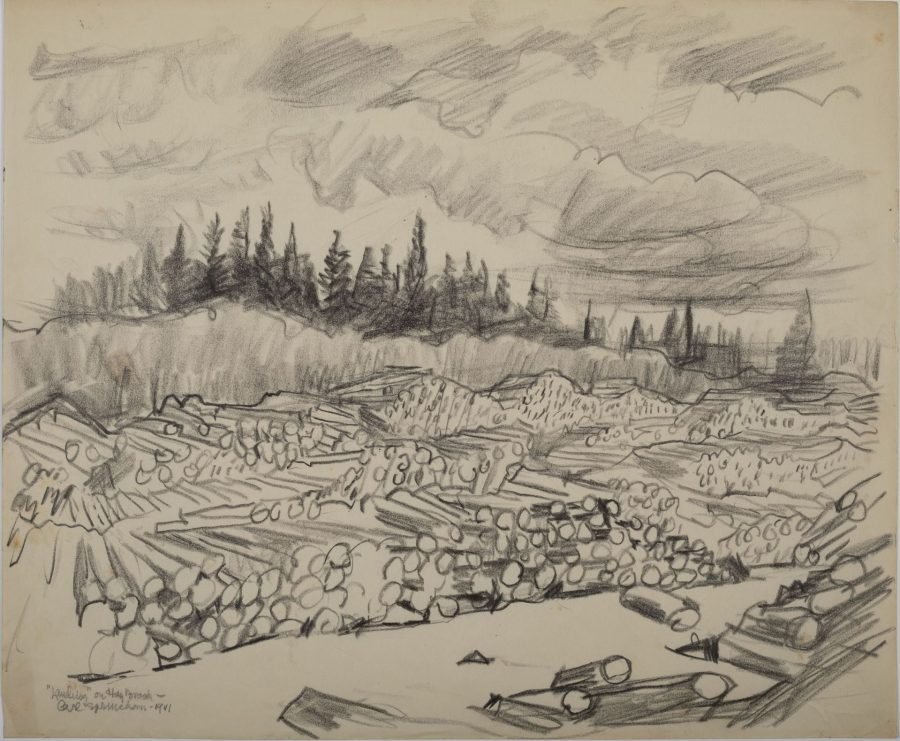

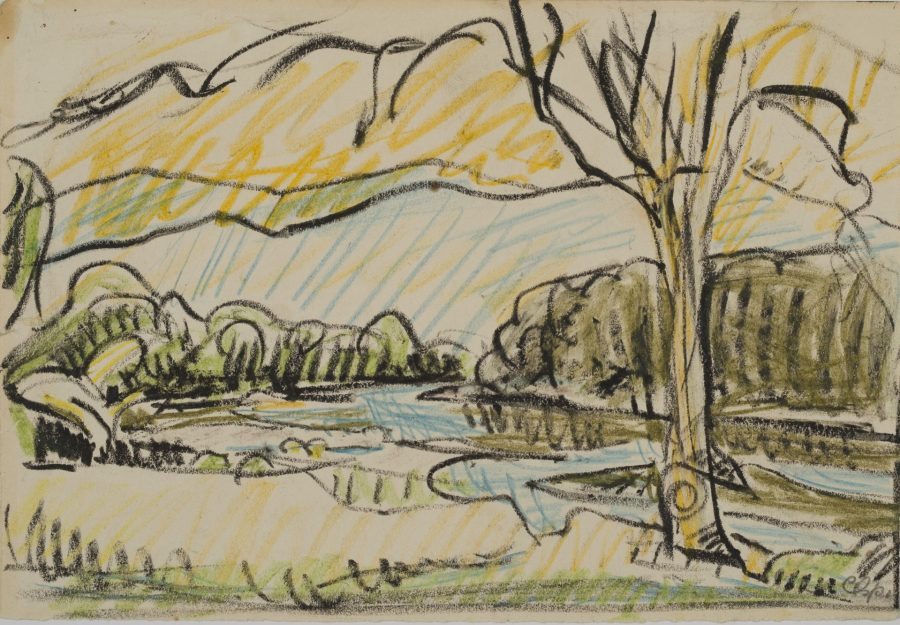

Below are a selection of images from a recent gift by the Carl Sprinchorn Admiration Society. All works by Carl Sprinchorn.

Borestone Mountain and Orchard, Monson (Distant Rain), 1911, oil on canvas mounted on masonite, 2018.5.86

Self-Portrait on hotel stationery, 1924, graphite on paper, 2018.5.2

Winter Horse Team, Crommett Farm, 1937, crayon on paper, 2018.5.9

One of the Getchell Boys, Shin Pond, 1937, crayon and charcoal on paper, 2018.5.42

Teamster, Crommett Farm, 1937, colored pencil and ink on paper, 2018.5.47

At Winding Ledges, Seboeis – Pulp within the Melee, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.29a

Sheep Tail, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.32

Jerry’s Landing, Seboies, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.38

A Hot Spring Day at Jerry’s Landing, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.36

Twitchers at Jerry’s Landing, May 10-14, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.37

Twitching, Jerry’s Landing – Seboies, May 10-14, 1941, crayon on paper, 2018.5.39

Yarded Pulp, 1941, pastel on gray paper,2018.5.52

Landing on the Brook, 1941, charcoal on paper, 2018.5.96

East Branch Penobscot, 1944, crayon on paper, 2018.5.60

North Star over Nat’s Camp, Hunt Farm, East Branch of the Penobscot River, December, 1944, watercolor on toned paper, 2018.5.58