Pollution, Sea Turtles, and Fish

BIO 209

Student Blog Series

Garbage and Sea Turtles

Charlotte Cabot

Sea turtles are currently a threatened species and recently trash and debris that wash up on shore are imposing greater challenges for sea turtle hatchlings to make a successful journey to the ocean’s waters. The study “Beach Condition and Marine Debris: New Hurdles for Sea Turtle Hatchling Survival” was conducted from mid-July to mid-September in 2004 on Fethiye Beach, Southwest Turkey. This study examined the effects of marine debris as barriers on the loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta (L.). Researchers used five items that are frequently accumulated on beaches to see if debris blocked the sea turtles from reaching the ocean. They were: empty plastic bottles, styrofoam cups, plastic canisters, heap nets, and single layer nets. Each item was tested individually of the other items and was positioned three meters away from the nest in rows. The study claimed that the spacing and numbering of the elements were chosen to maximize the encounter rate but not be unavoidable. Results showed that the canister, the heap net, and the single layer nets lead to a majority of unsuccessful attempts of the sea turtles. The trial was deemed unsuccessful if the hatchling was entrapped for ten minutes. This result shows that the debris can have a substantial negative effect on the sea turtle hatchlings. In addition to beach debris a whole host of factors threaten the sea turtle such as entanglement, toxins, ingestion of plastic, natural predators, and light pollution. All of these things could lead to the continued decline of sea turtles which would have a negative impact on the surrounding species and ecosystems, because the loss of one species in a close-knit ecosystem would not go unnoticed. The article acknowledges that one thing that everyone can do to help the livelihood of sea turtles in the future is to participate in coastal cleanups. This article illustrates that debris blocking sea turtle hatchlings from reaching the ocean is a problem that can be fixed and therefore should inspire everyone to keep our beaches clean!

Oil Spills and Predatory Fish

Isobel Curtis

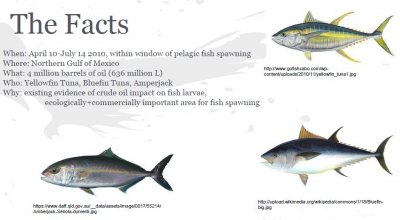

Many of us are familiar with the disturbing images of wildlife coated in oil that flood the media following oil spills. However, few are aware of the impact this oil has below the surface. In addition to huge visible oil slicks, crude oil contains thousands of chemical compounds that can harm wildlife. This study examined the effect of crude oil-derived polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), known to directly disrupt fish cardiac function, on three types of pelagic fish larvae found in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 released 4 million barrels of crude oil into the gulf. Oil released from wells on the ocean floor rose to the surface where it came into contact with floating fish larvae. The spill coincided with spawning times for all three species studied. Bluefin tuna, Yellowfin tuna and Amperjack larvae were grown in laboratory environments mimicking the PAH concentrations of seawater samples taken shortly after the oil spill.

All three fish species that were studied (Yellowfin Tuna, Bluefin Tuna, Amperjack) exhibited identical morphological defects. Failure of the circulatory system caused pericardial fluid to accumulate, called edema, and distorted the shape of the yolk mass. Reduced eye growth, abnormal fin development and abnormal curvature of the body were also noted in all species. Cardiovascular defects included slower heart rate (bradycardia), prolonged systolic phase (arrhythmia), and increased beat-to-beat variability (heartbeat irregularity). All species exhibited cardiotoxicity at PAH exposures less than 15ug/L. However, threshold concentrations for arrhythmia were very low (1ug/L) for amberjack and yellowfin tuna. Additionally, 50% of tuna embryos exhibited edema at 2-3 ug/L. 30% and 20% of water samples collected following the spill had PAH concentrations higher than threshold values for arrhythmia and edema, respectively. Larvae with severe edema have high mortality, indicating larvae spawned in areas with just a few micrograms of PAHs (highest concentration was 84ug/L) may not have survived to adulthood. These results support previous studies of the effect of PAHs on zebra fish, herring and salmon and indicate sensitivity to PAHs over a broad range of fish species and habitats.