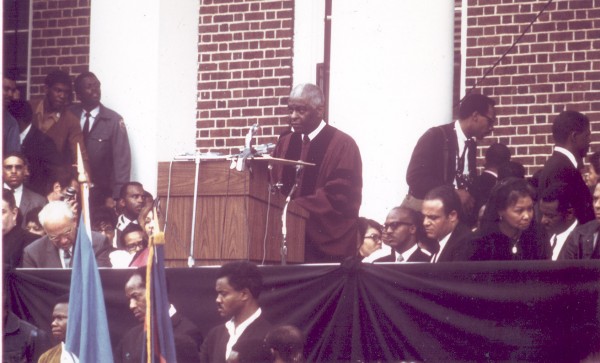

April 1968: Benjamin Mays ’20 delivers final eulogy for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Benjamin Mays ’20 and the Rev. Martin Luther King promised each other: He who outlived the other would deliver his friend’s last eulogy. On April 9, 1968, Mays made good on the promise.

After funeral services at Ebenezer Baptist Church, King’s mahogany coffin was born to Morehouse College on a rickety farm wagon pulled by two mules.

There, Mays, the school’s 70-year-old president emeritus, delivered a final eulogy that also renounced what many saw coming: a turn toward violence for the black movement.

King was “more courageous than those who advocate violence as a way out,” Mays told the estimated 150,000 mourners. “Martin Luther faced the dogs, the police, jail, heavy criticism, and finally death; and he never carried a gun, not even a knife to defend himself. He had only his faith in a just God to rely on.”

Indeed, King’s assassination by James Earl Ray left many questioning the future of nonviolent protest in the late 1960s. Quoted in Time magazine a week after King’s funeral, Floyd McKissick, chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, offered this sober judgment: “The way things are today, not even Christ could come back and preach nonviolence.”

Benjamin Mays, Class of 1920, eulogy for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

To be honored by being requested to give the eulogy at the funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is like asking one to eulogize his deceased son — so close and so precious was he to me. Our friendship goes back to his student days at Morehouse. It is not an easy task; nevertheless I accept it, with a sad heart and with full knowledge of my inadequacy to do justice to this man. It was my desire that if I predeceased Dr. King, he would pay tribute to me on my final day. It was his wish that if he predeceased me, I would deliver the homily at his funeral. Fate has decreed that I eulogize him. I wish it might have been otherwise; for, after all I am three score years and 10 and Martin Luther is dead at 39.

Although there are some who rejoice in his death, there are millions across the length and breadth of this world who are smitten with grief that this friend of mankind — all mankind — has been cut down in the flower of his youth. So, multitudes here and in foreign lands, queens, kings, heads of governments, the clergy of the world, and the common man everywhere, are praying that God will be with the family, the American people, and the president of the United States in this tragic hour. We hope that this universal concern will bring comfort to the family — for grief is like a heavy load: when shared it is easier to bear. We come today to help the family carry the load.

He was convinced that people could not be moved to abolish voluntarily the inhumanity of man to man by mere persuasion and pleading.

We have assembled here from every section of this great nation and from other parts of the world to give thanks to God that He gave to America, at this moment in history, Martin Luther King Jr. Truly God is no respecter of persons. How strange! God called the grandson of a slave on his father’s side, and the grandson of a man born during the Civil War on his mother’s side, and said to him: Martin Luther, speak to America about war and peace; about social justice and racial discrimination; about its obligation to the poor; and about nonviolence as a way of perfecting social change in a world of brutality and war.

Here was a man who believed with all of his might that the pursuit of violence at any time is ethically and morally wrong; that God and the moral weight of the universe are against it; that violence is self-defeating; and that only love and forgiveness can break the vicious circle of revenge. He believed that nonviolence would prove effective in the abolition of injustice in politics, in economics, in education, and in race relations. He was convinced, also, that people could not be moved to abolish voluntarily the inhumanity of man to man by mere persuasion and pleading, but that they could be moved to do so by dramatizing the evil through massive nonviolent resistance. He believed that nonviolent direct action was necessary to supplement the nonviolent victories won in federal courts. He believed that the nonviolent approach to solving social problems would ultimately prove to be redemptive.

He gave people an ethical and moral way to engage in activities designed to perfect social change without bloodshed and violence.

Out of this conviction, history records the marches in Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, Chicago and other cities. He gave people an ethical and moral way to engage in activities designed to perfect social change without bloodshed and violence; and when violence did erupt it was that which is potential in any protest which aims to uproot deeply entrenched wrongs. No reasonable person would deny that the activities and the personality of Martin Luther King Jr. contributed largely to the success of the student sit-in movements in abolishing segregation in downtown establishments; and that his activities contributed mightily to the passage of the Civil Rights legislation of 1964 and 1965.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed in a united America. He believed that the walls of separation brought on by legal and de facto segregation, and discrimination based on race and color, could be eradicated. As he said in his Washington Monument address: “I have a dream.”

As he and his followers so often sang: “We shall overcome someday; black and white together.”

He had faith in his country. He died striving to desegregate and integrate America to the end that this great nation of ours, born in revolution and blood, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created free and equal, will truly become the lighthouse of freedom where none will be denied because his skin is black and none favored because his eyes are blue; where our nation will be militarily strong but perpetually at peace; economically secure but just; learned but wise; where the poorest — the garbage collectors — will have bread enough and to spare; where no one will be poorly housed; each educated up to his capacity; and where the richest will understand the meaning of empathy. This was his dream, and the end toward which he strove. As he and his followers so often sang: “We shall overcome someday; black and white together.”

Let it be thoroughly understood that our deceased brother did not embrace nonviolence out of fear or cowardice. Moral courage was one of his noblest virtues. As Mahatma Gandhi challenged the British Empire without a sword and won, Martin Luther King Jr. challenged the interracial wrongs of his country without a gun. And he had the faith to believe that he would win the battle for social justice. I make bold to assert that it took more courage for King to practice nonviolence than it took his assassin to fire the fatal shot. The assassin is a coward: He committed his dastardly deed and fled. When Martin Luther disobeyed an unjust law, he accepted the consequences of his actions. He never ran away and he never begged for mercy. He returned to the Birmingham jail to serve his time.

He had only his faith in a just God to rely on; and the belief that “thrice is he armed who has his quarrels just.”

Perhaps he was more courageous than soldiers who fight and die on the battlefield. There is an element of compulsion in their dying. But when Martin Luther faced death again and again, and finally embraced it, there was no external pressure. He was acting on an inner compulsion that drove him on. More courageous than those who advocate violence as a way out, for they carry weapons of destruction for defense. But Martin Luther faced the dogs, the police, jail, heavy criticism, and finally death; and he never carried a gun, not even a knife to defend himself. He had only his faith in a just God to rely on; and the belief that “thrice is he armed who has his quarrels just.” The faith that Browning writes about when he says:

“One who never turned his back but marched breast forward, / Never doubted clouds would break, / Never dreamed, though right were worsted, wrong would triumph, / Held we fall to rise, and baffled to fight better, / Sleep to wake.”

Coupled with moral courage was Martin Luther King Jr.’s capacity to love people. Though deeply committed to a program of freedom for Negroes, he had love and concern for all kinds of peoples.

He would probably say that if death had to come, I am sure there was no greater cause to die for than fighting to get a just wage for garbage collectors.

He drew no distinction between the high and low; none between the rich and the poor. He believed especially that he was sent to champion the cause of the man farthest down. He would probably say that if death had to come, I am sure there was no greater cause to die for than fighting to get a just wage for garbage collectors. He was supra-race, supra-nation, supra-denomination, supra-class and supra-culture. He belonged to the world and to mankind. Now he belongs to posterity.

But there is a dichotomy in all this. This man was loved by some and hated by others. If any man knew the meaning of suffering, King knew. House bombed; living day by day for 13 years under constant threats of death; maliciously accused of being a Communist; falsely accused of being insincere and seeking limelight for his own glory; stabbed by a member of his own race; slugged in a hotel lobby; jailed 30 times; occasionally deeply hurt because his friends betrayed him — and yet this man had no bitterness in his heart, no rancor in his soul, no revenge in his mind; and he went up and down the length and breadth of this world preaching nonviolence and the redemptive power of love. He believed with all of his heart, mind and soul that the way to peace and brotherhood is through nonviolence, love and suffering.

He was severely criticized for his opposition to the war in Vietnam. It must be said, however, that one could hardly expect a prophet of Dr. King’s commitments to advocate nonviolence at home and violence in Vietnam. Nonviolence to King was total commitment not only in solving the problems of race in the United States, but the problems of the world.

No! He was not ahead of his time. No man is ahead of his time. Every man is within his star, each in his time.

Surely this man was called of God to do this work. If Amos and Micah were prophets in the eighth century B.C., Martin Luther King Jr. was a prophet in the 20th century. If Isaiah was called of God to prophesy in his day, Martin Luther was called of God to prophesy in his time. If Hosea was sent to preach love and forgiveness centuries ago, Martin Luther was sent to expound the doctrine of nonviolence and forgiveness in the third quarter of the 20th century. If Jesus was called to preach the Gospel to the poor, Martin Luther was called to give dignity to the common man. If a prophet is one who interprets in clear and intelligible language the will of God, Martin Luther King Jr. fits that designation. If a prophet is one who does not seek popular causes to espouse, but rather the causes he thinks are right, Martin Luther qualified on that score.

No! He was not ahead of his time. No man is ahead of his time. Every man is within his star, each in his time. Each man must respond to the call of God in his lifetime and not in somebody else’s time. Jesus had to respond to the call of God in the first century A.D., and not in the 20th century. He had but one life to live. He couldn’t wait. How long do you think Jesus would have had to wait for the constituted authorities to accept him? Twenty-five years? A hundred years? A thousand? He died at 33. He couldn’t wait. Paul, Galileo, Copernicus, Martin Luther the Protestant reformer, Gandhi and Nehru couldn’t wait for another time. They had to act in their lifetimes. No man is ahead of his time. Abraham, leaving his country in the obedience to God’s call; Moses leading a rebellious people to the Promised Land; Jesus dying on a cross, Galileo on his knees recanting; Lincoln dying of an assassin’s bullet; Woodrow Wilson crusading for a League of Nations; Martin Luther King Jr. dying fighting for justice for garbage collectors — none of these men were ahead of their time. With them the time was always ripe to do that which was right and that which needed to be done.

Too bad, you say, that Martin Luther King Jr. died so young. I feel that way, too. But, as I have said many times before, it isn’t how long one lives, but how well. It’s what one accomplishes for mankind that matters. Jesus died at 33; Joan of Arc at 19; Byron and Burns at 36; Keats at 25; Marlow at 29; Shelley at 30; Dunbar before 35; John Fitzgerald Kennedy at 46; William Rainey Harper at 49; and Martin Luther King Jr. at 39.

We all pray that the assassin will be apprehended and brought to justice. But, make no mistake, the American people are in part responsible for Martin Luther King Jr.’s death. The assassin heard enough condemnation of King and of Negroes to feel that he had public support. He knew that millions hated King.

We, and not the assassin, represent America at its best. We have the power — not the prejudiced, not the assassin — to make things right.

The Memphis officials must bear some of the guilt for Martin Luther’s assassination. The strike should have been settled several weeks ago. The lowest paid men in our society should not have to strike for a more just wage. A century after Emancipation, and after the enactment of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, it should not have been necessary for Martin Luther King Jr. to stage marches in Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma, and go to jail 30 times trying to achieve for his people those rights which people of lighter hue get by virtue of their being born white. We, too, are guilty of murder. It is time for the American people to repent and make democracy equally applicable to all Americans. What can we do? We, and not the assassin, represent America at its best. We have the power — not the prejudiced, not the assassin — to make things right.

If we love Martin Luther King Jr., and respect him, as this crowd surely testifies, let us see to it that he did not die in vain; let us see to it that we do not dishonor his name by trying to solve our problems through rioting in the streets.

Violence was foreign to his nature. He warned that continued riots could produce a fascist state. But let us see to it also that the conditions that cause riots are promptly removed, as the president of the United States is trying to get us to do so. Let black and white alike search their hearts; and if there be prejudice in our hearts against any racial or ethnic group, let us exterminate it and let us pray, as Martin Luther King Jr. would pray if he could: “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” If we do this, Martin Luther King Jr. will have died a redemptive death from which all mankind will benefit….

I close by saying to you what Martin Luther King Jr. believed: If physical death was the price he had to pay to rid America of prejudice and injustice, nothing could be more redemptive. And, to paraphrase the words of the immortal John Fitzgerald Kennedy, permit me to say that Martin Luther King Jr.’s unfinished work on earth must truly be our own.

From Born to Rebel: An Autobiography by Benjamin E. Mays. Copyright 1971 by Benjamin E. Mays. Used by permission of the University of Georgia Press.