2025 Barlow Travel Grant

Ed Zuis ’88

Personal Background

My high school Chemistry and Physics teacher was the kind of person who cared about students and had so much fun teaching. It was contagious. He inspired me to attend college with the goal of becoming a high school physics teacher. My Bates College experience prepared me to do exactly that.

The Bates College Physics Department was a group of incredibly intelligent people who seemed to enjoy science education as much as my high school teacher did. The Education Department’s community field experiences were priceless. I will never forget a third grader asking me, a college sophomore, “Mr. Zuis, can I go to the bathroom?” I froze! This youngster was calling me “Mr. Zuis” and I did not know any of the rules about letting an 8-year-old out of the classroom. But after four years at Bates, I was prepared to teach.

Throughout my teaching career, I have looked for opportunities for continued improvement. These included obtaining a Master’s degree, presenting at national conferences, hosting student teachers, and a stint as Bates College’s first “Teacher in Residence”. These pursuits were mostly about being a good educator and not specifically about science.

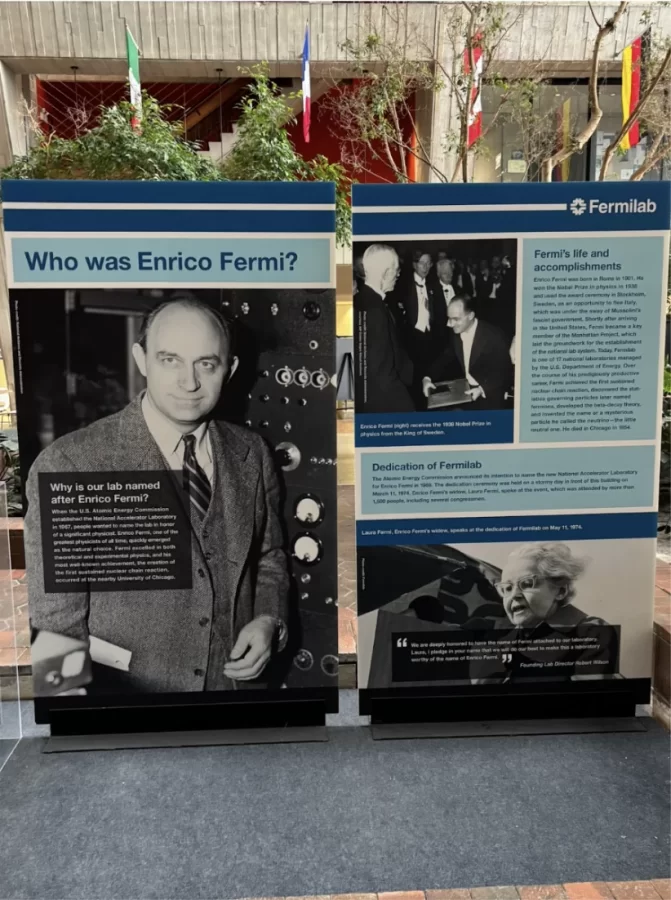

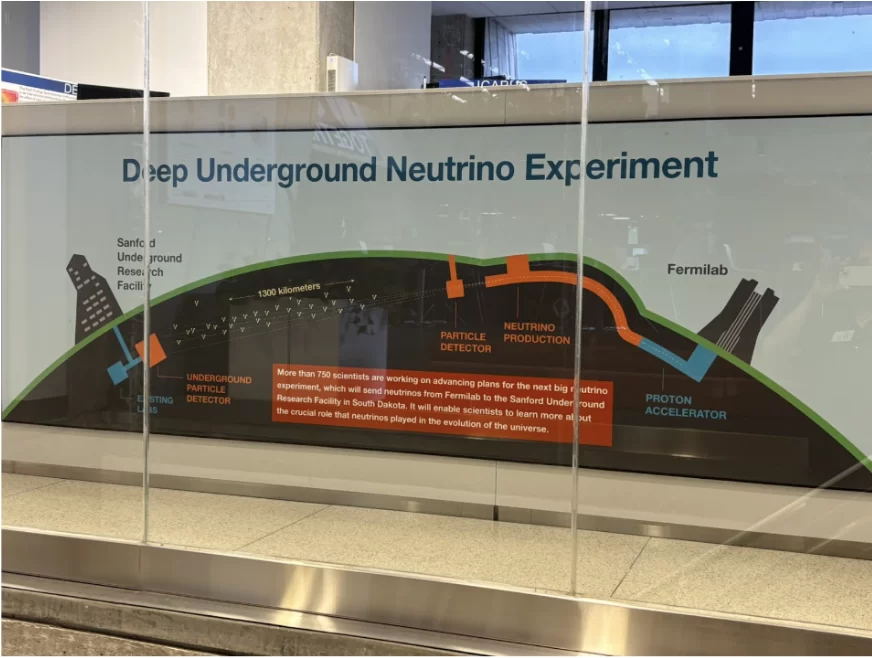

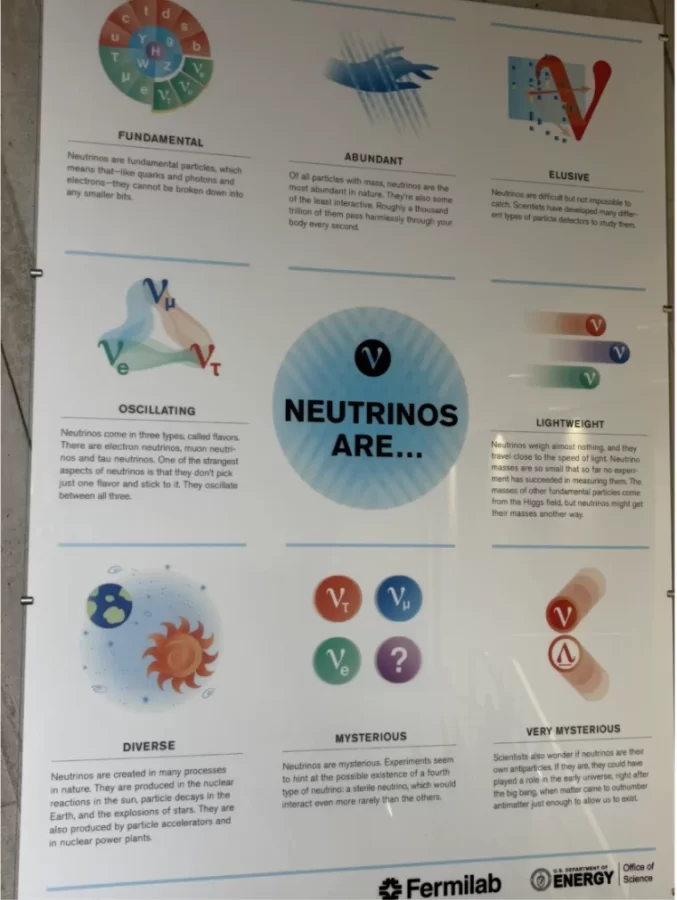

The world of particle physics is constantly changing and enhancing our understanding of so many other scientific concepts. These include the Big Bang Theory, Quantum Theory, and Dark Matter. World-changing advancements in physics are happening at Fermilab (near Chicago) and CERN (Geneva, Switzerland).

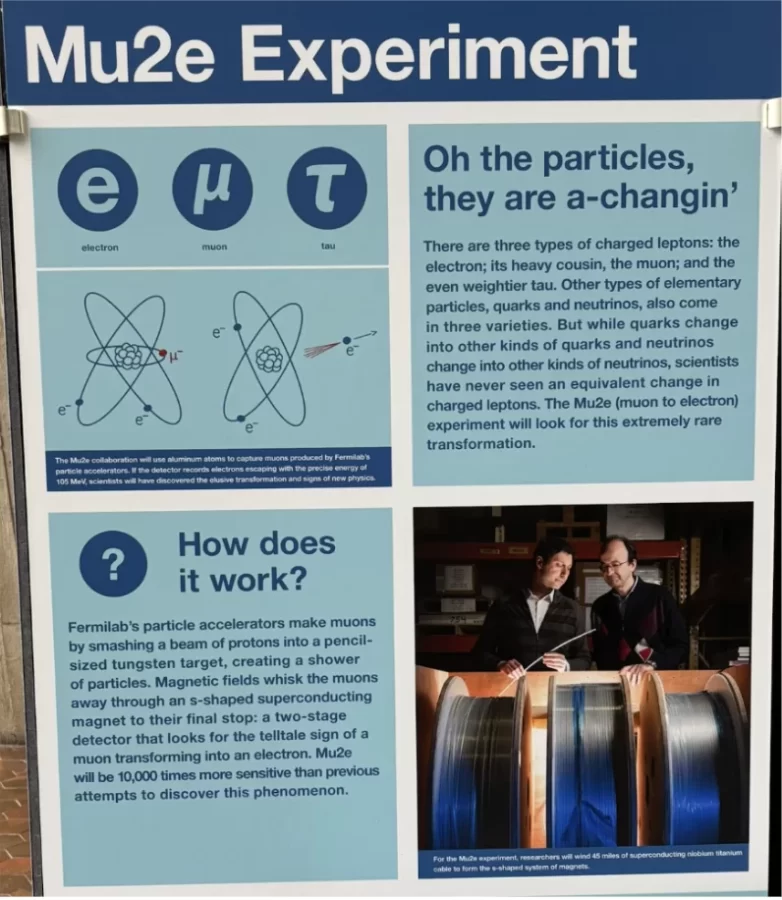

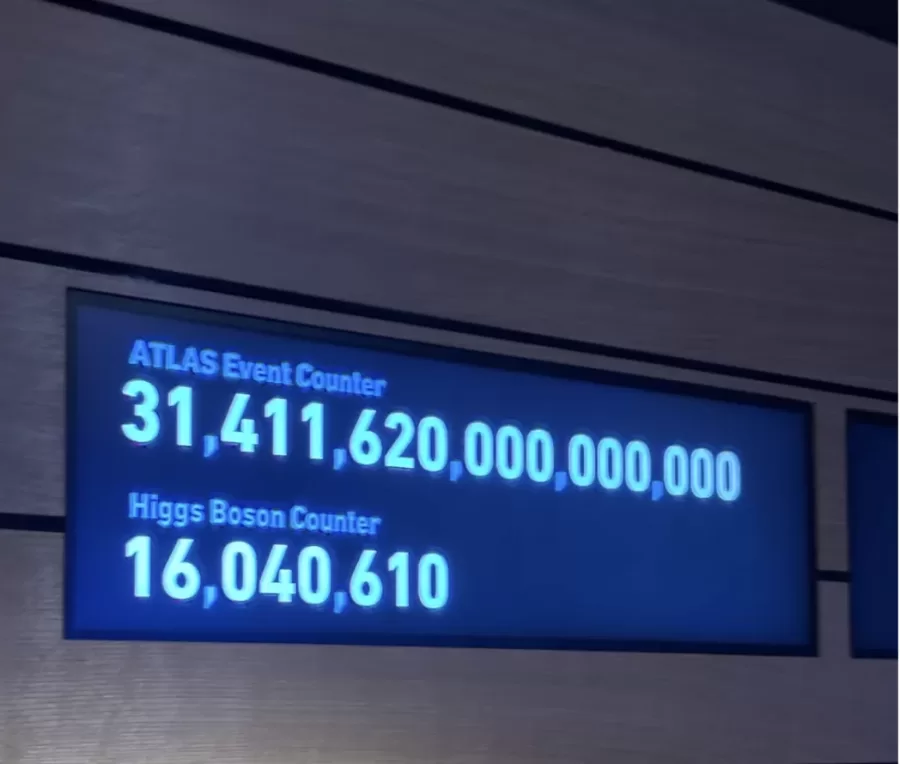

Fermilab and CERN have been leaders in scientific discovery for years. In 2012, the Higgs Boson elementary particle was verified, and this helped solidify the Standard Model of Particles. This model starts to unify three of the four fundamental forces in the universe. Today, Fermilab focuses on neutrinos, while CERN conducts high-energy particle collisions to learn about the makeup of matter. They continue to expand our knowledge of gluons, muons, and quarks.

If you do not understand the last paragraph, you are not alone. I am a high school science teacher with over 30 years of experience, and I did not understand much of this paragraph. This troubled me. Science teachers try to keep up with current events. Phenomena such as ozone holes, global climate change, PFAS, and COVID have influenced the topics and logistics of teaching high school science. However, the scientific endeavors going on at Fermilab and CERN were mysterious to me. The Barlow Educator Grant allowed me to visit these facilities to expand my own understanding and create some virtual materials to expose my students to some of the newest science advancements available.

Trip Report

The first stop on this grand adventure was Fermilab located in Batavia Illinois, about an hour’s drive from Chicago. It boasts some of the world’s largest particle physics equipment.

Utilizing high-energy particle accelerators, Fermilab has discovered Bottom and Top Quarks, the Tao Neutrino. In addition, Fermilab was an important contributor to CERN’s work in finding the Higgs Boson (this is the particle that some in the media named “The God Particle”). Fermilab’s largest accelerator was called the Tevatron. It was 4 miles in circumference and was in operation for almost 30 years. In deference to the work being done with the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, Fermilab has closed the Tevatron down and is now focused on expanding our understanding of Neutrinos.

Fermilab also prides itself on its work on reconstructing the prairie ecosystem. It has thousands of acres of natural grasses and even hosts a Bison Herd.

I attended a three-day workshop for high school physics teachers on-site at Fermilab. The goal of this class was to provide teachers with methods of bringing some of the newest particle physics discoveries into a high school classroom and strategies to make it understandable. This was perfect for the purposes of this grant. It started with some math review that led into a whole explanation of how high-energy accelerators “discover” new particles. These new particles are around for such a short time that the scientists do not search for the actual particles, but their decaying pieces. First-year physics students study conservation of momentum and conservation of energy equations. Detectors collect all of the possible pieces they can after a collision. Using conservation of momentum and conservation of energy, they can start to piece together where these particles originated. Billions of collisions later, the data starts to show the discovered particles with high certainty. Although very complicated, it can be simplified for high school students.

The three-day workshop also provided the opportunity to hear from two scientists who work at Fermilab. Pedro Machado is a theoretical physicist, and Don Lincoln is an experimental physicist. These scientists shared different perspectives on the activities at Fermilab and CERN. To oversimplify, the theorist looks at the data and tries to put it together and formulate the next steps. The experimentalist collects the data and tries to prove or disprove the theorist’s hypothesis.

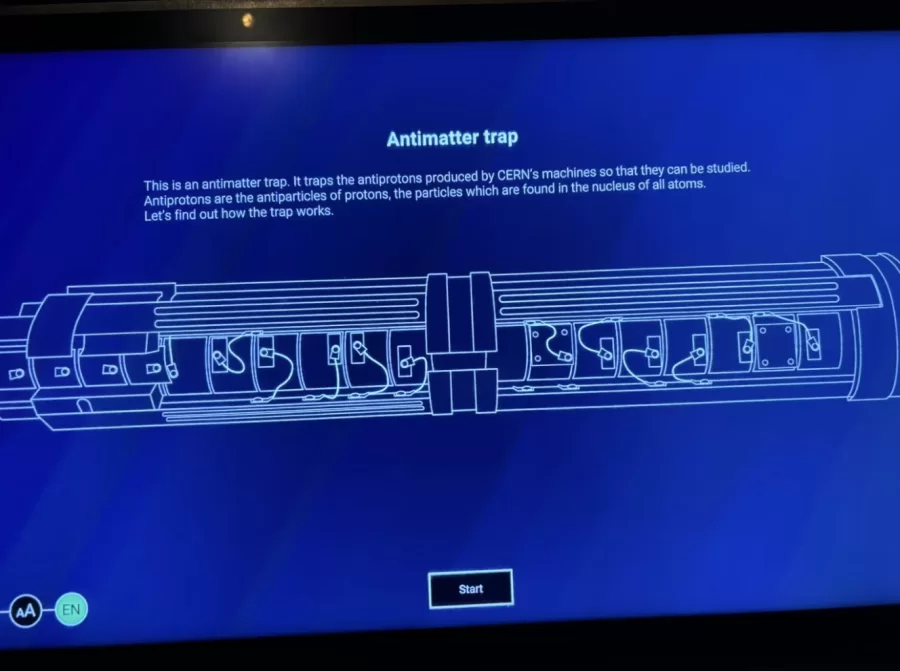

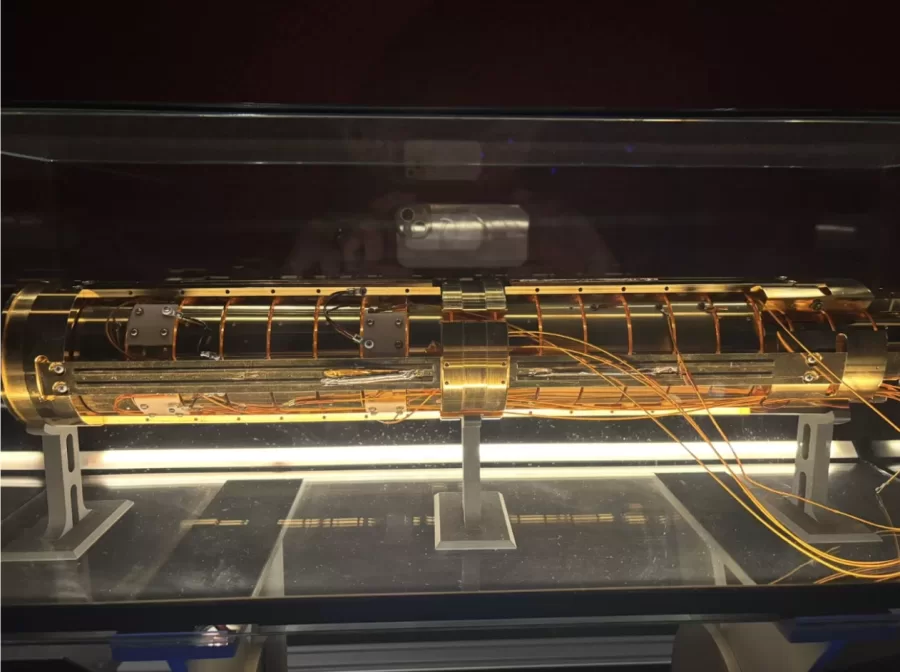

Touring Fermilab was also very eye-opening. Highlights included the Lederman Science Center, the bison herd, and Wilson Hall (the central laboratory building). Although close-up viewing of equipment and colliders was not allowed, there were many opportunities to get glimpses into what Fermilab is doing. I was lucky enough to see a lot of the old equipment used in the Tevatron and look directly at the 4-mile Tevatron loop. Particles did not simply enter the Tevatron loop. There is a series of loops that accelerate them before they enter the actual Tevatron loop. I was able to see many of these “warm-up” loops. Lastly, I saw the building where they made the antiprotons used in some of the collisions.

The fourth day at Fermilab was one of the most special as I was joined by my wife, two children, and father-in-law. My wife (Cathy Squires ’88) grew up just north of Chicago. Her father (90 years old) has lived an hour from Fermilab for many years, but never visited. We were able to make this bucket list item come to fruition. With a lot of help from the connections I made during the conference, we were able to show my father-in-law many of the highlights at Fermilab. It is such a great memory, and I was thrilled to have my family see how I spent the previous three days.

CERN – Geneva, Switzerland

We flew from Chicago to Zurich and took a high-speed train to Geneva. It made for a long travel day, but well worth it. I spent two days at CERN, and while my time there was shorter than my time at Fermilab, it was even more eye-opening. CERN is a world-class science facility with an amazing history of international cooperation.

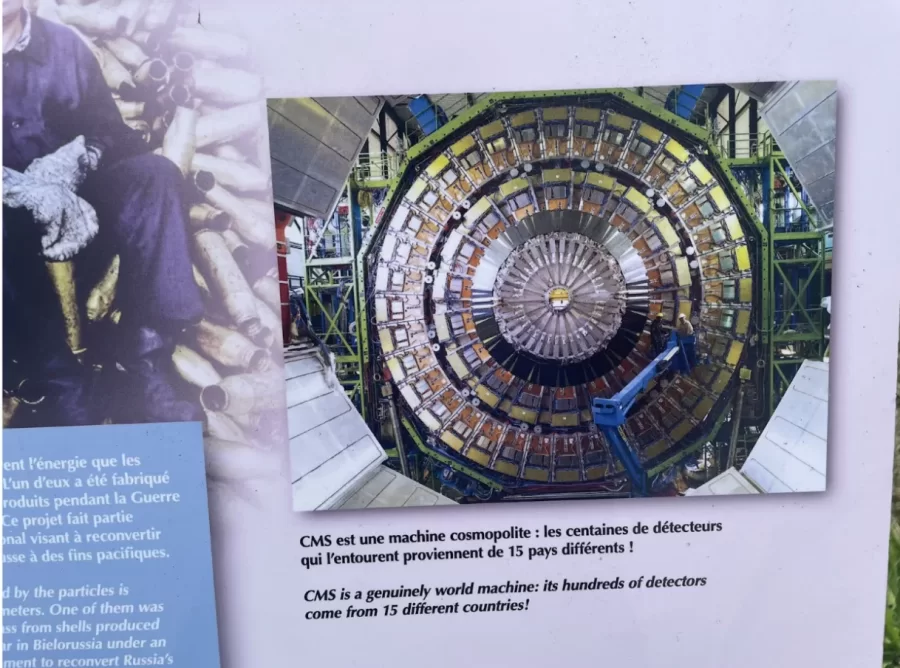

In the aftermath of World War II, much of the science community was located in the US and had been focused on scientific advances for militaristic purposes. (You can watch Oppenheimer for more about this). European Scientists wanted to build a premier facility that was solely based on scientific advancement, not for the military. Twelve countries signed on in the mid-1950s and CERN was created. Each member country contributes a certain amount of its GDP, and CERN staffing is then based on that contribution, so all member countries directly participate in terms of job opportunities and exposure to scientific research. While the US is not a member, it has “observer status,” which enables Fermilab to work closely with CERN. Discoveries made at CERN led to many life-changing technologies, such as medical imaging, cancer treatments, and the World Wide Web. The Large Hadron Collider is the crown jewel of CERN.

Visiting CERN is incredible. When you enter, there is a large area of interactive displays, visuals, and even artwork in various forms inspired by science. CERN draws big crowds, and getting a spot on a tour is difficult and managed on a first-come, first-served basis. Two hours before every tour, they open the online portal for tour registration, and the first 16 are welcomed on the tour. During the two-hour wait, we walked around the exhibits and saw a video of the history of CERN and a live science show about matter. The show gave me quite a few ideas for my classroom.

The tour was incredible. Our tour guide, a post-graduate physicist, worked at one of the two main detectors, the ATLAS detector. The first stop was a room-sized accelerator called a Cyclotron. This was CERN’s first accelerator. Along the wall were pictures of the early scientists who worked on this machine. The tour also covered CERN’s history, the member nations, and how work is equitably distributed among the member nations. The last stop on the tour was the ATLAS building. A mural of the ATLAS is drawn on the building, although the detector itself and the entire Large Hadron Collider are deep underground. Our guide brought us into the ATLAS building and proceeded to give us a series of talks and video clips that brought the entire two-continent experience into perspective. I videoed his talk, and it will be the grand finale to my virtual field trip to be shared with my classes. He then took us to see the working control room, which was amazing. The next day I returned and made sure to take pictures and videos of the displays so my students could get a full picture of CERN.

I had a bonus realization that put the size of the Large Hadron Collider in perspective. The circumference of the LHC is seventeen miles. That is easy to say, but understanding how big it really is took a stroke of luck. Our Airbnb was located in Cessy, France, and it was a twenty-minute drive to CERN. In reviewing a map that depicted the location of the LHC, I realized that our Airbnb was only 300 meters away from the second major detector, the CMS. This structure looked like a large factory. I visited the building and was able to get more information about the size and structure of this detector.

Reflections and Next Steps

This trip was about science, of course. But it also has its tentacles in geography, economics, history, philosophy, and political science. From the outset, I knew I would be in awe of the scientific achievements on display at Fermilab and CERN. That was certainly the case, but the bigger inspiration is the clarity the trip brought to the fact that science is not just about uncovering quantifiable facts; it is about human inquisitiveness and discovery, achievable only through collaboration at many levels (intellectual, political, and economic). It is the pursuit of knowledge, the reaching into the unknown without even fully understanding the end goal. It is about adapting, adjusting, and recalibrating; in a word, it is about learning. The discrete discoveries, such as neutrinos, muons, and quarks, are fascinating. Still, the true source of the awe is in the combination of infinite curiosity, imagination, and collaboration that are fundamental to human experience.

I appreciate the opportunities that Bates and the Barlow grant have provided me and feel strongly that a liberal arts education is the basis for lifelong inquisitive pursuits and openness to continued learning, not just of facts, but where they fit into humanity’s journey. More than anything, this is what I hope to impart to the students in my science classroom.